The Cyprus issue is one of the world’s longest running international conflicts. Despite an UN-led peace process a settlement has remained out of reach. The latest round of talks in June 2017 in the Swiss ski resort Crans-Montana collapsed after 10 days with both sides blaming each-other for the failure.

At a recent policy briefing (27 February) arranged by the European Policy Centre in Brussels, political scientist James Ker-Lindsay shed light on the obstacles in achieving a solution to the conflict and the risks if no solution is found soon.

Professor Ker-Lindsay is considered a leading expert on the Cyprus issue and was a member of the British team at the talks at Crans-Montana. He is not optimistic about resolving the issue any time soon: “In Crans-Montana we were closer than ever but missed a historical opportunity.” He identifies three remaining problems.

On the governance of a united island, likely in the form of a federation, the issue of a rotating presidency is sensitive to the Greek-Cypriots who make up 80 % of the population. In his view, one way to get around this problem is to replace the current presidential democracy by a parliamentary democracy with an executive prime-minister and ceremonial president. However, this is unlikely to make it on to the agenda as the two sides seem committed to a presidential system.

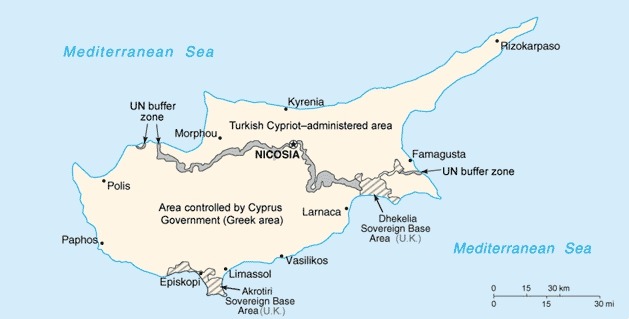

As regards territory and property, the major sticking point was the town Morphou on the northwestern part of Cyprus. Maps were even exchanged where the Turkish-Cypriots agreed to reduce the current territory under their control to about 29% of the island. When the talks broke up in acrimony, however, the maps were recalled.

But what brought down the talks was the security issue, in particular the withdrawal of the estimated 40,000 strong Turkish force from the northern part. The security proposals in the talks were sensitive and Ker-Lindsay preferred not to enter into any details.

Asked by The Brussels Times about the presence of the Turkish troops, he confirmed that Turkey had agreed to withdraw some troops but did not specify which number or over which period. The issue concerning the Turks who have settled in the northern part is also sensitive. “There is no exact figure on their number. For humanitarian reasons they should be allowed to stay.”

Another related issue is the fate of the British sovereign military bases in Cyprus. A British withdrawal might influence Turkey to withdraw its troops. Ker-Lindsay noted that the UK had repeated its 2004 offer to give up half of the territory belonging to the bases. But this would probably not satisfy the Greek-Cypriots. Whether UK still has a strategic reason to keep them was not clear.

In hindsight, was it a mistake to admit Cyprus to the EU while leaving the issue unsolved? Since then, EU seems to have learned the lesson. The recent strategy for the candidate countries in the Western Balkans makes it clear that any bilateral conflicts must be solved before accession.

“We must look at the context back then,” he replied. “EU couldn’t allow any third party to have a say on membership. The mistake was that there were no safeguards in the period leading up to membership. Now we understand the mistake and don’t want to repeat it in the Western Balkans.”

UN-led negotiations on solving the Cyprus issues have now been going on for years but failed. What does this tell us? Should EU, whose role has been limited to that of an “active observer”, step in and act as a mediator, using its leverage not only on the two sides in Cyprus but also on the “guarantor powers” Greece and Turkey?

“I don’t think that having EU as a mediator would be a good idea,” Ker-Lindsay replied. “EU cannot play that role since it wouldn’t be neutral or seen as neutral. Cyprus and Greece are both member states and Turkey, formally still a candidate country, would oppose EU as a mediator.”

But the current situation isn’t sustainable, according to professor Ker-Lindsay. Both sides seem to ignore the changes taking place in the region and have been reluctant to take the last few steps to reach a compromise solution. The discovery and exploitation of natural gas in the territorial waters of Cyprus should serve as an economic incentive for such a compromise.

“We are running out of time,” concluded Ker-Lindsay. “My greatest concern in the absence of a solution is that northern Cyprus could eventually be annexed as a province by Turkey.”

Neither the Turkish-Cypriots nor the Greek-Cypriots would benefit from such a scenario. They need to enter frank discussions and reestablish trust.

| Brief background The Cyprus issue refers to the division of Cyprus into a Greek-Cypriote part, the Republic of Cyprus, and a northern Turkish-Cypriote part on one-third of the island, the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which is only recognized by Turkey. Tension between the two communities prevailed after Cyprus become independent in 1960. However, the current situation is a direct result of the Turkish invasion of the northern part in 1974 in response to a military coup in Cyprus for union with Greece. An UN peacekeeping force is deployed on the island to prevent hostilities and separate the two sides. Cyprus became an EU member state in 2004 on the assumption that the conflict would be resolved under the so-called Annan plan, named after UNs former secretary-general Kofi Annan, but his plan was rejected by the Greek-Cypriots in a referendum while he Turkish-Cypriots accepted it. Since then several attempts have been made to reach a compromise that would be acceptable to both parties. The northern part finds itself in a legal limbo without access to EU’s internal market while receiving EU funding for institution building and infrastructure to prepare itself for becoming part of EU once the conflict is solved. |

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times