“If there’s a war, I’ll fight,” he says. “For the Belgians?” “For anyone who’s against the Nazis.”

It is August 1939 in Ixelles. A young woman, Charlotte, opens the door to loud neighbours. We hear banging, read about the offering of buns and bread, and start to explore the world of a daughter and father in the ‘before’ times.

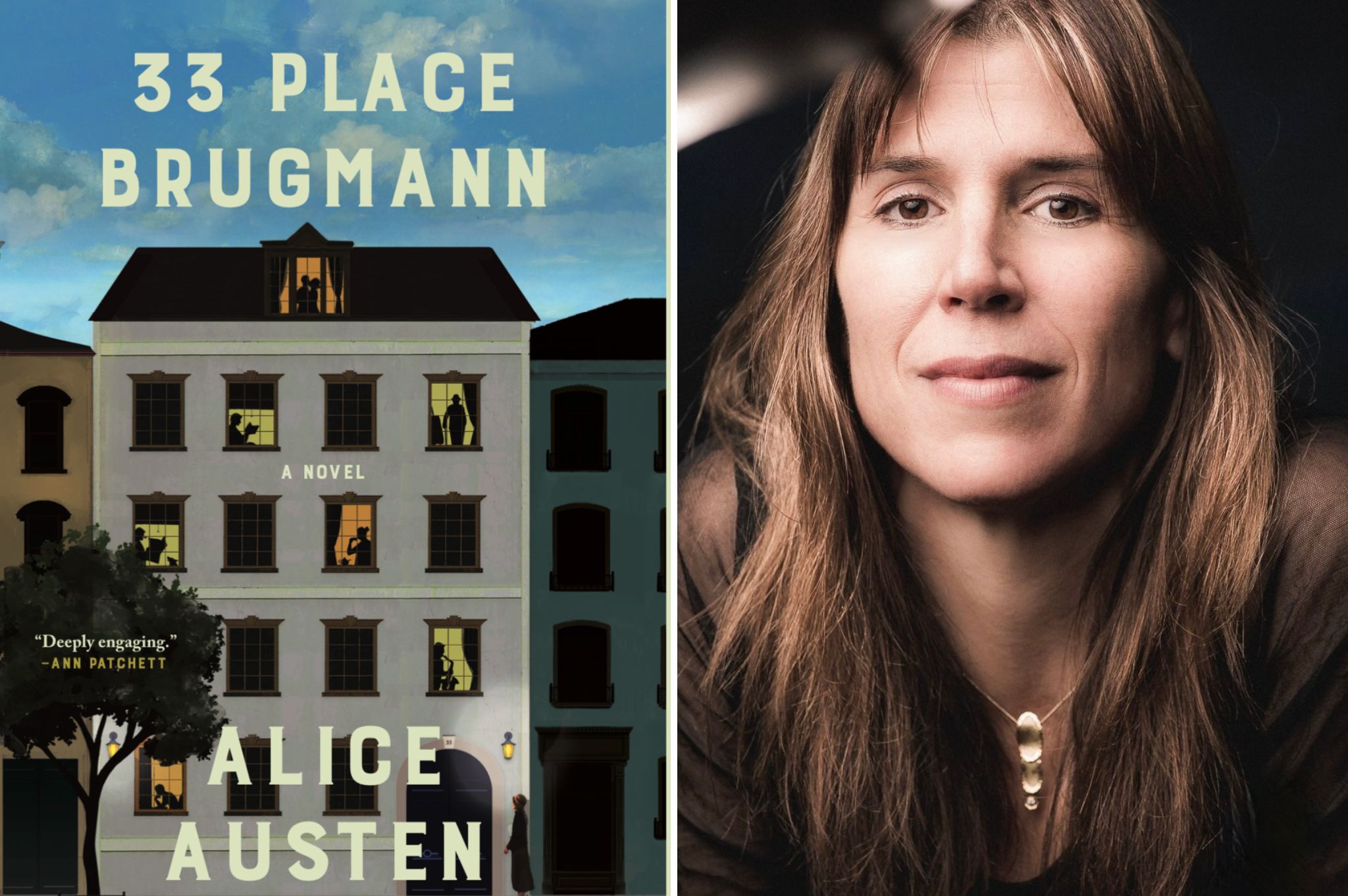

In the months before the Nazis invade Belgium, the scene is set in 33 Place Brugmann, the debut novel by American human rights lawyer and playwright Alice Austen.

