If you have lived before in Berlin or in Vienna, in Paris or in London, or even in Antwerp, you may often have wondered, sometimes with some exasperation, why Brussels is not a bit more like them. Why does the city of Brussels - more precisely the Region of Brussels Capital - still consist of nineteen autonomous municipalities, with their own administration, schools, taxes, cleaning services, welfare offices and parking rules? In other cities, the absorption of neighbouring villages by the growing agglomeration led long ago to the creation of a large municipality which includes today if not all, at least a big chunk of the metropolitan area.

Comparing Brussels with Vienna and Berlin is particularly relevant, because of a number of important similarities. Each of the three cities is the capital of a member state of the European Union. Each of them forms one of the constitutive components of a federal state: Brussels is one of the three regions of the Kingdom of Belgium, Vienna is one of the nine Länder of the Republic of Austria and Berlin one of the sixteen Länder of the Federal Republic of Germany. Each of them forms a tiny component in terms of size - Brussels and Vienna cover only 0.5% of their respective countries’ areas, and Berlin 0.25% -, but a far more significant component in terms of population - 10.5% of Belgium’s population live in Brussels, 20% of Austria’s population in Vienna, 4% of Germany’s population in Berlin. Moreover, each of them is entirely surrounded by another component of their respective federations: Brussels is an enclave in Flanders, Vienna an enclave in Lower Austria, and Berlin in Brandenburg.

So, what happened in Vienna and Berlin that has not happened so far in Brussels?

