Brussels does not enjoy the reputation of being a leafy and airy city. Its traffic jams are legendary. Yet just a kilometre walk from its urban core, marked by the stone box that is the Grand Place, passers-by begin to glimpse a blur of green through the front windows.

This is the ring of 19th century suburbs, where tiny back gardens are preserved behind terraced houses. A second belt of 20th century detached and semi-detached villas and apartment blocks with communal gardens follows.

Along the tidemark between these two waves of expansion are large parks, remnants of the ancient meadows and forests of Brabant, linked by planted boulevards. These private and public reserves of greenery are the legacy of a century of planning that aimed to use the power of plants to soften the hard edges of metropolitan life. They represent a search for the picturesque that began with the redevelopment of the medieval downtown in the 1860s and halted by the embrace of the automobile amid the consumer revolution of the 1950s.

A surprising number of these private and public gardens were the work of a single landscape architect, Jules Buyssens, whose long career began halfway through that period. Picturesque, an exhibition at CIVA, the Brussels region’s modern architecture museum, shines a light on the little-known campaigner and businessman. Generator of almost a thousand projects across Belgium, it was in Brussels where Buyssens used his public position as head of the city’s park system to promote his private vision for a new national garden aesthetic.

When it became the capital of the new state of Belgium in the 1830s, public space in the historic centre of Brussels still meant the street. Large convent gardens, taking up huge swathes of the city, had always existed behind high walls, but when the abbeys and monasteries were dissolved, the land passed into private ownership for industrial use or home building. Aristocratic residents of the upper town had access to a new Royal Park. However, for the vast majority of the population in the lower town, squeezed between its medieval walls, the backdrop to daily life was ancient, grimy walls and narrow lanes.

The inhabitants of Brussels needed breathing space and inevitably, the wealthy were served first. By the late 1830s, the first purpose-built suburb, the Quartier Léopold (now known as the EU Quarter) was laid out by a private company promising the ‘beautification’ of the city. An eastwards extension of the neoclassical upper town that reached beyond the city wall, its residents (and shareholders) were the aristocracy and Belgium’s new plutocrats, who would fill a strict grid pattern with austere mini-palaces that turned streets into stone corridors.

Belgium’s first suburb

As early as the 1850s, attempts were made to soften its hard edges. Trees and lawns were planted in its two large squares and a zoological garden (now Leopold Park) was added at the fringe of the quarter. As a prototype, the Quartier Léopold had shown that a successful modern suburb would need to address the public as consumers of a planned streetscape. This could perhaps be achieved through an alliance between the mason and the gardener to achieve a new concept, the urban picturesque.

A further extension of the city of Brussels was planned, towards the end of the 19th century, to the northeast of the Quartier Léopold. The planners were determined to avoid the mistakes of its flinty, perpendicular predecessor. Key to this was a blurring of the right angle using greenery and an innovative street pattern, which made a virtue of the uneven terrain (approached from central Brussels, the streets splayed out like the fronds of a fern).

