Political maps of the world are interesting artefacts. As the writer Amitav Ghosh reminds us in his new book, these maps are full of places that were christened by settlers who wanted to create new versions of the places they had left behind. And so we have New Hampshire, New York, New England, New Zealand, New Ireland, New Orleans, etc.

The so-called “new world” was in fact an Old World populated by tribes or peoples that had been around for millennia, and the lives of these tribes were centered around rites and agricultural practices that were much older than the Dead Sea Scrolls. So what arrived in the Americas, in fact, was a new world of technology and state-organized violence.

British Columbia, seen in this light, is a “British” place that pays homage to a Genoese captain who enslaved the people of Hispaniola. El Salvador is named after the Savior of the Bible. The Philippines or Filipinas, a vast archipelago of incomprehensible natural beauty to the treasure hunters who discovered it, takes its name from King Felipe of Spain, a monarch who spent his days seated at his desk signing oficios. I don't know who lived in Nova Scotia or Newfoundland when the armed Westerners arrived. But I suspect they didn't think there was anything “new” about these places.

Our political maps of the world also remind us of our talent for enlightened despotism. Despotism and war go a long way in explaining the political map of Europe for instance. France used to be a multilingual mosaic of peoples at odds with the king’s tax farmers and soldiers. Iberian history tells a similar story: Castilian was once a ruffian’s dialect to Valencian ears.

Tribalism and communalism (besides war and tax farming) do not fully explain why we have these political maps however. What also explains them, in my view, is our vision of the world as an inert place that is here to provide us with resources. Note the absurdity of this last sentence: the world is here —a rock in space that we happened to find— to give us what we want.

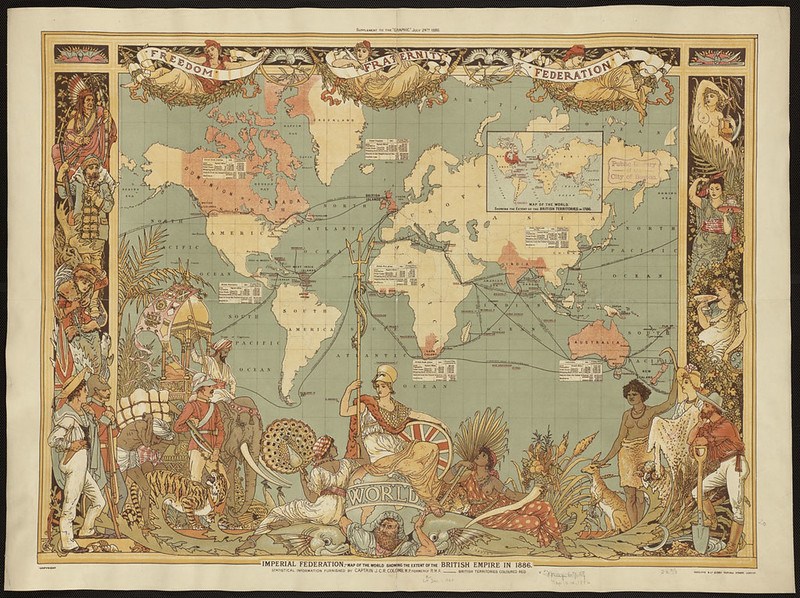

Tribes, kingdoms and later empires fought over territories and resources. And so we ended up with places like “Léopoldville” (Kinshasa) and “Rhodesia” (Zimbabwe and part of Zambia) and all those “new” places or “Neo Europes” where Europeans sought to mine the inert planet.

One 17th-century settler described the wilderness of North America as a “mart”, a commodity market ready for plunder. We drew maps of commercial conquest that, in many cases, became maps of exclusion: They designate supposedly greener pastures enclosed by laws and prejudices.

These maps reflect administrative and political realities. But if we ask our imperial mapmakers and their modern-day political incarnations what is special about these maps, or what is special about a place like Rhodesia, they would probably say something like this: Well, there’s gold in Rhodesia. It’s part of our value chain! But is this the best we can do for the place? Is there nothing else in Rhodesia but gold or diamonds? How about Léopoldville? Warehouses full of ivory and nothing else?

If you sat down to read, say, a general history of Ecuador, wouldn't you would want to read something more than a who’s who of generals, thieves and priests? An Ecuador without rivers, forests, geological deposits, weather patterns, animals, sea currents, tribes, stalls filled with produce, incantations or charms would be a charmless place. A country that would bear little resemblance to the country that anyone with a rudimentary ecological education would encounter in their travels.

The modern-day Leopolds and commodity hunters

More the point: It would be the same Ecuador you would encounter in our political maps of the world and their underlying Leopoldine vision of the world (after King Leopold of Belgium). It’s no wonder kids spin these globes until the mechanism comes loose, as if they were trying to rid them of all those princely fictions and imperial labels that we attach to them. This is how these globes discard geopolitical absurdities such as New Spain or French Sudan.

Kids, it seems, are more attuned to Geological Time. If Geological Time could speak our language, it would chew up our notions of the world-as-a-silver-mine or the world-as-resource (Amitav Ghosh) or the world-as-a-collection-of-political-parcels and spit them out. But we don't live our lives on such timescales. So the here and now matters: what we must protect we protect for ourselves and those who will follow.

Picture King Leopold II in his studio. He is gazing at a large map of Africa on the wall, where he sees nothing but gold, diamonds, copper and ivory. He sees “spheres of interest” where there is a biosphere. Like the rest of us, he’s susceptible to greed and shortsightedness. He wants to amass enough wealth to build his greenhouses and his summer house near the coast. And the map on the wall tells him how may get it: I need to occupy Khartoum, he tells himself after he’s done terrorizing the people of the Congo Free State. So where does it end?

It’s worth noting that more than a hundred years after King Leopold and Queen Victoria we are still trying — and failing — to regulate our supply chains. We still can’t agree on what rules we need to keep our modern-day Leopolds and commodity hunters from occupying Khartoum. Leopoldine and Victorian attacks on the living world continue to this day. In the past we had Chartered Companies that argued their case before the relevant authorities (the natives, Your Highness, need Commerce, Christianity and Civilization). Now we have industry groups, lobbying firms and contemptible “creatives” who wield arguments that are far more sophisticated than the 3 C’s.

True, not every CEO has a Leopoldine vision of the world. But it only takes one Wall Street Leopold or a democratically elected Leopold to cause lasting environmental damage and terrible human rights abuses. Leopold still reigns in the world of fiduciary duties to the shareholders and no one else. Leopold is the millionaire guy who, faced with the shadow of a regulation, shouts jobs! when he means capital gains. Given the sad reality that many people in power see the world like this — the world as a silver mine or soy monoculture where amassed wealth pays no taxes and where pollution is free — what we need, then, are rules. But who will write and enforce them?

Someone has to, and perhaps it’s fitting that Europe — the new Europe of smallpox and caravels — should attempt to lead the way. Because the mine cannot give as much as we’re prepared to take. The mine has boundaries. It is, in fact, a finite planet.