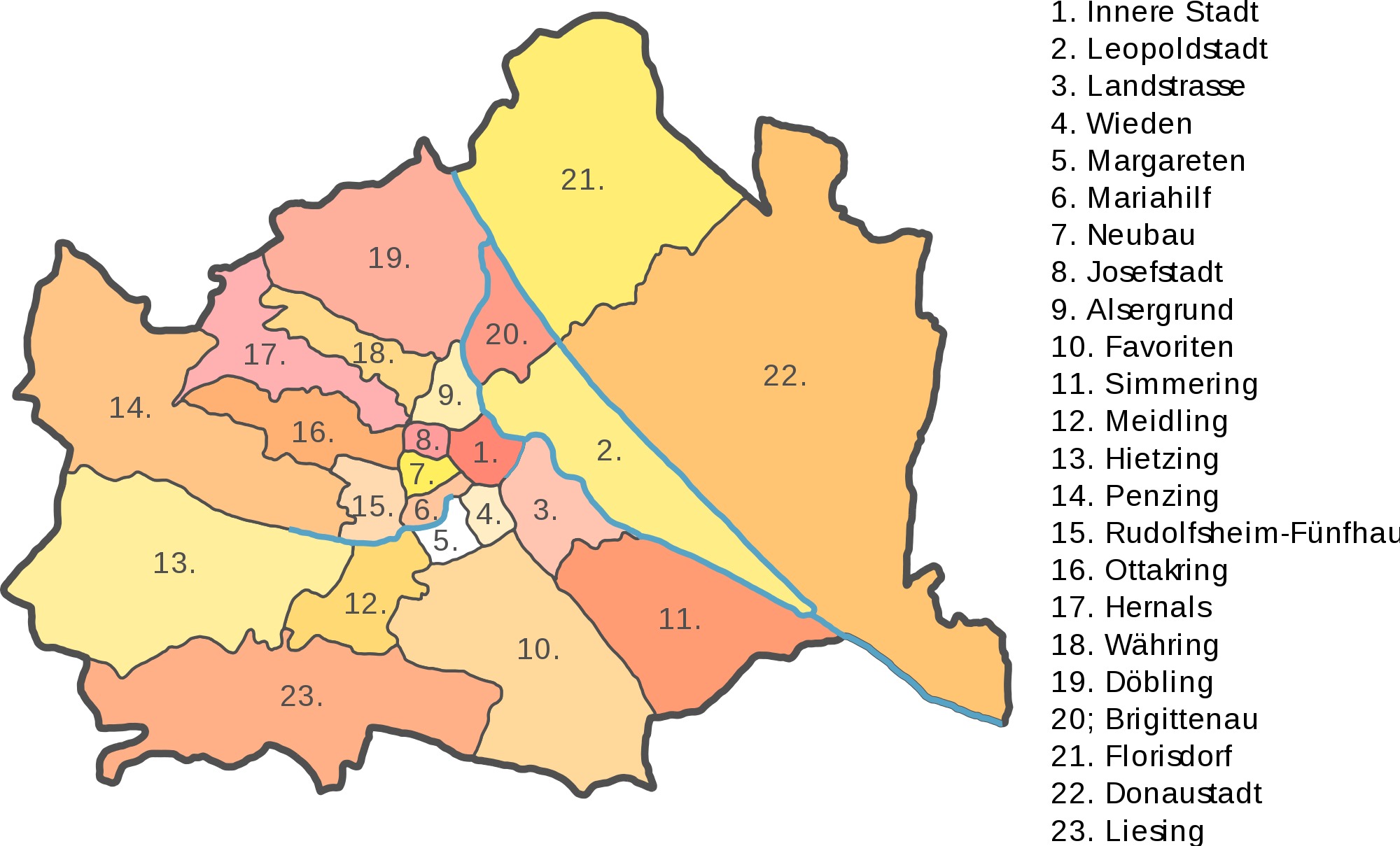

Vienna starts its expansion through the absorption of neighbouring rural municipalities in 1850. By 1905, about twenty of them have been transformed into districts or Gemeindebezirke of a single municipality. After the Anschluss, in 1938, a massive expansion to nearly three times Vienna’s current area is decided by the German authorities, but this decision is reversed after the war. In 1954, only two more Gemeindebezirke are definitively added to the municipality, which brings their number up to twenty three, with populations varying from less than 20.000 inhabitants (Innere Stadt) to nearly 200.000 (Favoriten). The municipality of Vienna has a single Bürgermeister, exercises the bulk of the local powers and raises all local taxation. It now hosts a population that is about 50% larger than that of the Brussels Region on a territory that is three times as large.

