On the 24th of October 1945 the United Nations Charter entered into force. On that day, following ratification by the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and a majority of other signatory States, the United Nations finally came into existence.

75 years later, humanity finds itself in very hard times, facing unprecedented challenges and the devastating consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic. In this not ideal situation to celebrate one’s birthday, the United Nations Day was marked by sobriety and resilience. Nevertheless, after concerts and official remarks, very positive news galvanized the supporters of nuclear disarmament.

The news came from Tegucigalpa, where the Minister of foreign affairs of Honduras, Mr Lisandro Rosales, signed the country’s ratification to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Also known as the ‘Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty’, the TPNW has now reached its required number of ratifications, and it will enter into force om 22 January 2021.

Reactions

On one side, solemn declarations have enthusiastically welcomed the 50th ratification as a historic milestone. At ICAN (Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2017), the Executive Director Beatrice Fihn affirmed that “This is a new chapter for nuclear disarmament.”

Truly touching words have been pronounced by Setsuko Thurlow, a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, who said he has “nothing but gratitude for all who have worked for the success of our treaty.” Equally positive has been the statement of Peter Maurer, President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), who referred to “a victory for humanity, and a promise of a safer future.”

Silence reigns in Brussels, as the EU Member States cannot agree on a common position. While a majority of States, by virtue of their NATO membership, maintains that the TPNW “disregards the realities of the increasingly challenging international security environment,” Austria, Ireland and Malta have signed and ratified the Treaty.

The fact that four EU members (Belgium, Italy, Germany and the Netherlands) host US tactical nuclear weapons on their territory might be an additional explanation as to why the adhesion to the TPNW is more controversial on the old continent than elsewhere. The European Parliament, for its part, has recently issued a resolution (21th of October 2020) calling upon the EU’s chief diplomat Josef Borrel to ensure without delay the formalizing of a common position ahead of the NPT Review Conference.

Farce or great success?

