Do you feel poorer? You may not realise that people in Brussels have had a big pay cut over the past year. But step on to Eurostar at the Gare du Midi and once you arrive in London, you’ll feel the pinch. The British capital has never been cheap, but it is now much pricier for people who are paid in euros. In March 2014, 100 euros bought 83 pounds. Now they get you only £72 – 13 per cent less. Those considering a shopping trip to New York or a holiday in Florida will feel even more impoverished. A year ago, 100 euros stretched to 139 dollars. Now you’d get only $106 – 24 percent less! By the time you read this, the euro may even be at parity to the dollar.

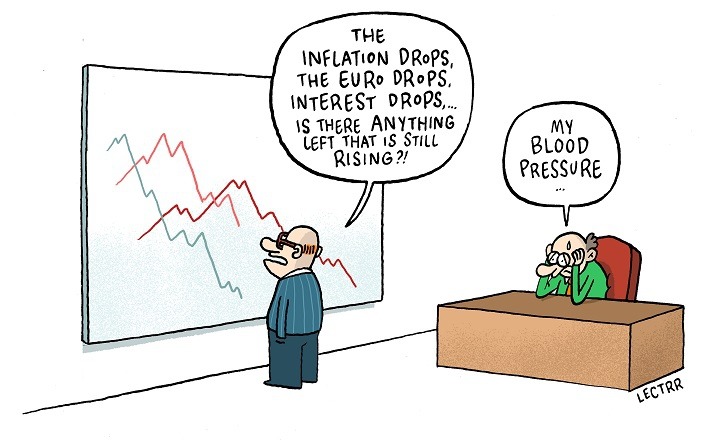

Currencies move up and down a lot, but that is still a big move, especially since the euro’s fall accelerated in the early months of this year. Why has it happened? And how else will it affect the economy?

Currency shifts are unpredictable: a mind-boggling $5.3 trillion changes hands each day on foreign-exchange markets, for all sorts of reasons. But a plausible explanation for the euro’s plunge is as follows.

Because the eurozone economy is depressed by huge debts, inflation is expected to be very low in coming years. It may even remain negative. So investors think interest rates are going to stay near zero for the foreseeable future. The European Central Bank is also doing its best to drive governments’ borrowing costs even lower. On 9 March, the ECB began buying lots of government bonds with freshly created money through its programme of quantitative easing (QE), a move which markets had long anticipated.

Many eurozone governments – including Belgium’s – can now borrow at negative interest rates. That sounds crazy: why would anyone lend to a government that promised to pay back less than it borrowed? For one thing, big institutional investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies, are obliged to hold government bonds for regulatory reasons. As, indeed, are banks. And while investors are guaranteed to lose money if they buy negative-yielding bonds and hold them until they are redeemed, they may still be able to make a profit if they sell them on before then. So long as bond yields continue to fall and therefore their prices to rise, investors can still make positive returns with negative interest rates.

The situation in the United States and Britain is very different. Unlike the eurozone’s economy, theirs are growing strongly. Unemployment has fallen to around 5½ percent, half the rate in the eurozone. That led the US Federal Reserve to halt its own QE programme late last year. Investors are now expecting central banks to start raising official interest rates at some point over the next year. As a result, US and UK government bonds pay higher interest rates than eurozone ones. That makes it look profitable to sell eurozone bonds and buy American ones, or to borrow cheaply in euros and buy dollars to invest in American assets. And if some investors anticipate that this is what others are going to do, they can speculate that the euro will fall and the dollar rise, accelerating the euro’s decline. Until, of course, something unexpected happens, or investors’ mood changes…

What does a weaker euro mean in practical terms? As well as making trips to London and Los Angeles more expensive, it pushes up the prices of imports more generally. Like oil, for instance. Motorists cheered last year as the price of oil halved within the space of a few months. While the high taxes on petrol in Belgium muted the impact on prices at the pump, the savings still gave households more money to spend on other things and cut businesses’ costs. But the euro’s collapse this year has unwound some of those gains. While the oil price has continued to fall this year in dollars, it was up by 10 percent in euros by mid-March.

On the plus side, the weaker euro makes Brussels cheaper for foreigners. The cafés and restaurants around the Grand-Place are suddenly more affordable for visiting Britons, Swiss and Americans. Chinese tourists may splurge more on Belgian chocolates and other luxuries. Property looks like a snip too. And that may just tilt the balance towards locating in Brussels for an international company that is weighing whether to base its European operations in Belgium or Britain.

But most exports aren’t like tourism, which is produced locally, consumed by foreigners on the spot and priced in euros. Belgium’s biggest export by far is chemical products. Belgium’s production tends to rely on imported inputs, notably oil. So a weaker euro is a mixed blessing: it could allow a Belgian company to charge less than its competitors in the British market, and thus boost sales, but it also pushes up costs.

Since the euro’s weakness may only be temporary, companies may be tempted to pocket any gains as fatter margins. That’s what British companies mostly did after the pound collapsed by 25 percent in 2007–9 – and as a result, UK exports didn’t rise. The incentive not to cut prices is even greater for producers of branded goods. If Pierre Marcolini cut the price of its chocolates, would Harrods shoppers buy more of them? Or might they think the quality had fallen and buy fewer?

Remember too that while Belgium is a small and very open economy – exports and imports add up to 164 percent of economic output – more than half of that trade is with other members of the monetary union. For all those reasons, a weaker euro may not lift Belgian exports as much as the authorities hope.

The eurozone as a whole is a very large economy, second only to the United States. Its exports – worth just under €2 trillion in 2014 – are even greater than China’s. So it’s asking a lot of the rest of the world to buy enough additional eurozone products to offset depressed domestic spending and lift the entire, €10 trillion eurozone economy, especially when global demand isn’t that strong.

It’s ironic that eurozone authorities are counting on a cheaper currency to boost growth. After all, the euro was created out of a belief that currency shocks were a problem that Europe could do without. But a currency jolt is unlikely to be enough to shake the eurozone out of its slump.

The fall of the Euro – disaster or opportunity?

This is an opinion article by an external contributor. The views belong to the writer.