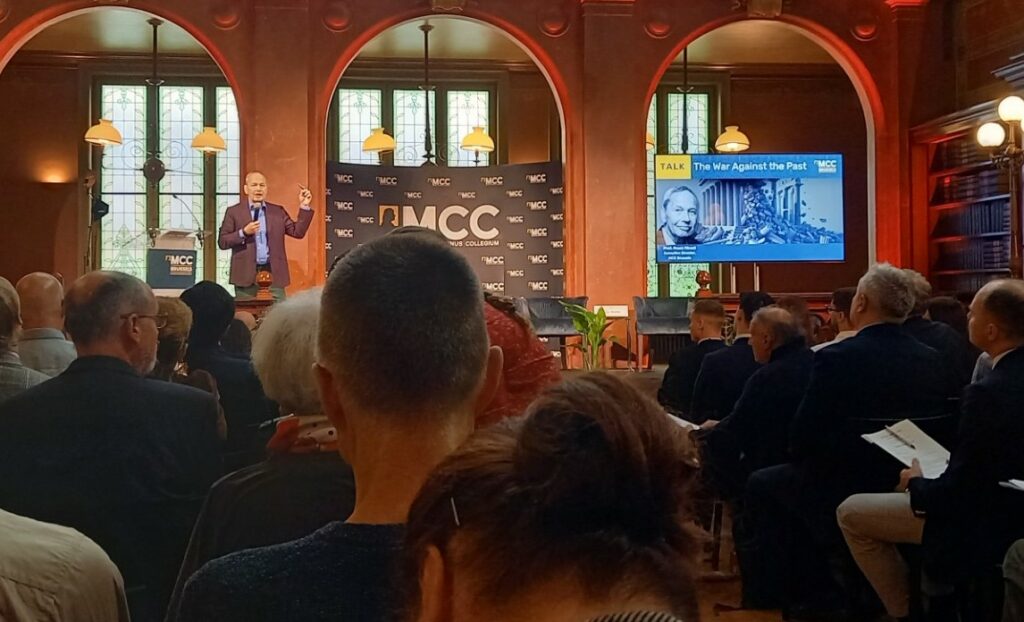

The EU’s concept of a common European history and the approach to history teaching was discussed at a recent seminar at Solvay Library in Brussels organized by the conservative think tank MCC Brussels.

The think tank, while independent, has close ties with Mathias Corvinus Collegium in Budapest (named after a Hungarian king) and the government. While promoting debate on a range of topics, MCC Brussels says that it believes in family values and national sovereignty. The seminar was devoted to the launch of a book by its executive director, Dr Frank Furedi.

Hi is a well-known former professor of sociology who also has studied history and wrote his thesis on the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya against British colonial rule. In his book, ‘The war against the Past: Why the West must fight for its history”, Furedi stresses the importance of reading and understanding history and puts it in a context of ‘culture war’.

According to Furedi, a narrative of national and historical shame has rewritten history in Western Europe. National heroes and accomplishments are dismissed and guilt has become the foundation of national identity. “The past offers us language and meaning which has devolved over times,” he summarized. “But it has been de-evaluated and doesn’t serve us any longer as a source of inspiration.”

He listed some reasons for concern. Without a sense of the past, young people will have difficulties in finding their identity. It will disrupt family bonds across generations. The disconnection from the past will also affect the future of our societies.

Learning from history

The academic group which designed The House of European History (next to Solvay Library) applied three criteria for the exhibitions in the new museum: the event or idea should have originated in Europe, expanded across Europe and continue to be relevant today. It focuses on European phenomena, including difficult or negative events, in contrast to museums in the EU member states that often have been designed to glorify the history of the nation.

Is this museum part of a culture war against history or does it complement national museums? “It’s constructing a myth about a common European history while the history of Europe is the history of nation states,” Frank Furedi replied. He regards The House of European History as a political project.

How do you strike a balance between remembering and teaching national history and critically reevaluating historical events and actors in the past when other values than today were prevalent?

“We should learn of the mistakes of history,” he replied. Asked about possible manipulation of Hungary’s own history in modern times, he described its history as complicated with different views about Admiral Miklos Horthy, who was the regent of Hungary during WWII and collaborated with Nazi Germany.

Furedi mentioned Niccolò Machiavelli, the Italian writer known for his book ‘The Prince’ with advice on how to govern a state. Machiavelli had studied the lessons of history. As a politician he mobilized a people’s army in Florence, instead of the usual mercenary armies of the time, to resist a French invasion of Italy at the end of the 15th century. He was an exponent of what we today call political realism.

Connecting with roots

One of the panels was about teaching history in schools. The starting point was that history lessons no longer teach pride in national heritage but rather guilt about e.g. European colonialism. Göran Adamson, a Swedish professor of sociology, known for his critic of multiculturalism, remembered with nostalgy his childhood with excursions to historical and nature sites. Today, schools are depriving pupils of their roots, he said.

Asked about the possibility of multiple identities, including a European identity, he replied that it is possible. “Certainly, you can have more than one identity, Swedish, Scandinavian, European etc., but one determines me much more - my national identity. Just think about it: how much in your life and your past goes back to your country?”

Events in the past can inspire us and make us feel pride but they can also disgust us and make us feel sorrow or guilt. Should history lessons also teach us about the mistakes in the past so that new generations won’t repeat them?

“History teaching should not be one long odyssey of insipid celebrations. We must also be modern and self-critical. On the other hand, every country has the right to lean towards a positive description of its national memory. We have all the right to get soft at heart at our old ancestors who fought for our country, not the least because we still are benefitting from their struggles.”

Sweden has been a relatively homogenous country for centuries, although divided by class, but there are still differences by dialect and county origin. MCC Brussels has just published a new book by Göran Adamson about the impact of mass immigration and multiculturalism on Sweden. Is there a risk that the book will be misused by the far-right in Sweden?

“I can't take responsibility for what others might say or write about my book,” he replied. “But if you read the book closely, you’ll realize that I’m critical in both directions: both against the multiculturalists and their hidden racism, but also against the far-right which idealizes their own culture. That said, I still find the nationalists' preference for their own country more understandable and natural.”

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times