If, like many, you thought it was impossible for someone who isn’t Chinese to become a Mandarin, you’d be wrong – and Belgian Paul Splingaerd is evidence, albeit isolated, of that. No one knew how Splingaerd, who was an orphan, became a Mandarin in 19th century China. That is, until now.

Fascinating new research by his great granddaughter Anne Megawan Splingaerd sheds light on the life of Splingaerd, an intriguing figure and, surely, one of the few whose own personal history straddles that of both Belgium and China. Her book is called “The Belgian Mandarin”.

Splingaerd, better known in China by many names, including Lin Fuchen (林 輔臣), Su Pe Lin Ge Er de (斯普林格尔德), Bilishi Lin ('Belgian Lin'), or Lin Darin, was born in Brussels in 1842 and grew up as a foster child in the farming town of Ottenburg, southeast of the capital.

Labelled the “Belgian Marco Polo” of his times, his Belgian roots and status as a Chinese mandarin gave him a unique and highly regarded perspective on Chinese-Belgian affairs. It greatly facilitated his effectiveness as a liaison on multiple Sino-Belgian projects in the late 19th century.

Historical background

Splingaerd was born in the post-revolutionary years of Belgium’s secession from the Netherlands. A mere dozen years earlier, the Belgian Revolution had established the Kingdom of Belgium. But, it wasn’t until 1839, three years before Paul’s birth, that the Treaty of London finally recognized Belgium as an independent country.

The year of his birth, 1842, was also the year that China was forced to open its doors to the West. It signalled the end of the first Opium War, which was started in 1839 and instigated by British-Chinese conflict over trade and China’s sovereignty.

Tramway of Tianjin. Following the 1858 Treaties of Tianjin, several Western nations established concessions in Tianjin. The Paul Splingaerd story was the subject of a recent exhibition at the ULB in Brussels, which also focused on relations between Tianjin and Belgium.

It ended with the signing of the Treaty of Nanking; in which Hong Kong became a British territory and the ports in Shanghai, Amoy, Canton, Ningpo and Fuchow were established. Further treaties and concessions with Britain and France swung the door even wider ajar in the ensuing years.

The Second Opium War (also called the Arrow War) from 1856-1860 gave a foothold to even more foreign powers—leaving in its wake a China now completely open to foreign traders from everywhere.

Upbringing in Belgium

On the very day of his birth on April 12, 1842, Paul Splingaerd was left at a Brussels orphanage run by Catholic nuns. He was “tucked into two warm shirts, a hooded jacket and a blanket with a birth certificate indicating the baby’s name and date of birth”, as described in Anne Megawan Splingaerd’s book The Belgian Mandarin.

Just six weeks later, he became the foster child of the Després family, from the farming town of Ottenburg, southeast of Brussels. Ottenburg during his youth was marked by crop failure, epidemics and the collapse of the flax industry. As a result, rural areas like Ottenburg lost significant portions of their income.

Overpopulation and growing poverty proved a detrimental obstacle to a proper education for underprivileged children and seriously curtailed opportunities for the poor masses to better their situation.

At 21, Splingaerd left for Brussels to perform mandatory military service and find work. It was there that he encountered Fr. Theophile Verbist, the chaplain at his military school.

Having recently become director of Saint Enfance (Holy Childhood), an organisation established to help abandoned children, Fr. Verbist shrewdly proceeded to enlist suitable prospects for international missionary work in his new order - the now globally renowned Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (CICM).

Creating a Belgian Mission in China was a top priority.