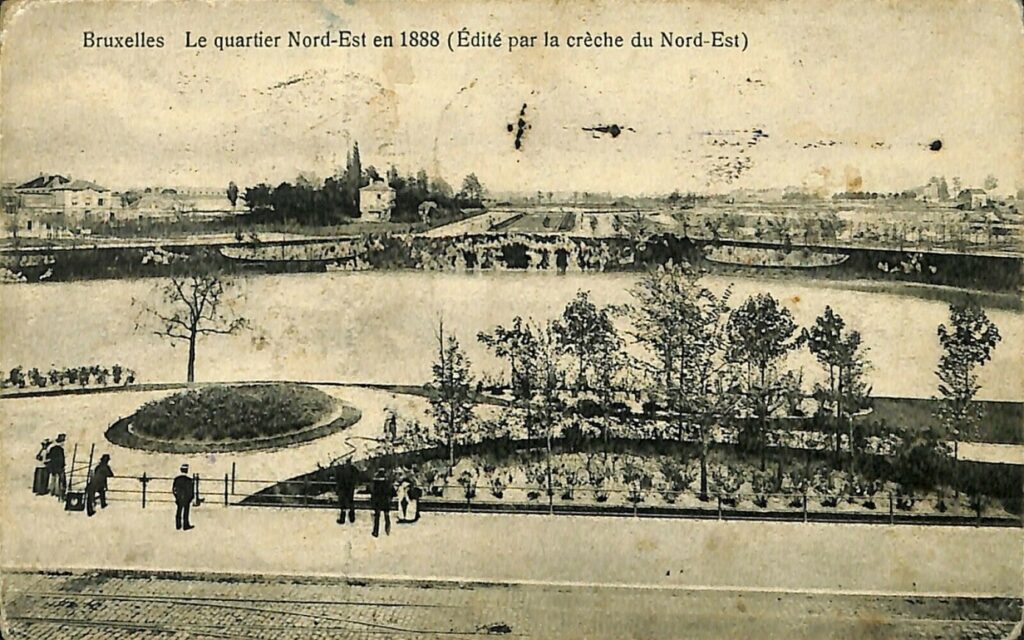

The North-East quarter in 1888

At the heart of this new North East Quarter were four ‘squares’ (only one of which was rectangular). Set on a slope, Squares Marguerite and Ambiorix and avenue Palmerston were each filled with green spaces leading downhill, widening, narrowing and widening once again at square Marie Louise, surrounding a broad pond formed from the sluggish stream of the Maelbeek.

To further avoid the risk of monotony, the scheme’s designer Gédéon Bordiau insisted on an ordinance requiring facades to be set back five metres to allow for gardens, protected by railings in front of each house built in the square. In this way, he said, a nonstop cascade of flowers and bushes, would give “an artistic and picturesque appearance of absolute necessity.”

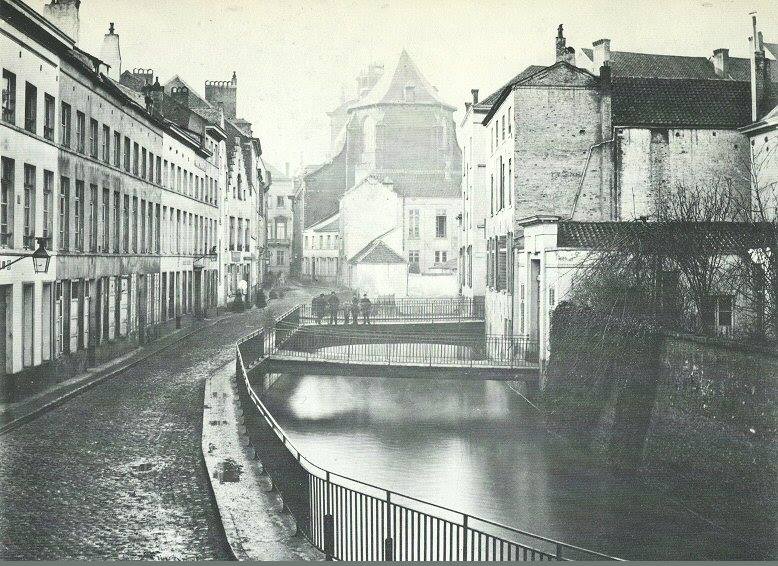

An ancient city preserving its medieval street pattern might be picturesque to 21st century eyes but to Brusseleirs at the outset of Leopold II’s reign, it meant squalor. As the historic core embarked upon a century-long period of demolition and upheaval, those who could afford it headed to the northeast and other areas in the solidly middle-class belt of suburban growth.

Rue de la Fiancée, next to the river Senne that flowed through Brussels, behind Place de Brouckère, 1867

They were in search of peace and privacy but also foliage. As the writer Camille Lemonnier put it: “With the city being steam cooked in its tangle of dead ends and alleys, the modest fortunes, the clerks, the bourgeoisie, lured by the attractions of gardening made their exit.” Many of these people would thrive in the final years of Leopold II’s reign as the proceeds of the Congo empire flooded in, and they were the ideal market for a reinvented mode of city living focused on the picturesque.

