Brussels would amount to relatively little without the arrival of migrants who have flocked here over many years. Migrants add colour to the culture and vibrancy of the city as well as substantially boosting its economic well-being. But very little has been done to formally record the impact migration has had on the city. That is, until now.

The MigratieMuseumMigration (MMM) opened in December 2019 in Molenbeek to tell the story of migration by migrants themselves. One message by a migrant called Daniel reads, “Get people with a migration background out of Brussels. What do you think is left over? Nothing…. empty streets and squares.”

The museum is a project of Foyer, a non-profit organization that was founded in 1969 as a youth centre. Also situated in Molenbeek, it is active at the local, regional and international levels, focusing on social cohesion and on the empowerment and integration of people with an immigrant background.

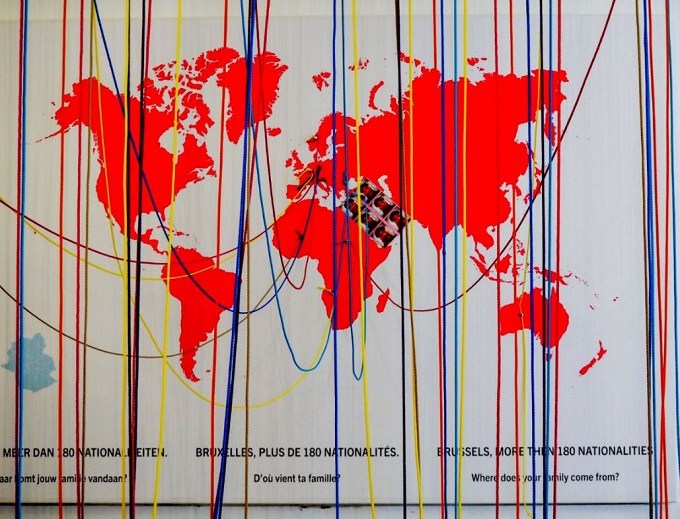

People who are born abroad constitute 16.4% of the Belgian population. Their proportion within the population varies significantly depending on region. 45% of those living in Brussels are immigrants, compared to 15% in Wallonia and 12% in Flanders. In the greater Brussels region, with its 1.2 million inhabitants, 60% of the population is born outside of Belgium.

VUB cultural philosopher Eric Corijn lays out some context to just how diverse Brussels is. “Expats and immigration have changed Belgium. Brussels went from being Belgian to a small world city: 61% of households are multilingual, 5% Dutch-speaking only and 33% French-speaking only.” The Flemish and French-speaking communities are minorities in their own capital.

The MigratieMuseumMigration (MMM) opened in December 2019 in Molenbeek.

“The major challenge is to bring communities together in a new idea of citizenship that puts the city before nationality, uniting in diversity.” This is a very clear message that should resonate with all.

The growing participation of Turkish, Moroccan, and Congolese first-generation migrants and their children in the federal, regional, and local political arenas demonstrates the influence of immigration on the Belgian political stage. Meyrem Almaci, current leader of the Flemish Green party, and Zakia Khattabi, leader of the francophone Green Party are notable examples, just like Zuhal Demir, Nahima Lanjri, Meyriame Ketir, and Yasmine Kherbache—all prominent parliament members.

A 2018 study found that, globally, a 10% increase in migrants from a specific country in a Belgian region led to an increase of 1.2% of the region’s exports to and 3.6% of its imports from the country in question. Migrants create a diverse labour force and increase trade with other countries thanks to their network connections. Societies are enriched with persons of all backgrounds.

The new museum wants to provide a permanent “home” to the stories of the first generation of what were called ‘guest workers’, followed by war refugees, asylum seekers, and Europeans and expats, who currently move freely within the EU. The stairwell displays a long list of the most common names of migrants while a digital screen shows the demographic evolution of the region.

On the first floor, the heart of the museum, the visitor will see two circles that are designed to radiate warmth and light. The various waves of migration to Brussels are explained on panels, while a touchscreen gives the visitor an overview of the demographic evolution of Brussels. Visitors can search by region or municipality and will also find the complete list of nationalities living in Brussels.

Personal memories, photos and souvenirs are central to the museum’s concept. One part, for example, displays the works on the migration theme of seven contemporary artists - Willem Boel, Peter Buggenhout, Ermias Kifleyesus, Charif Benhelima, Thomas Israel Elio Germani, and Elia Li Gioi.

In recent years, more and more people have arrived to Europe and Belgium via the Mediterranean, risking their lives in rickety boats in the hope of a better life in Europe. Some of them travel from Greece, Italy and Spain to Brussels. The exhibition "From Pain to Hope" by contemporary artist Elia Li Gioi depicts this current theme.

Li Gioi lives in Sicily and has been committed to social integration, literacy and the promotion of culture and solidarity for years. In recent years, he has seen people wash up on the beach with his own eyes. As a person and as an artist, he says he did not want to stand on the sidelines. He went to work with the material he found on the beach: life jackets, remains of boats with which people risked the perilous crossing, nails, survival material. This forms part of his exhibition at the museum.

The personal stories of some of the immigrants are recounted in 42 display cases, each highlighting an individual or a theme, and filled with photographs, documents and objects that, on the one hand, are very personal, but which, on the other hand, become universal because of their recognisability.