Vienna

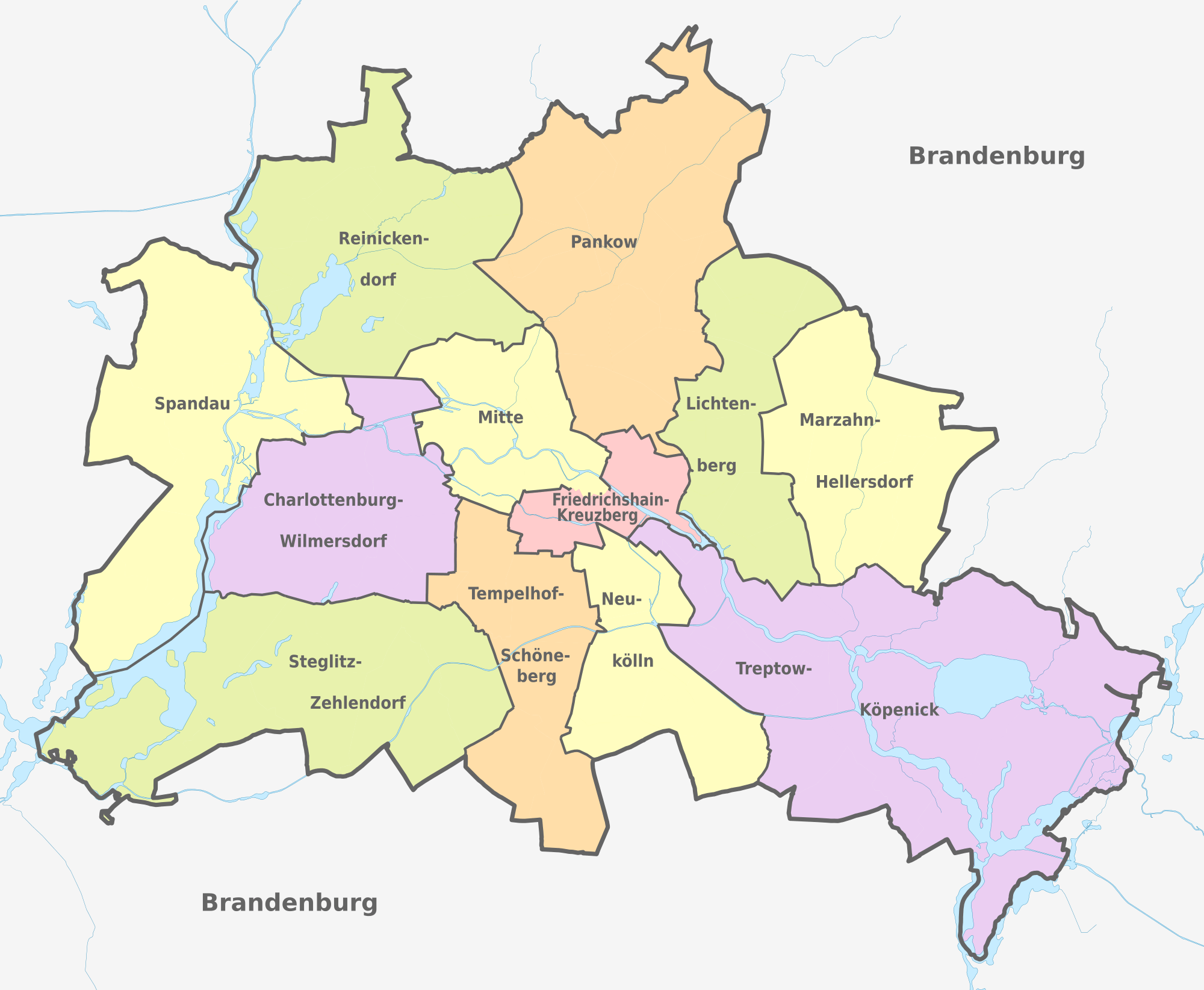

In Berlin, the big leap happens in 1920, when a large number of municipalities are added to the historical centre in order to form a single municipality consisting of twenty three Bezirke of very unequal sizes and populations. In 2001, a decade after reunification, a major restructuring reduces the number of Bezirke to twelve with comparable populations ranging from nearly 230.000 (Spandau) to 370.000 inhabitants (Pankow). The city of Berlin as a single regierender Bürgermeister, exercises the bulk of the local powers and raises all local taxation. It now hosts a population that is about three times that of the Brussels Region on a territory that is over five times larger.

Berlin

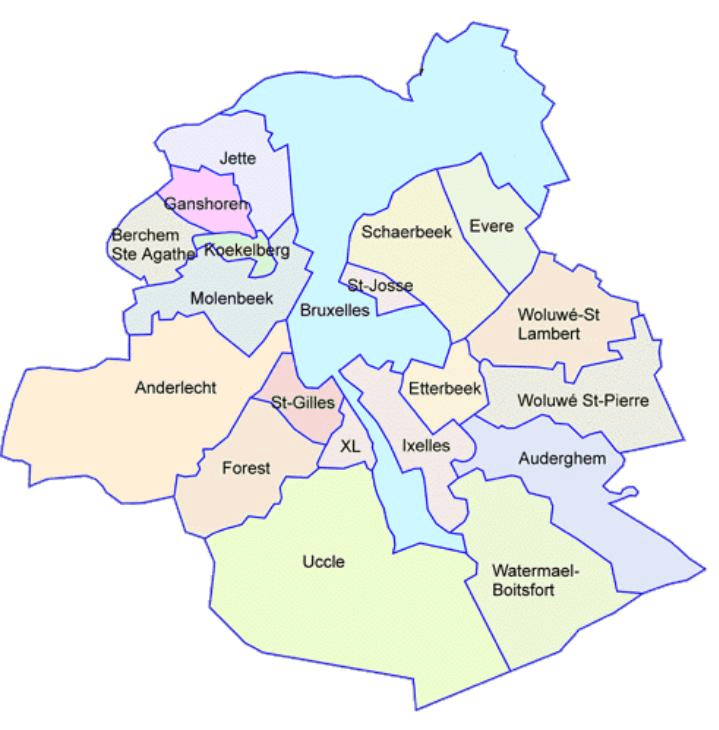

The Region of Brussels, by contrast, consists of nineteen autonomous municipalities, with populations ranging from about 20.000 (Koekelberg) to over 170.000 (Bruxelles-Ville). Each of these has its own bourgmestre and enjoys extensive autonomous powers, inclusive in matters of taxation. Has Brussels never made an attempt to tread the same path as its big sisters Vienna and Berlin? It certainly has.

In 1853, a couple of decades after the creation of Belgium as an independent state, the municipality of Brussels is expanded to the east of the Pentagon at the expense of the communes of St Josse, Schaarbeek and Etterbeek. At the instigation of the Société civile pour l’agrandissement et l’embellissement de la Capitale de la Belgique, a real estate company headed by Ferdinand de Meeüs, it absorbs what has now become Brussel’s European neighbourhood - the Quartier Léopold and its Extension Nord-Est (today’s Quartier des Squares), all the way to what was to become the Parc du Cinquantenaire - in order to facilitate the development of a residential area for the upper class of the young independent state.

Another step is accomplished in 1864 in order to overcome the fierce opposition mounted by the commune of Ixelles to the building of the Avenue Louise. A strip of land joining the Palais the Justice to the Bois de la Cambre, including what is due to become the main site of the Université libre de Bruxelles, is appropriated by the municipality of Brussels, thereby cutting the commune of Ixelles into two pieces.