Parisian landscape vs English ‘wild garden’

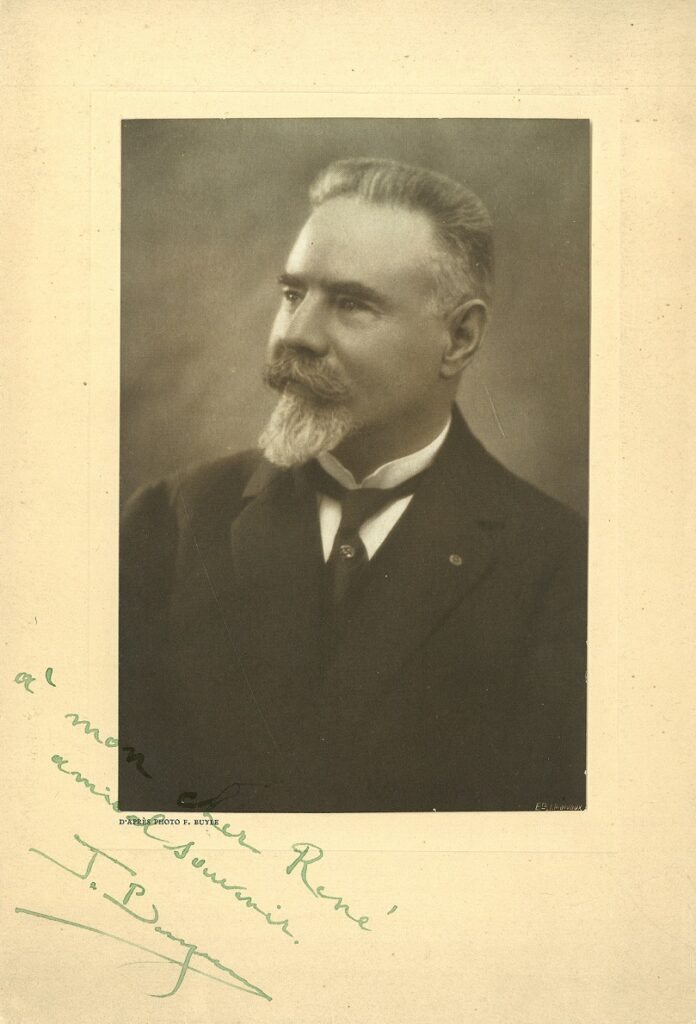

In 1904, Jules Buyssens set up his office at the edge of the new North East Quarter, on the corner of the street that bears Bordiau’s name. He was young landscape architect just back home after more than a decade of work experience across Europe. Born in 1872 (his 150th anniversary is the reason for the exhibition), Buyssens had just been named Inspector of Brussels parks. The exhibition at CIVA explores his determination to write the next chapter of Belgian garden design.

Jules Buyssens

Buyssens had won the post of city parks inspector thanks largely to his experience of foreign gardening technology and to the recommendation of his mentor and employer over the previous decade, the Parisian landscape architect, Édouard André. André had combined a public sector career under Baron Haussmann’s head of parks, Adolphe Alphand, with lucrative side projects, such as transforming the country estates of the Belle Époque aristocracy.

Buyssens followed suit, directing his team of more than 60, maintaining the parks, boulevards, cemeteries and other planted areas of the Brussels City, while snapping up many of the finest patrician gigs available during the final years of excess leading up to the First World War. In 1912, for example, he was awarded a project to transform the Ronchinne estate for King Leopold II’s daughter Clementine and her husband Victor Napoléon. A framed photo of the princess she sent to Buyssens appears in the exhibition alongside a newspaper clipping kept by him announcing her death.

