December of 2017 in Belgium was one of the darkest and most sunless since records began to be kept. According to Belgium's Royal Institute of Meteorology, there were just 16 hours and 17 minutes of sunshine. And not a minute of sunshine between December 18 and Christmas Day. So, southern Europeans may be forgiven for wondering why there are so many solar panels on houses here. But the answer is simple. Some €5-6,000 will today buy you some 16-20 solar panels, including installation, enough to cover an average Belgian family's annual electricity consumption. And even newer network charges on home solar panels are not enough to stop interest in solar panels with payback times of some seven or eight years. Still, unlike southern Europe, going off-grid is not yet possible with just solar panels and battery storage due to the long, dark winter months.

Solar panels are one of the most visible signs of Belgium's struggle to earn its place in the sun when it comes to the transition to a clean and sustainable energy system. In a visionary moment, and a decade before Germany, Belgium decided to phase-out nuclear power. The goal was to make the transition to clean energy, eliminating coal, nuclear or even gas at some point. But unlike Germany, no clear date has ever stuck for long in Belgium. And today, as the deadline for final closure in 2025 looms ever closer, Belgium's governing coalition is under pressure to further delay phasing-out the country's nuclear power plants at Doel and Tihange.

"Complete nuclear phase-out will lead to greater dirty energy imports from neighboring countries such as coal from Germany and the Netherlands. Not by chance those two countries are lobbying hard for nuclear phase-out", says Bert Wollants, a member of the Flemish centre-right N-VA party. Wollants argues that getting rid of Belgium's nuclear plants will make it difficult for the country to meet its goals in reducing carbon dioxide emissions. The N-VA, as a key member of the coalition government, is pushing for a delay in the phase out.

Energy pact

The hesitancy behind Belgium's nuclear phase-out is casting a dark shadow over the country's transition to 100% renewables by 2050. That 100% renewable goal was set out in the so-called “energy pact” signed in December last year by Belgium's four energy ministers, at federal, Brussels, Walloon and Flemish level. The pact does not do away with Belgium's declared nuclear phase-out in 2025. And it still foresees an intermediate step where gas and renewables eventually replace over 50% of electricity that is currently provided by Belgium's seven nuclear reactors.

Belgium currently operates 7 pressurized water reactor at two nuclear plants (Doel and Tihange). As part of the transition goal towards clean energy, a deadline for the closure of the reactors has been set for 2025, with a 100% renewables target by 2050.

But Kristof Calvo, who leads the Green party in Belgium's chamber of representatives, suspects that the current coalition government is secretly planning to postpone the nuclear phase out. Disappointing the public would only come later with a final decision in 2021, in between federal elections. "There is an overwhelming majority to confirm nuclear phase out now", says Calvo. "We hope that the coalition parties will not be taken hostage again by N-VA", he adds.

Sam Van den Plas, Senior Policy Officer, Climate and Energy in WWF's (World Wildlife Fund) European policy office, believes delaying the phase out constrains the shift to renewables.