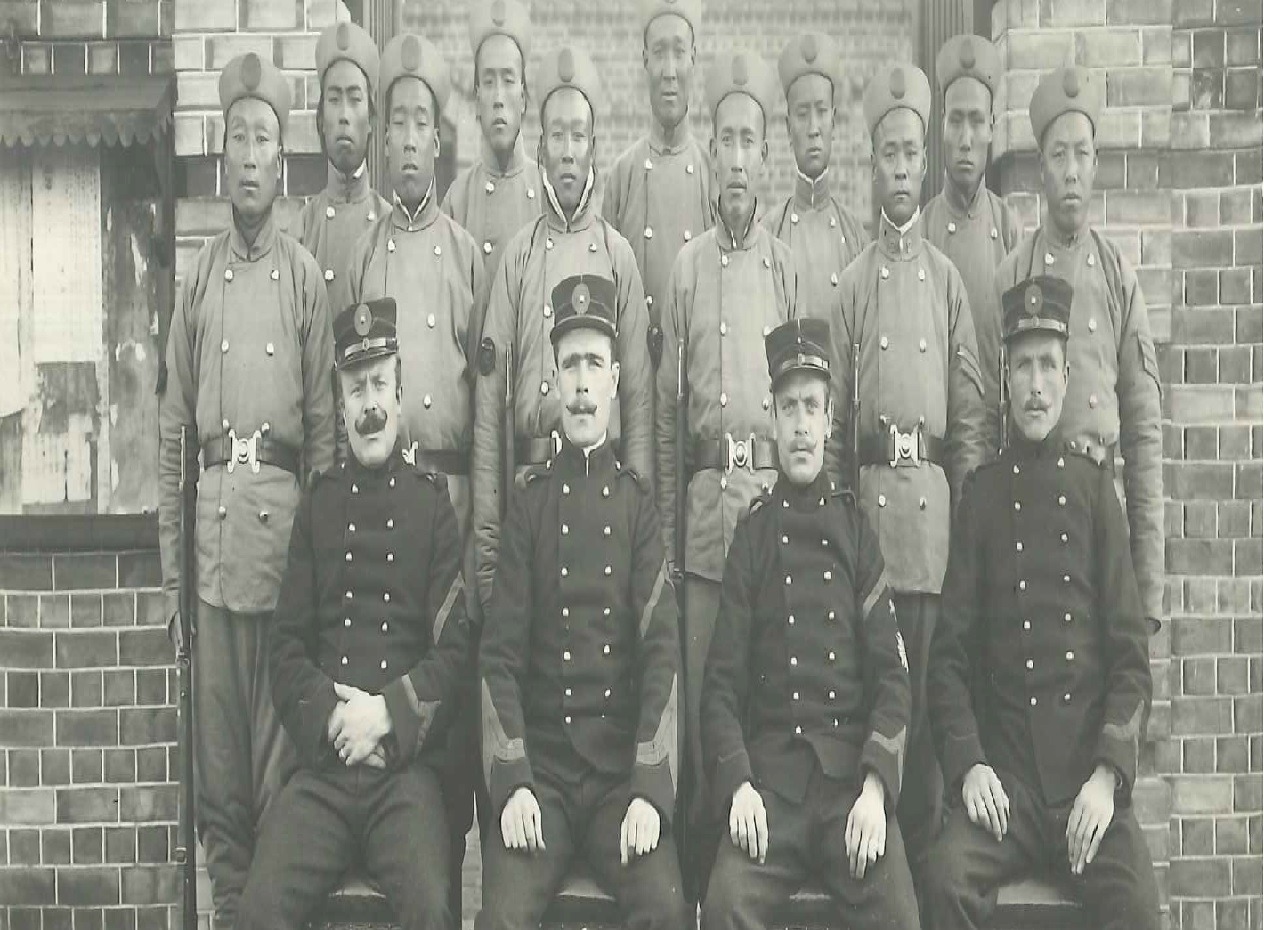

Chinese soldiers with Belgian police in WW1.

Splingaerd’s lack of sophistication and poor education did not dissuade the priest who found him to be “intelligent, quick-witted, patriotic, loyal and a devout Christian”.

In 1863, Splingaerd left his position as an assistant to a local handyman to join Fr. Verbist’s first recruits performing similar duties. His decision to accept this post forever changed the tangent of his life. In 1865, he left Belgium for China with Fr. Verbist and three other founding priests, as their handyman and lay helper.

Career in China

After Fr. Verbist unexpectedly succumbed to typhoid fever in 1868 at the age of 45, Splingaerd, in rethinking his future, left the mission for Beijing after his death. But, he remained in contact with the mission for years through visits and the use of his clout when help was requested.

His friend and German craftsman, Laurent Fransenbach had arranged a job for him with the German/Prussian ministry, where he himself was employed.

Fransenbach had worked with Paul at the Belgian Mission after arriving there with the second wave of priest recruits. His agreement with the mission was terminated after personality conflicts with Fr. Verbist and behaviour that reflected his discontent with the lifestyle.

It was at the embassy that Splingaerd met and became a guide and interpreter for the eminent German geographer and geologist, Ferdinand von Richthofen, famous for having coined the termed “Silk Road”.

