The monkeypox virus is on the rise in Belgium, but a lot of misinformation about what it is and how it is spread is still circulating online. Here is an update of everything we know about the virus now.

Since the start of the outbreak, 546 confirmed cases of monkeypox have been registered in Belgium, according to the latest figures by the Sciensano National Health Institute.

As of this week, the number of new infections appears to be reaching its peak, although the coming weeks will have to show whether there is a stagnation or a decline, said virologist Boudewijn Catry during a press conference on Wednesday.

What is the monkeypox virus and how does it spread?

The monkeypox virus is an infection that is transmitted from animals to humans. The name, however, is slightly misleading: while monkeypox was first identified in monkeys, rodents can also transmit the virus.

Infected people first get a fever, chills, muscle aches and fatigue. After one to three days, spots start appearing, which turn into blisters. The fluid in these blisters is infectious.

The best-known way that the virus spreads is through skin-to-skin contact: it must come into contact with a wound, virologist Johan Neyts (KU Leuven) told De Morgen. However, it can also enter through mucous membranes, such as the genitals and the mouth.

Additionally, monkeypox is not related to chicken pox. "Those viruses belong to two completely different families. That is like comparing a head of lettuce to a chestnut tree," said Neyts.

Can the virus only be spread through the skin?

No, but the most important thing to keep in mind is that monkeypox does not spread easily between people without close contact.

The fluid from the blisters is highly contagious, and if it ends up on materials, it can remain contagious for at least five days, said Neyts. The virus lingers longer on bedding, towels and clothing than on materials such as plastic, metal and glass. However, wound fluid in textiles is easy to remove in the washing machine (at the highest possible temperature).

In recent weeks, concerns were raised about the transmission of the virus through second-hand store clothes following an advisory letter that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has since dismissed as "fake."

Neyts, too, stressed that it is nearly impossible to get infected with monkeypox through clothing, but added that there is a possibility of getting infected by sleeping in sheets that were previously slept in by an infected person.

Touching infected surfaces does not seem to be an effective way of getting infected so far, because the virus would spread more rapidly if this were the case.

Should you be worried if someone close to you is infected?

Not necessarily, but caution is always advised. The main high-risk contacts are sexual partners. Other high-risk contacts are people living in the same household or who have been on holiday with someone who is infected.

Healthcare workers who have had unprotected contact with an infected person are also at increased risk. Other social contacts, such as colleagues or people at the gym, for example, are at very low risk.

Monkeypox usually heals spontaneously after two to four weeks. Until then, it is advised to stay in isolation. The rash changes from a pimple to a blister, until eventually a scab forms. When the rash is completely healed (meaning the wounds have dried and a new layer of skin has formed), you are no longer infectious.

Is the monkeypox virus an STD?

While the monkeypox virus is not a sexually transmitted disease (STD), it can be transmitted during sex because it is spread through skin-to-skin contact and through the mucous membranes. Cuddling can also be enough to transmit the virus.

Are men more likely to be infected?

No, it is not true that men or women are more or less likely to be infected, said Neyts: it is about close contact. If an infected man has skin-to-skin contact with a woman, she also has a chance of being infected, and vice versa.

So far, however, monkeypox is mainly found in men who have sex with men who frequently have sex with different partners. Earlier this week, the first infection in a woman was detected in Belgium.

In principle, everyone is at risk of getting monkeypox, including children. In Belgium, no children have been infected with the virus yet.

How can the virus be stopped?

The principle is easy: by making sure the virus does not get a chance to spread. This is done by avoiding contact with an infected person and through vaccination, said Neyts.

As the risk to the general population is currently estimated to be low, there will be no nationwide vaccination campaign like with Covid-19 and only risk groups will be vaccinated.