Austen introduces us one-by-one to the characters who all live in a large apartment building in the eponymous square, from an art student and her father to an architect, from a dressmaker refugee to a Jewish art dealer with his family.

They are identified by their name and apartment number, and each life within these 14 apartments tells us more than history could. Each recounts their days, lives and loves as one does in an apartment building that is interconnected but not a community.

The book opens with a note from the fleeing Raphael family. “The Raphaels leave in the middle of the night, and they leave everything behind. The sofas and chairs and beds and lamps and heavy carpets and the dining table. The films we made are in a box together with the projector, a set of oil paints, and a blank canvas. On it is a note that reads For Charlotte.”

Photos of 33 Place Bruggman in Brussels today, the scene of Alice Austen's new novel. Credit: The Brussels Times

“I always knew I’d write this story,” Austen says. “It took time to figure out how.”

Initially, she considered adapting it as a play, but the constraints of modern theatre — limited budgets, small casts — pushed her to rethink the format. Ultimately, the novel form allowed her to explore the deep interior lives of her characters.

The novel’s urgency grew as she watched the world become increasingly polarised. “People have stopped talking,” she says. “That’s dangerous because when we stop communicating, ideology takes hold. People hold on to their ideas – they don’t allow them to be questioned, to be challenged. So it became very urgent for me to write about how we all live in neighbourhoods with people who have different ideas, and then what if you're dependent on your immediate neighbours for security or for food.”

Law and literature

Austen has many feathers in her cap. An award-winning screenwriter, producer and playwright, she is a Harvard Law School graduate and co-founded the Harvard Human Rights Journal. She was the first American to receive a fellowship to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg and as a lawyer, represented the Ministry of Industry in Václav Havel’s Czech government.

A writer for the acclaimed Chicago-based Steppenwolf Theatre Company, and a past resident at the Royal Court Theatre, her debut film Give Me Liberty, which she both wrote and produced in 2019, won a prize at the Independent Spirit Awards and was screened at the Cannes Film Festival. She is also working on movies with Oscar winners Alfonso Cuaron and Steven Soderbergh.

Austen started writing very young. At 13 she sent in a short story to a writing class given by Ken Kesey, the American author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. “So, there I was this 13-year-old writer. And he gave me a copy of The Dubliners, which I still have. And I’ve never really stopped writing.” She later studied under Irish poet Seamus Heaney at Harvard’s Creative Writing department.

Neighbours and narrative

Austen’s personal connection to the story is deeply rooted. She lived in the building at 33 Place Brugmann between 1990 and 1996 in what became Charlotte’s apartment in the book. “While I lived there, my eldest son was born, and my first play was produced. This was the 90s, and I had a colicky baby. You get to know people very quickly with a colicky baby,” she laughs, as she calls in from her cosy study in Wisconsin.

Place Brugmann is a spacious square in one of the chicest neighbourhoods in Ixelles, dominated by the brown-bricked church, Notre-Dame-de-l'Annonciation. Surrounding it are grand, Parisian-style apartment blocks, with cafés, restaurants, real estate office and boulangeries. As a building, 33 Place Brugmann has an imposing, impressive red brick facade, cream finishings with a dark slate, styled roof and a strange ornate metallic object sticking out of the façade like a pulley.

Place Georges Brugmann in Ixelles

Among her neighbours were two elderly women who had lived there since before the Nazi occupation. One had an extraordinary private art collection – an inspiration for the character of Raphael’s art collector in the novel. “They told me stories of what had happened in the building. And they were so funny! And heartbreaking and suspenseful! Everyone knew their neighbours were up to something, but no one knew exactly what.”

It sparked the idea of trying to capture that sense of mystery. “And that’s when I came upon the first-person perspectives of multiple narrators as a way of giving the reader that sense of suspense and not knowing,” Austen says. “I wanted to create that sense of uncertainty. You don’t always know what’s happening in your neighbour’s apartment, or what risks they might be taking.”

