Here in Brussels in 2017, we live in a wonderfully peaceful, violence-free time and place. With terrorism filling the front pages of our newspapers and the initial minutes of the evening news, with armed soldiers decorating our streets and security guards searching our bags, you may think I am joking. But I am not. To get a useful sense of perspective and realize how fortunate we actually are, just read The Better Angels of Our Nature, Harvard Professor Steven Pinker’s well documented account of the secular decline of violence and insightful analysis of its causes. Or reflect on the following tragic anecdote, illustrative of the sort of violence that prevailed right here not so long ago.

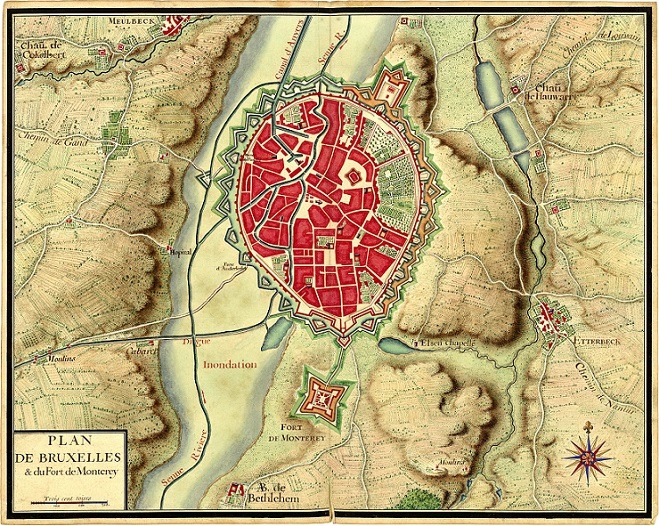

We are at the beginning of the 18th century. The king of France and the emperor of Austria keep quarrelling. The conflict between them has already caused the bombing of Brussels in 1695 and the total destruction of the city’s medieval Grand Place by marshal de Villeroy. The quarrel is now focusing on who is to become king of Spain: the grandson of the French king Louis XIV or the son of the Austrian emperor Leopold I of Habsburg. And as the interests of other countries are involved, the conflict spreads, with England and Holland siding with the emperor.

An English army is sent to the Spanish Low Countries (corresponding roughly to present-day Belgium since the secession of the Netherlands at the end of the 16th century), under the command of John Churchill, duke of Marlborough, the subject of the popular French song “Malbrouc s’en va-t-en guerre” and ancestor of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. On 23 May 1706, it meets the French army led by Villeroy in Ramillies, about 40 km south-east of Brussels. Marlborough wins the battle, enters Brussels a few days later and appoints his brother Charles Churchill governor of the city.

John Churchill, the duke of Marlborough: In 1706, An English army is sent to the Spanish Low Countries (corresponding roughly to present-day Belgium since the secession of the Netherlands at the end of the 16th century), under the command of John Churchill. On 23 May 1706, it meets the French army led by Villeroy in Ramillies, about 40 km south-east of Brussels. Marlborough wins the battle, enters Brussels a few days later and appoints his brother Charles Churchill governor of the city.

The king of France and his coalition do not give up. In November 1708, another army is sent to reconquer Brussels, under the command of Archduke Maximilian-Emanuel, prince elector of Bavaria, former governor of the Spanish Low Countries on behalf of the emperor, but now on the side of the king of France. The man charged with organising the defence of the city is called François de Pascale. The garrison under his command gets the support of militias of Brussels citizens, led by a certain Pierre van den Putte.

The battle rages throughout the night of 26 to 27 November 1708. Maximilian-Emanuel puts his headquarters in one of the few buildings outside Brussels’ fortifications (today’s inner ring) to the east of the Louvain Gate (today’s Place Madou): the “Hof van Toulouse”, located next to what is still called today, for this reason, the rue de Toulouse. In the 16th century, this was the country house of Jacques de Marnix de Toulouse and his son Philippe de Marnix de Sainte Aldegonde, chief adviser of William the Silent, prince of Orange-Nassau and founder of the Dutch nation.

From this position, Maximilian-Emanuel’s canons fire shells all the way to the city centre and manage to destroy the Blue Tower, located on the fortifications between the present locations of the American Embassy (rue Zinner) and of the residence of Belgium’s federal Prime Minister (rue Lambermont). At about 9 am on 27 November, de Pascale succeeds in driving away Maximilian-Emanuel’s army. According to his report, three thousand men were killed among the assailants, and three hundred among the besieged.

To celebrate the victory, Brussels’ governor Charles Churchill organises a banquet and to express his gratitude to the citizens of Brussels, he sends to the wife of Pierre van den Putte a pan filled with fruit and jam. As for François de Pascale, he is made a marquis the following year by the future emperor Charles VI of Habsburg, still hoping at the time to become king of Spain. De Pascale could not have suspected that at the end of the following century, his name would be given to a street crossing the fields that he proudly helped turn into a graveyard.

Rue de Pascale, overlooking the European Commission. The street is named after François de Pascale, the man charged with organising the defence of the city in 1708 against Archduke Maximilian-Emanuel. The garrison under his command got the support of militias of Brussels citizens. At about 9 am on 27 November 1708, following a bloody battle with thousands of casualties, de Pascale succeeded in driving away Maximilian-Emanuel’s army.

Three centuries later, Bavarians and Brits, Austrians and French, Spaniards and Dutch are living peacefully side by side in the rue de Pascale and the rue de Toulouse, and in many other streets of Brussels’ European Quarter. The German Land of Bavaria has even established its sumptuous representation to the European Union just a few hundred meters from the place from which the prince elector of Bavaria bombarded Brussels. By way of celebration of the tercentenary in November 2008, one might have thought of re-enacting the battle, in Waterloo style, with local residents from the various countries involved. Or perhaps the Land of Bavaria could have hosted a banquet in its mansion, or offered a pan filled with fruit and jam to the inhabitants of the rue de Pascale.

For such celebrations, it is now too late. But it is not too late to ponder for a while on these thousands of Europeans whose blood sunk into the soil that now hosts the main institutions of a united Europe, or indeed on the far more massive mutual killings that happened less than a century ago.

The fact that such massacres happening again has become so hard to imagine today is not the result of any change in the DNA of European males or of the eradication of their biological propensity to fight and kill. It is the result of the laborious development of smart institutions of an unprecedented kind that have helped tame sufficiently — so far — one of the worst angels of our human nature: nationalistic passion.

One component of this taming process is the daily interaction of people from all over Europe living, talking and working together in a neighbourhood in which people from much of Europe spent a long night slaughtering one another, over three centuries ago.

By Philippe Van Parijs