While subsequently running a fur and wool trading business in Mongolia (1872–1881), Splingaerd was called by Viceroy Li Hongzhang to serve as Customs Inspector at the far western post of Jiuquan (also known as Suzhou) on the border with Xinjiang.

During his 14 years in Jiuquan, where he was made Third Grade Mandarin with sapphire button – the highest grade for a foreigner – he ran the Suzhou smallpox clinic, and fostered understanding and appreciation of Westerners, their culture and their technology.

After his Jiuquan assignment, Splingaerd was called upon by agents of Leopold II of Belgium to use his understanding of the Chinese language and protocol to negotiate revisions to a contract for the construction of the Beijing-Hankou railway.

His successful efforts were rewarded with a knighthood, and Splingaerd received a medal designating him a Chevalier de l’Ordre de la Couronne (Order of the Crown). He passed away in 1906 in Xi´an, China.

An inspiration for many

Many explorers, including Richthofen's student, the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, and Russian geologist Vladimir Obruchev, have written about their unexpected encounters with the red-bearded Belgian Mandarin.

Splingaerd has also been the inspiration for characters in at least two novels: Vladimir Nabokov’s last novel, The Gift, and the character Mo-sieu in Jean Blaise's “Maator le Mongol”. Belgian playwright Tone Brulin also based his musical, “De staart van de mandarijn”, on Paul's life.

The Belgian mandarin with his family in China

On the 100th anniversary of Paul's death, a statue was erected in his honour by the regional historical society of Ottenburg (Huldenberg). In 2008, in the city of Jiuquan, another statue was erected in his honour.

Anne Megawan’s 13 years of digging for information about her relative rewarded her not just with information on her great grandfather, but also with the discovery of fellow Splingaerd descendants across the globe. Of Paul and Catherine Splingaerd’s 13 known children, only four of them had children.

In 2009, a reunion of Splingaerd’s descendants met in Lanzhou, China, on the centennial of the First Iron Bridge Across the Yellow River. It had been Splingaerd himself who had proposed a bridge for the city of Lanzhou. Today, it is known as Zhongshan Qiao (Sun Yatsen Bridge).

Anne, who lives in Los Angeles, recalls, “We were given the unexpected honour of being conferred honorary citizenship to the city. The televised event in front of dignitaries, drummers, a full orchestra and fireworks made us feel quite special”.

The Splingaerd story was the subject of a recent exhibition at the ULB in Brussels, which also focused on relations between Tianjin and Belgium. Charles Lagrange, the museum curator, said, “His is, without doubt, an absolutely fascinating story”.

The story is told in all its glory by his great granddaughter. There are plans for the book to be translated into Chinese, meaning that both Belgians and Chinese can, fortunately, learn more about the man they called “The Belgian Mandarin”.

By Martin Banks

| 120 years of shared history between China and Belgium 120 years ago, Viceroy Li Hongzhang met his majesty Leopold II at the Royal Palace in Brussels on the occasion of an official dinner, which he had organized in his honour. The dinner has been the foundation of mutual co-operation between Belgium, the fifth industrial power of the time, and China, an empire of 400 million inhabitants, which wanted to enter the circle of modern nations and of which Li Hongzhang was one of the craftsmen. The first contacts between the Belgians and China had already been established more than two centuries earlier when Jesuit Father Ferdinand Verbiest had put his scientific skills at the service of China’s Emperors. As much as the Belgians were all animated by an unshakeable faith in the future of the great Chinese nation, the Chinese trusted this small industrialized country with no colonial claim, and from which they could benefit from the experience. Whether it was the Mandarin Paul Splingaerd who served Li Hongzhang for more than 20 years, or the engineer Jean Jadot who built 1,200 km of railway lines under very difficult conditions, or the Brussels bankers, whose boldness and business acumen would be behind ground-breaking initiatives, or Father Lebbe, whose determination to give back to the Chinese control of their destiny: they all contributed to the Middle Kingdom’s benevolent view of Belgium. The Chinese returned the favour by sending their forces to help the allies during the First World War and by contributing generously to the reconstruction of the country. Later, some future cadres of the New China would come to study in Belgium, thereby confirming their confidence in its know-how. Collaboration between the two countries continues today at the industrial, commercial and cultural level. |