She initially grappled with the tone of the narrator and the voice. “I had a more omnipresent narrator, but it wouldn’t work. Then this idea came of seeing all the characters living there in the building and visualising each life taking place in each specific apartment. Then they started jumping out at me and became one by one their own voices.”

It took about a year and a half to write the book albeit following decades of searching for a way to tell the story.

Alongside the occupants she was inspired by a colleague who had been a resistance fighter, eventually became a British intelligence officer and was one of the architects of the European Union. “The connection between the war and the European Union struck me as also very powerful. Especially in light of today,” she says.

City as a character

Brussels is often overlooked in historical fiction, but it provides a vivid setting for Austen’s novel. “I think people were delighted to hear a story that was fresh,” she says.

She was particularly struck by stories of the Belgian resistance, including the Comet Line that smuggled stranded Allied pilots out to safety. “When you think of the Comet Line, and how heroic many of these very young women who organised it were and how they risked their lives to escort many people and RAF fighters – it was just extraordinary,” she says. “Some of these women, including the founder of the Comet Line, were in concentration camps and they were betrayed. They were so valiant and little bits of that story figure into this as well.”

A woman buying bread on the black market Brussels folk during the Second World War in 1943.

The Nazis had many cruel methods to control the local population. One way was to weaponise food and hunger. “When I began to research, I found that Belgians lost, on average, six kilos per person the first year of the occupation. So they really had a scarcity of food,” she says. “In a situation where you don't have enough food for your family, evil regimes use those things. You get food if you give information.”

Some tried to leave, but most could not. “Then the question is what do you do and how do you behave?” Austin says.

Tragedy foretold

Austen is clear that today’s global environment has echoes in the pre-war era, with war raging on Europe’s edge, authoritarianism on the rise and fascist language seeping into discourse – and she sees US President Donald Trump as a would-be dictator in the 1930s mould.

In the book, lines pack a punch, with one character saying, “Not everyone here is persuaded that Hitler is a monster,” and discussions of where the bombs would fall in Brussels, (the Grand Place perhaps, a character asks).

“I think we are in a time of great fear, of people feeling threatened,” she says. “And anxious. And people not communicating. All you have to do is look at history to know how dangerous that combination is.”

Austen’s background also played a role in shaping the book: her mother is a painter and she grew up with an appreciation for visual storytelling and mise en scène.

She also grew up with a sense that there wasn’t a war in recent memory in America. “The characters can look back in their rear-view mirror and see World War I. Some of them are in denial: ‘No, no, it’s all alright.’ And that’s what we do we tell ourselves, ‘No, it’s all alright, it won’t happen again.’”

Although the neighbours turn on each other, Austen describes how she fell in love with her characters. As she wrote she had a certain idea about them and really tried to walk in their shoes. “My characters surprised me often, and there’s a sense of surprise in the narrative,” she says.

Foreboding

Austen’s legal background helped her understanding of history and moral dilemmas: not just at the ECHR but working with the Czech Republic as they transitioned from communism, experiences that sharpened her awareness of how societies reconstruct themselves after trauma.

Nonetheless, she could not have anticipated just how timely her novel would feel in a world where extremism is on the rise, war has returned to Europe, and dissent is being silenced.

Cover in French of 33 Place Brugmann – a new book by Alice Austen, which follows the lives of 14 families in one Brussels building during WW2

“At the time I started writing this, I didn’t think it was going to happen,” she says. “Now I talk to people, and they say, ‘Oh my God, this book feels so timely.’ As a writer, it is terrifying to write about one of the worst times in modern history and have people say this. And tragically it does feel timely – especially given what’s going on in the US right now. At the time I lived in Brussels, everything was so hopeful, the future of the West was brilliant and democratic, and it is not that time now, and I think a lot of people are concerned.”

As the literary world faces challenges – book bans, censorship, ideological battles – Austen remains steadfast in her belief in the power of literature and reading. She says banning books is a hallmark of authoritarianism. “Anybody who proposes bans and at the same time professes to be trying to bring America back to the founding fathers is fundamentally at odds with the values of the country,” she says. “It makes no sense. The whole thing is just crazy. You see the burning and banning of books under almost every fascistic regime. Voltaire's books were burned by the king. It's happened over and over in history because ideas are dangerous to people who want everyone to follow their idea.”