The Ronchinne estate

This well-connected civil servant teamed up with other landscapers, artists and botanists to start a magazine to promote garden design. Le Nouveau Jardin Pittoresque (New Picturesque Garden) launched in 1913, describing itself as the journal for “a national association for the renovation and the popularisation of garden art”.

The NJP was sharply critical of garden design in Belgium, calling for an end to the French influence, which under Alphand and André had reached a point where aristocratic country estates and municipal parks had come to resemble each other in their bloated finery (“a cream cake surrounded by macaroons”, as an NJP board member put it).

Buyssens picked up instead on the English ‘wild garden’ fashion that emerged in the 1870s, an offshoot of the arts and crafts movement that sought to restore a perceived lack of vernacular input in visual creation. The NJP carried translations from British garden magazines and this influence is reflected in the English title of the exhibition.

Its philosophy squarely rejected the geometric, ‘artificial’ designs championed by a rival, André Véra. The name of the magazine itself was a reaction to Véra’s 1912 book Le Nouveau Jardin. For the NJP, the content of a garden was as important as its design and this should take its lead from nature. Instead of annual planting, local varieties and exotics, graded by colour and sufficiently hardy to thrive in the Belgian climate, should make up the gardener’s palette.

As befits a philosophy germinated in late Victorian salons, paternalism had its place in the potpourri of ideas that accompanied the launch of the NJP. In 1914, it promised a series of articles on workers’ gardens and the link between “the evolution of the garden and that of morals”.

However, publication was halted during the First World War, and for almost a decade, architects and planners set their minds to anticipating the opportunities of a world where a new division of wealth and a change in politics meant many of the old certainties no longer existed.

By the time the next issue of NJP came out in 1923, as the Brussels building industry began its recovery, those founding members most attached to its social aims had departed. The most prominent among these, Louis Van der Swaelmen (whom Buyssens had beaten for the post of inspector) threw himself into the garden city movement, which treated planting and architecture as an integrated and communal system for providing decent, affordable housing for workers.

The business of greenery

For Buyssens, the relaunch was the cue to consolidate the magazine as the face of a vertically integrated business promoting his services as a landscaper serving the middle classes. As suburbia surged into the farmland surrounding Brussels, plots grew larger and wider. The traditional terraced house unfolded into detached and semi-detached villas no longer subject to strict building lines.

With the division of public space between wheeled vehicles and pedestrians formalised in the 1920s, it was the roadway and pavement that came to define the line of the street. Houses meanwhile retreated towards the centre of their plots and the garden increasingly usurped the role of the façade as the expression of the middle-class home. With aristocratic country estates ruined by WW1, it was middle-class clients who would sustain Buyssens the businessman and become the focus of his magazine.

Buyssens owned a large nursery at Fort Jaco in Uccle, an area only semi-urbanised and which would become ground zero for the Brussels villa set in generous grounds. In 1924, the business was expanded to take in landscape design studios, sheds for his large team of gardeners and a home for the full-time caretaker.

Here, he experimented with new varieties and maintained a large stock of plants to supply both his public and private projects. Weekly gardening masterclasses were open to the public and marketed through the magazine.

Le Nouveau Jardin Pittoresque organised field trips to gardens both in Belgium and abroad and held an annual exhibition. Lectures on plants were illustrated by autochrome slides, helping potential clients visualise the impact of the colour combinations of plants and flowers promoted by the association. These activities drove a steady stream of orders, some for very small sites. Buyssens provided planted terraces, for example, to sit atop the garages appearing in the squeezed back gardens of early adopters of the car.