Finally and most significantly, in 1921, the municipality of Brussels expands to the North by absorbing the whole of the communes of Laeken, Haren and Neder-Over-Heembeek, over 40.000 inhabitants at the time. This makes the royal palace (in Laeken) and Belgium’s first airport (in Haren, on the site of NATO’s new building) part of the territory of Brussels. But the main purpose is to transfer to the municipality control over both banks of the canal so as to facilitate the development of Brussels’ harbour.

Had this process gone further, the municipality of Brussels could have seized the bulk of the urbanized area, as Vienna and Berlin had done. But this is where it stopped. In contrast to its Austrian and German counterparts, the commune of Bruxelles-Ville occupies only 20% of the area of today’s Brussels Region and hosts only 15% of its population. Could it have gone further? It certainly looked as if it could back in the 1970s. On the 1st of January 1977, the number of Belgium’s communes is dramatically reduced from 2359 to 596, but Belgium’s two biggest cities, Brussels and Antwerp are not affected. Antwerp, however, follows suit in 1983 by absorbing seven neighbouring communes and thereby becoming Belgium’s most populated municipality, which it still is today. In 1999, these former communes are turned into districts with a directly elected council and some limited local powers, on a model not very different from Vienna and Berlin.

What about Brussels? Why has nothing of the sort happened so far? Why is it unlikely to happen soon? Basically because of one peculiar feature of Belgium’s transformation from a unitary into a federal state in the 1980s. In 1989, nearly twenty years after Flanders and Wallonia, Brussels is given the status of a Region, with its own directly elected parliament and its own government. Just as Belgium’s French-speaking minority is given a guaranteed representation, and thereby a veto power, in the federal government (equal number of ministers with the possible exception of the Prime Minister), Brussels’ Dutch-speaking minority is given a guaranteed representation, and thereby a veto power, in the government of the Brussels Region (equal number of ministers excluding the Minister-President and the junior ministers or secrétaires d’état). Crucial is that there is no similar protection of the Dutch-speaking minorities in the executives (Collèges des bourgmestre et échevins) of the nineteen communes that make up the Brussels Region.

Brussels

This difference explains it all. Any transfer of powers from the communes to the Region, a fortiori a merger of the nineteen communes into a single one that would coincide with the Region - just as the municipalities of Vienna and Berlin coincide with the respective Länder - would entail a shift of power from Brussels’ French-speaking majority to its Dutch-speaking minority, and the Francophones in power, especially if they are active at the communal level, understandably do not want that. Besides this contingent institutional fact, is there any more fundamental reason why powers should be more decentralized in Brussels than in Vienna or Berlin, in Paris or in Antwerp? None whatever. In Brussels as in other cities, interdependencies in a densely populated area raise the same problems and require the same institutional solutions.

Is there any hope for this to change? To get rid of the key obstacle, greater symmetry must be achieved between the “ethnic” allocation of power at the communal and the regional level. Over time, the proportion of Dutch speakers among Brussels residents keeps falling. Thus, according to the latest reliable data (VUB Taalbarometer 2011), the proportion of Brusselers who have Dutch and only Dutch as their native language is now down to 5%. It is therefore argued that their guaranteed overrepresentation in the Brussels Region’s Parliament (19%) and government (de facto 38%) is exaggerated.

This argument is prima facie very persuasive. According to the the same data, however, the proportion of those who have French and only French as their native language is down to 34% (including the many French citizens, who form the second nationality in the Brussels Region). The composition of the Brussels population has been changing rapidly, more rapidly than ever since the beginning of this century. Languages other than French and Dutch are more present than ever, and a growing big third of the residents are being deprived of voting rights at the regional level because of not being Belgians. What this trend challenges is less the guaranteed representation of the “Flemings” than the key organizing principle of political life in the Brussels region: the idea that the Brussels population consists of two mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive ethnic categories, the Francophones on one side and the Nederlandstaligen on the other, with two separate electoral colleges and two separate sets of parties.

Thus, far more radical institutional reform is needed than just weakening the guaranteed presence of Dutch speakers in the regional government - which, incidentally, has the significant advantage of securing a permanent link between the Brussels authorities and the surrounding Flemish region. Even more important than - though not independent of - any institutional change is the building of trust between the two linguistic groups within Brussels. Such trust, essential for the loosening of institutional guarantees, is itself dependent on the relative strength of people’s respective collective identities: do Brusselers primarily feel Brusselers, rather than primarily Flemings or Walloons, French - or Dutch-speakers? And on this score, judging by the latest reliable data, the news is good. This is in the end why there is hope that one day Brussels will manage to become, in the relevant respect, a bit more like Vienna and Berlin.