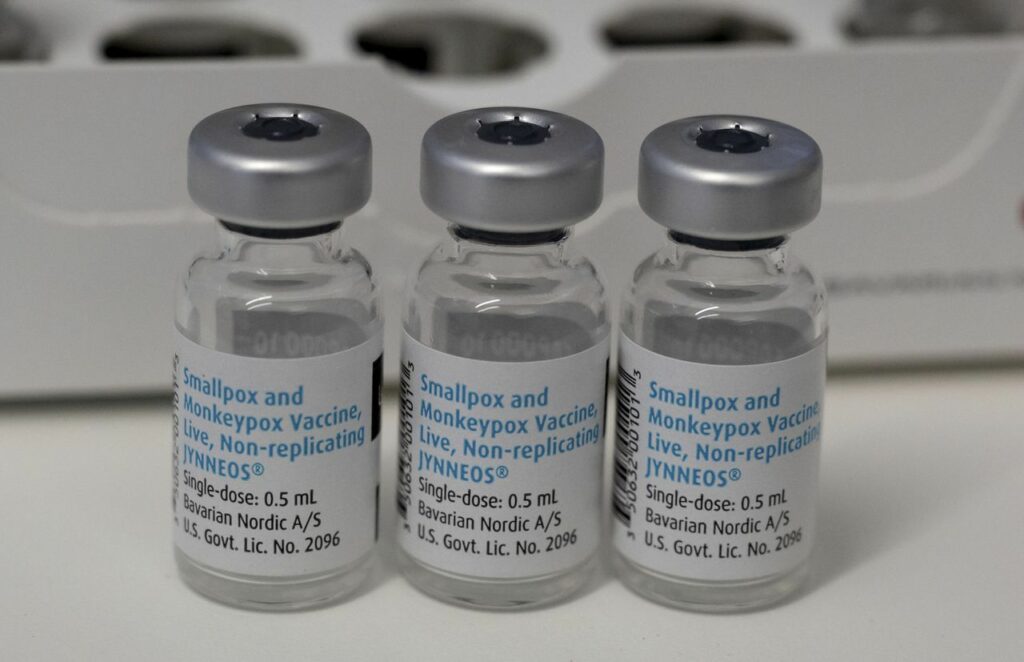

Currently, Belgium has a very limited stock of vaccines and is using available doses for preventive vaccination of risk groups, aiming to vaccinate the target groups "by the end of next week at the latest," Federal Health Minister Frank Vandenbroucke told VRT.

Still, he added that this will likely not be "entirely successful," as some people in the target group are difficult to reach. Others, however, crossed the border last weekend to get vaccinated in France.

Who is eligible for vaccination?

In addition to high-risk contacts, the Belgian authorities will only administer preventive vaccination to specific groups of people, the biggest of which consists of men who have sex with men and are HIV-positive or taking PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) and have contracted at least two sexually transmitted infections in the last year.

Other eligible groups are male and transgender sex workers, people with severe immune disorders – including uncontrolled HIV infection, immunosuppressed responses to medication (such as after transplantation), malignant blood diseases, congenital immune deficiencies, etc – and a high risk of infection, and laboratory staff handling virus cultures.

Related News

- Help centre and raising awareness: Flanders steps up monkeypox information campaign

- 'Too litte, too late': Brussels hospital receives 100 monkeypox vaccines

- First female monkeypox patient diagnosed in Belgium

Currently, an estimated 300 to 400 people living in Belgium have been vaccinated since the outbreak of monkeypox, said Vandenbroucke. "At the start of the epidemic, we were able to buy 200 doses. Through the European Commission, we were able to get another 3,000."

Meanwhile, another 30,000 doses have been ordered from producer Bavarian Nordic, reiterated Vandenbroucke. "They will be delivered in the fourth quarter (autumn) of this year."

While a full vaccination schedule normally means two doses, administered 28 days apart, Neyts said that the built-up immunity after one dose should be sufficient for the time being. The second dose can wait until later this year or 2023, when the production of the vaccine has caught up.

Can Belgium not use the traditional smallpox vaccines?

No. In very extreme and deadly situations, the second-generation smallpox vaccine that Belgium has would be suitable against the virus, but in the case of monkeypox, the third-generation smallpox vaccine is the only one that can be used widely.

"The traditional vaccines cannot be used against monkeypox because the side effects are very serious," said Vandenbroucke. "You can use the vaccines with serious side effects against a deadly disease, such as traditional smallpox. But not against monkeypox because it is not lethal."

The Netherlands is in a much better position, as it is among the few European countries that have replaced their older smallpox vaccines (those of the second generation) with the latest third-generation ones two years ago.

Any more questions?

Those who have questions or want more general information about the virus can call the recently opened 1700 info line on weekdays from 09:00 to 19:00.

This weekend, when the Antwerp Pride is taking place, the info line is also open, as the Flemish expertise centre for sexual health Sensoa has noticed a growing concern about the monkeypox virus within the LGBTQ+ community.

"In this phase, there is absolutely no reason to panic, there is no risk of transmission by for example celebrating together," said Flemish Health Minister Hilde Crevits.