To outward appearance, the herbarium at the Meise Botanic Garden is botany at its most sterile: metre after metre of linoleum and steel. It is a sequence of vast rooms containing row after towering row of steel cupboards, alleviated only by a few display cabinets. Behind the steel, however, is an astonishing treasure of science and the history of science.

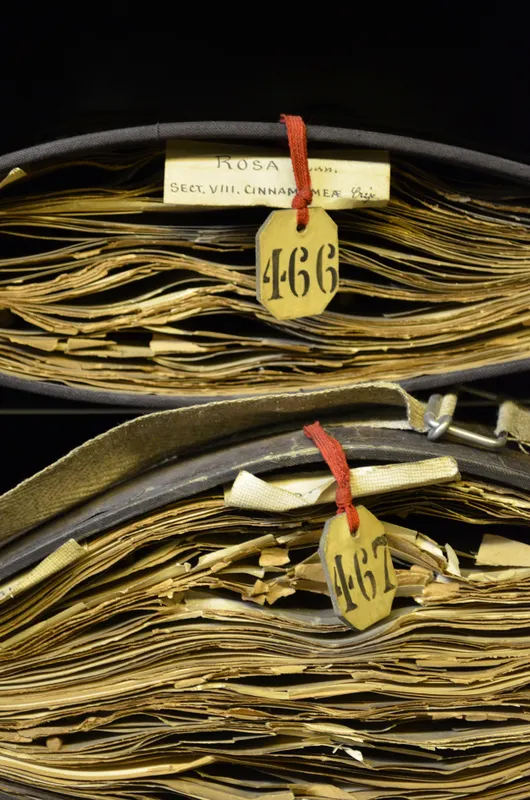

Koen Es, the Director of Public Services at Meise, opens up one of the steel cupboards, to show me a sequence of shelves stacked with piles of folders. “Our collection is arranged alphabetically by genus and within each genus alphabetically by species. That way, if a species gets reclassified, we don’t have to move the whole genus,” he says.

You sense it must happen: on the other side of the globe, a post-doctoral researcher using modern DNA technology creates a tectonic shift in herbariums across the world.

Each folder represents a plant species. Inside each folder are wallets containing pressed dried plants, drawings and descriptions. Mostly, the descriptions are in Latin, because that is the dominant language of botany. It was only in 2011 that the International Botanical Congress relaxed the Latin requirement, permitting description either in Latin or English (the first-ever meeting of the IBC was in Brussels in 1864).

The goal of its rigorous international classification system remains pretty well what it was in the 18th century when Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish naturalist, laid down his system of taxonomy: that identification should be systematic and that a species should have only one name, accepted across the world.

Seed secrets

On the shelves of the Meise herbarium, most of the folders are white, but some folders are pink, to indicate that they contain the “type specimen”, that is, the specimen that first identified that species. The Meise herbarium contains 40,000 type specimens, in a collection of approximately four million items. Its particular strengths are the plants of central Africa, Latin America and Belgium.

Linnaeus’s herbarium, the basis of his masterwork, Species Plantarum, contained 19,000 dried and mounted plants. On the death of his son, it was bought by an Englishman, James Edward Smith, much to the irritation of Sweden’s King Gustav, who tried to prevent its export, and Catherine the Great of Russia, who had also wanted to buy it.

Line of continuity

The Meise herbarium too began as a compilation of personal collections. Barthélemy Dumortier was both a botanist and a Belgian politician: he was the first to observe and describe cell division, published a Flora Belgica in 1827, and for nearly 50 years was a member of the national parliament from its creation in 1831.

He became the first president of the Société royale de botanique de Belgique/Koninklijke Belgische Botanische Vereniging (SRBB/KBBV) when it was created in 1862 and he persuaded the parliament first to buy for the state the herbarium of Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, a German explorer and botanist, and then, a few months later, to buy the Brussels botanic garden.

Von Martius, who was keeper of the botanic garden at Munich, had compiled a description of all known members of the palm family and oversaw the compilation of Flora Brasiliensis. At his death in 1768, his herbarium had 300,000 specimens, one of the largest personal collections in the world.

Seed secrets

To look inside those folders at the drawings, the pressed plant material and the Latin descriptions, is to see a line of continuity that extends back at least to the 18th century and the era of Linnaeus, taking in the likes of Joseph Banks, the pioneering English naturalist who transformed London’s botanical garden at Kew so that a century later it was the model that Dumortier wanted to copy.

While still in his twenties, Banks travelled to Newfoundland and Labrador in 1766 and to the South Pacific in 1768-71, visiting Brazil, Tahiti, New Zealand and Australia, and recording his botanical findings according to Linnean principles. It was into herbariums that Linnaeus and Banks and their botanist successors poured the wealth of their discoveries.

They made their collections available to other botanists and they built up their collections by gifts and exchanges. Those herbariums were repositories of data in the information network of a pre-internet age. And now their treasures are being opened up by digitisation.