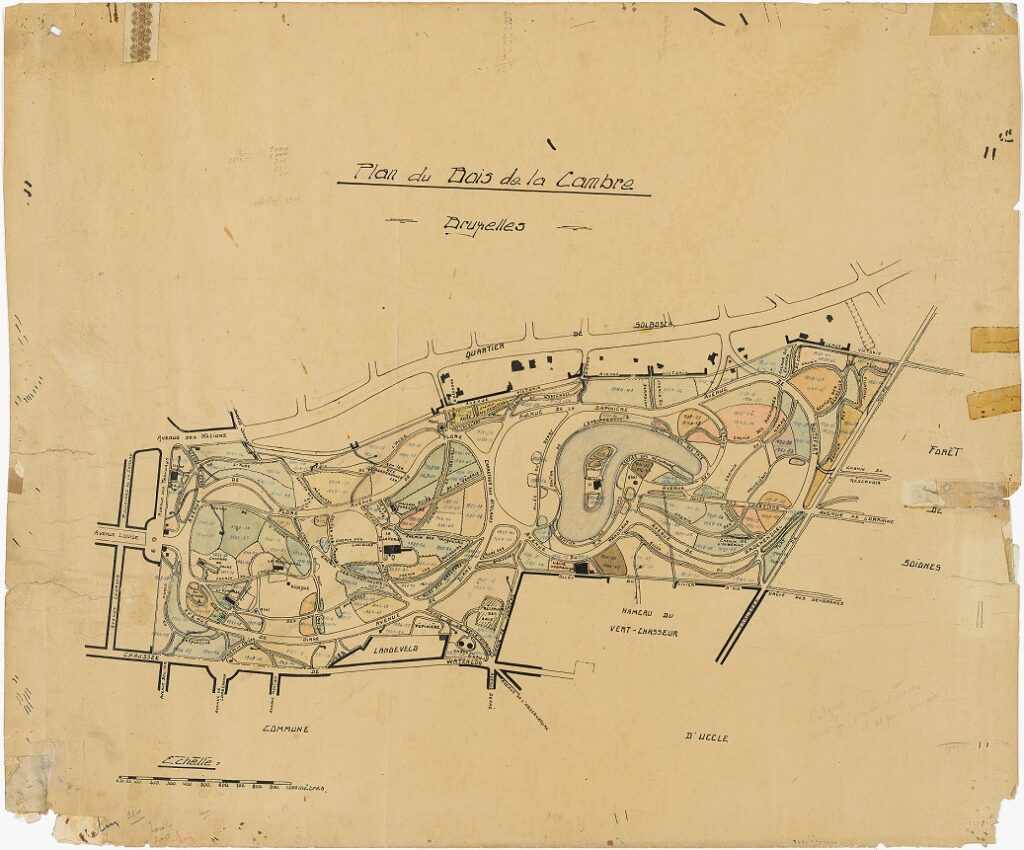

Abbaye de la Cambre plans

At the same time, Buyssens’ training in the pre-war world of vast aristocratic estates meant he was able to take on major challenges, such as the recreation of the historic gardens of the Abbaye de la Cambre in Ixelles and mid-sized private projects such as the garden of the van Buuren banking family’s art-deco villa in Uccle. The plans and contemporary photographs of such sites are the most striking items on display at the Picturesque exhibition at CIVA.