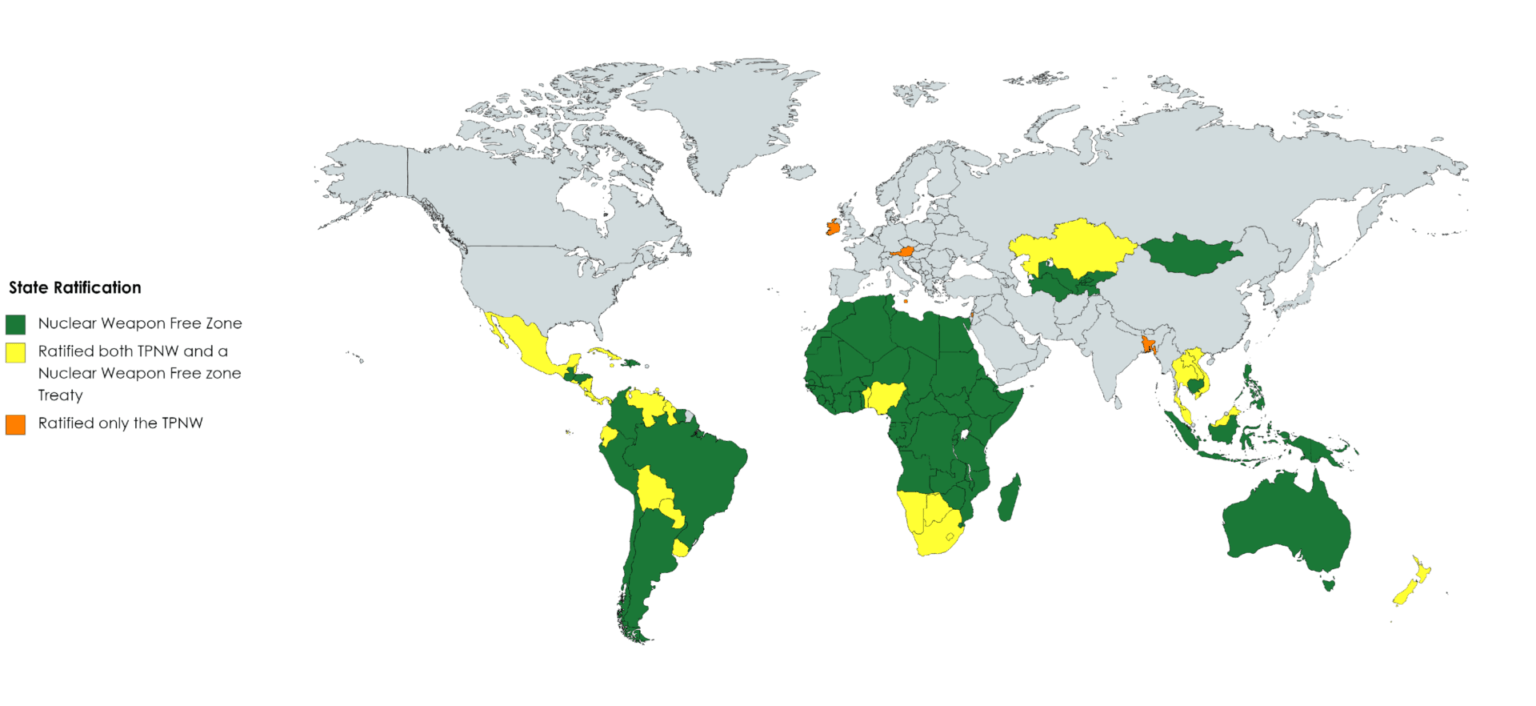

Now that 50 states have signed and ratified the TPNW, it is time to have a closer look at who they are and what legal obligations will be incumbent on them from January 2021. Looking at the map below, one will notice that very few European countries have ratified the TPNW. In fact, the only ones that have are Ireland, San Marino, the Holy See, Malta and Austria. Even though many European countries support the efforts made by nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament organizations, there is one hurdle which none of them has been able to overcome and its name is NATO.

Source: UNODA, data as of October 25th 2020.

Even if NATO's importance in Europe's security is not at the core of our analysis, it is undeniable that a conservative approach towards NATO membership is what ultimately prevents many European States from adhering to the TPNW. This means that with three NATO allies having successfully developed nuclear weapons and 4 others hosting them on their territories, it has become very difficult for European states to openly and actively oppose nuclear weapons. The lack of European support for the treaty is probably not the most relevant note we, the authors, wish to share. This next one however is

Of the 50 states that have ratified the treaty, 42 of them already belong to one of the five Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (NWFZ), meaning that not so much has changed for them in terms of their international legal obligations. Indeed, both the TPNW and NWFZ treaties establish a prohibition on developing, testing, producing, acquiring, stockpiling and stationing nuclear weapons. On the contrary, the decision to ratify the TPNW has been a bigger step for Austria, Bangladesh, the Holy See, Ireland, the Maldives, Malta, San Marino and Palestine, that do not belong to any NWFZ. It is not irrelevant that five of them are located in Europe, and three are EU members.

The above-reported data lead us to the following question. With no nuclear weapon state, no NATO ally, and only eight non-NWFZ states ratifying the treaty, will the ‘Ban Treaty’ be able to change anything in the status quo of international security? In the short term, the answer is no. After the Treaty enters into force, there will be just as many nuclear weapons in the world as there are right now.

Building international pressure

However, the real value of this treaty is in its influence over time. It is expected that many more states will sign and ratify it, which will ultimately strengthen the social norm that nuclear disarmament is desirable for everyone and should be actively pursued. Looking at other subfields of disarmament, we observe that this modus operandi is not something new.

When a treaty to ban anti-personnel landmines was first being discussed, many governments were reluctant, to say the least. Then, when the idea of a ban started to garner broader support, the social pressure on the most recalcitrant states grew, making the treaty more successful over time.

This brings us to the next challenge for the entire disarmament community, namely, to keep the momentum going. The entry into force of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is a historic moment which will gain a lot of international attention. Yet, the mission remains unchanged.

If we want to live in a world free of nuclear weapons, many more states will have to ratify the treaty. The ratifications of 35 signatory states are still missing, thus exempting them from legally-binding obligations. Persuading them to take the step could be a good way forward.

Maxim Schoofs and Francesco Pezzarossi