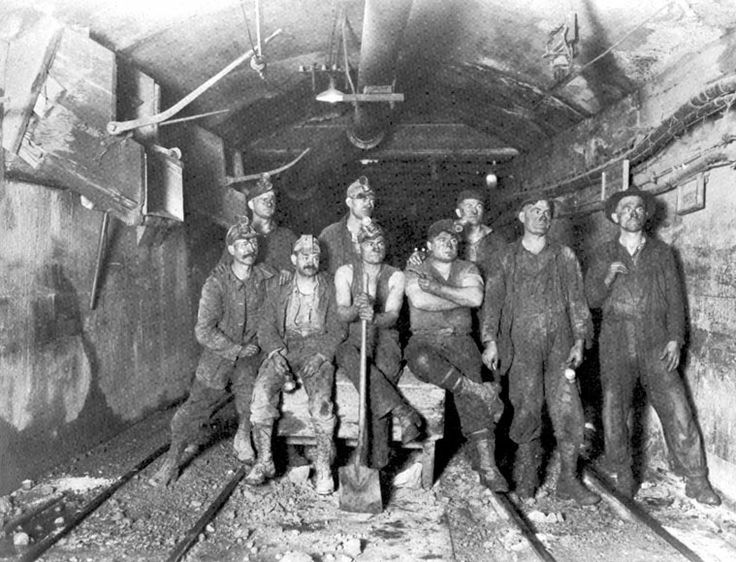

An example is a humble helmet. This inanimate object has little historical value, but it does evoke stories among an entire generation of men about the time they were excavating the Brussels metro tunnels. The same helmet also tells the story of the Polish, Bulgarian and Portuguese construction workers here today, and shows that Brussels was literally built by different generations of migrants.

Between the display cases are quotations that give more meaning to their content. “We consider each story special,” said a spokesperson of the museum. “The display cases are designed in such a way that they can easily be changed. In the future, we will certainly continue to look for more stories and hope that these unique and warm presentations will inspire many visitors to share their own story.”

Johan Leman, a professor of anthropology at the KU Leuven, is the president of Foyer. He said, "In the coming years, MMM will give a home to the narratives of the immigrants of the 184 nationalities that are part of the Brussels mosaic, also taking into account the gender aspect. MMM is migration museum, continuously evolving, much like the Brussels’ migration streams."

“In times in which populism and anti-migrant rhetoric are on the rise, this museum is a good contribution, as it helps us understand the complexities of migration, and sets up a more positive narrative on migration,” said Sara García de Blas, communications officer at the Brussels-based Jesuit Refugee Service Europe. “Moreover, the migration museum lets the migrants speak to tell their own story.”

A brief history of recent migration to Brussels

To fully appreciate the new museum, it helps to recall that Brussels has not become as diverse as it is today overnight. The first migrants to arrive after WWII were called ‘guest workers’, and their families came from the Mediterranean region.

After the war, Belgium was in ruins and its reconstruction required a great deal of energy and labour. In 1946, the Belgian government signed an agreement with the Italian government - manpower in exchange for coal. Thousands of Italians came to work in Belgian mines. It was dirty and dangerous work and their housing was of poor quality.

In 1956, a major mining disaster in Marcinelle, part of Charleroi, claimed the lives of 262 miners. The Italian government demanded better working and living conditions, and, after hesitation on the part of the Belgian government, Italy withdrew from the agreement. Belgium looked for new partner countries and an agreement was signed with Spain in 1956, and with Greece in 1957.

The golden years of the 1960s followed, and, in large cities such as Brussels, many major infrastructure works were carried out. The service economy also became increasingly important. From the mining regions, many families moved to the capital. Other labour migrants came directly to Brussels, and in 1964, similar “exchange” agreements were signed with Morocco and Turkey.

At the beginning of the 1970s, the energy crisis struck and the government announced a freeze on labour migration. But this did not mean the end of migration to Brussels, just an end to years of an influx of young, cheap, mainly male, labour from the Mediterranean region.

Family reunification remained an important part of legal migration in the coming years, while expatriates, residents of EU countries, students and asylum seekers were granted the right of residence. This evolution towards a “super-diverse Brussels” is all explained at the museum.

Its displays tell how, at the beginning of the 1980s, human mobility within and to Europe was fairly limited. Until 1985, asylum seekers were virtually absent from the public debate in Belgium. Local reception was provided by a private refugee network, while the Red Cross with the support of local public centres for social welfare took care of Hungarian refugees and the Vietnamese boat refugees.

In 1986, during an emergency meeting, the government in Belgium decided to open the Petit-Château, former military barracks in Brussels, as an asylum centre, and, in November 1986, an asylum seeker from Ghana was registered as the first resident in the Petit-Château. Over the years, the centre has taken care of more than 80,000 people.

Outbreaks of war and instability has led to a permanent influx of refugees with a number of peak periods, including the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989); the first crisis in the Balkans (1993), the second (2000); the conflicts in the Great Lakes region (2000); Iran (2000); Syria (2011); Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan (2015).

Adding to this has been the influx of people working at the EU institutions and international organisations such as NATO. The number of European civil servants rose from 300 in the 1950s to 40,000 today, for instance. The enlargement of the European Union in 2004 and 2007 also ensured the free movement of workers from the new member states in central and eastern Europe.

The museum is open daily, except for Sunday and Monday. Admission fee is €5.

Rue des Ateliers 17, 1080 Molenbeek

www.migratiemuseummigration.be

museum@foyer.be

By Martin Banks