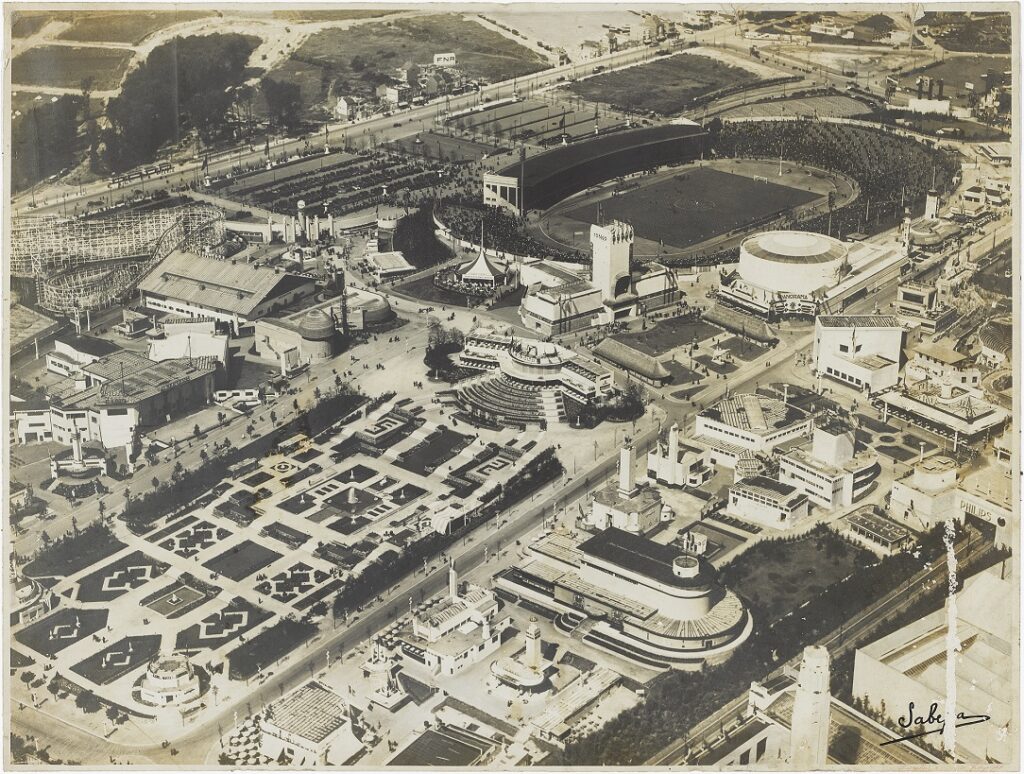

The culmination of Buyssens’ career arrived with the Brussels International Exposition of 1935, where he designed the grounds around the pavilions and directed a team of 130 workers over two years to transform an abandoned quarry into the new Osseghem Park. This included the creation of a 540-metre-long pond and an open-air theatre inserted within a curved landscape crowned by trees planted for the project. To underline the chromatic variation advanced by Le Nouveau Jardin Pittoresque, coloured lanterns illuminated their leaves at night.

21st century urban picturesque

Part biography of a Brussels businessman with a talent for self-promotion, part narrative of a new aesthetic movement that perhaps never was, the Picturesque exhibition does offer particular conclusions on the impact of Buyssens on posterity. You explore the exhibition as you might one of the many large and colourful gardens whose plans hang on its walls.

As Inspector of Brussels parks from 1904-1937, Buyssens had decades in which to root out artificiality and strengthen the place of greenery in the city. His period in charge however was followed by the rise of the endearingly unfashionable flower clock at the entrance to municipal parks. The year of his death, 1958, saw the triumph of the tunnels and urban freeways that eliminated the trees along the boulevards of Brussels, ending their century-old role as colour-coded vestibules leading to the park system and painting the city grey for the decades to come.

Aerial view of the 1935 Universal Exhibition grounds in Heyzel

Perhaps a more substantial legacy can be salvaged from the strong link between the Le Nouveau Jardin Pittoresque and the botanists of a century ago who were the first to explore sustainable biodiversity in the city.

In 1922, along with university professor and fellow NJP board member Jean Massart, Buyssens created the experimental botanical garden in Auderghem that bears Massart’s name. It aimed to represent the breadth of plant life, either indigenous to Belgium or able to thrive productively in its climate. Gardens and squares across the Brussels region are currently being replanted or created using such an approach.

Not without controversy, planners are using greenery as a tool to reverse the domination of the car. Since 2016, a new green corridor has been snaking its way through the rundown northern fringe of downtown Brussels, progressively restoring the course of the city’s vanished river as a natural site.

The public environment agency in charge of Buyssens’ former duties described the Senne Park thus: “The plants have been chosen to offer a colourful landscape all year round. Priority has been given to biodiversity in this dense urban area. The vegetation is indigenous and exotic.” This 21st century vision of a new Belgian urban picturesque perhaps owes some debt to the philosophy of Le Nouveau Jardin Pittoresque. The theorist in Buyssens would have approved and the businessman would have been delighted to supply the goods.