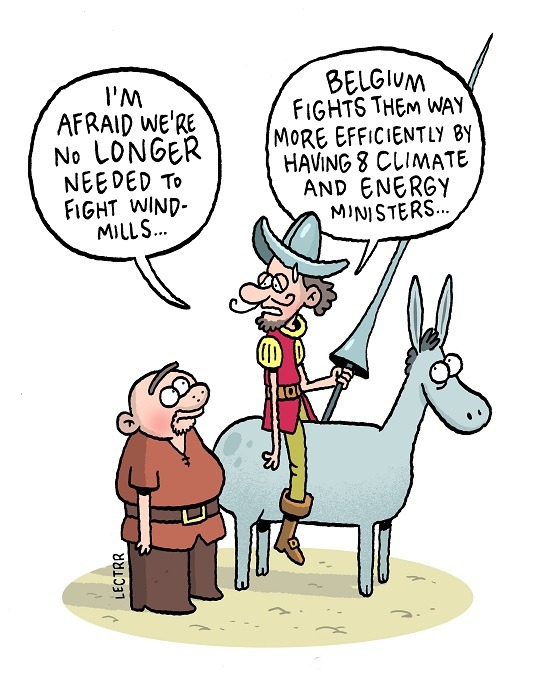

"Belgium needs to uphold its nuclear energy phase out. The ongoing questioning of this deadline is undermining a stable investment framework for renewables investment", says Van den Plas. He argues that Belgium not only risks falling behind on meeting its 13% renewable energy target by 2020 but is also underperforming on energy savings and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. "The Belgian institutional set-up is not making things easier, with a total of eight ministers in charge of climate and energy policymaking", he says.

The French-speaking renewables association APERe argues nuclear power is distorting the energy market because its real cost ― include safe dismantling and storage of nuclear waste — will only be paid by future generations. APERe doubts the phase-out in 2025 is high on a list of renewable investment disincentives right alongside politicians retroactively changing rules and support measures.

To back the case of renewables, APERe secretary general Benjamin Wilkin underlines their ever lower cost compared to traditional fossil fuel and nuclear energy. "The year 2017 is marked by the dramatic fall in solar and wind costs. Their competitiveness now exceeds traditional energy in many places", said Wilkin.

Divided Belgium

Every country witnesses the same battle between progressive renewables and more conservative industrial lobbies. Belgium's path to clean energy has been further hindered by quarrelling among its three regions. With offshore wind farms, biomass and large projects, Flanders agreed to providing 62% and Wallonia 36% of the renewable energy required by 2020. Pointing to high costs of renewables in the city region, Brussels was able to get off lightly with only 2%.

This split makes the energy transition very dependent on what happens in Flanders and also Wallonia. Belgium also risks not meeting its renewables target in 2020 due to the recent decision by Flanders and Wallonia to no longer construct or subsidise large biomass power plants. The Walloon energy minister Jean-Luc Crucke points to several factors behind the decision, including tight budgets, long-term biomass supplies, energy efficiency and a "significant" doubt about the carbon neutrality of burning wood.

Other dampers to growth have been over-subsidising renewables and not just solar power. Walloon energy minister Crucke wants to stop the region's Qualiwatt subsidies for solar power at the end of June. Lower solar power costs and tight regional budgets are the major reasons.

But previous over-spending has given renewables financing a bad name, especially when it comes to major projects. Calculations by Belgium's energy regulator suggest that Belgium may have paid some €2 billion too much to support the Rentel and Norther offshore wind farms, when compared to support prices agreed to by the business-savvy Netherlands.

Overcompensation does not detract from progress in establishing clean energy. Renewables has grown from 2% of consumption in 2005 to 8% in 2014. Offshore wind has taken an increasing share of the cake in recent years. And Belgian — or Flemish ― offshore wind beat its production record on 22 October 2017 when enough electricity from the North Sea farms was generated to provide for the equivalent of 4 million households, or 38% of industrial electricity consumption.

| Flemish or Belgian wind? Have you been to the Belgian coast? Or is it the Flemish coast? For French-speakers, la côte Belge sounds totally natural, whereas more and more Dutch speakers speak of de Vlaamse kust. And the Flemish government even makes a point of only referring to the Flemish coast. Newcomers may laugh at such apparent pettiness. But even if renewable energy, such as offshore wind, is a Flemish competence, electricity and the North Sea are a federal matter. Therefore, should we speak of Flemish or Belgian offshore wind? And who should then pay for the investment? Those were some of the questions floating around as Belgian politicians set about deciding how to reach its EU target share of 15% renewables by 2020. This target, alongside the EU's general 20% target share, were set in law by the EU in 2009. But it took a further six years for squabbling Brussels, Flanders and Wallonia to finally agree on exactly how to share the hard work needed to push renewables. Squabbles like that have held up the transition to clean energy. |

By Dafydd ab Iago