Today marks the 40th anniversary of one of the darkest days in Belgium’s postwar history.

29 May 1985 was a balmy spring day in Brussels, and that evening's match between Juventus and Liverpool at the city's Heysel stadium offered so much promise.

It was supposed to be European football’s showpiece event - a European cup final bringing together two of the continent’s most venerable clubs. Speaking to the Guardian in 2015, Juventus fan Bruno Guarani recalled the joy he felt on the plane journey to Brussels from Italy with his son Alberto, as they anticipated watching the match together.

“Of course Alberto knew Liverpool,” Guarini said. “They were famous, a wonderful team and we thought the fans would be like us, just crazy about football.”

“Alberto and I had flown to Brussels together singing on the plane. And I flew back with the body of my son.” Alberto was one of 39 people – 32 Italians, four Belgians, one Irish and two French - to die that night. A further 600 people were injured.

At around 19:00, before the game kicked off, fans began confronting each other, throwing bottles, flares and stones. In the stadium, a group of Liverpool fans stormed the nominally neutral section containing large numbers of Juventus supporters, causing a panic.

As the Liverpool fans charged, some Juventus supporters were crushed against a crumbling stadium wall. The structure subsequently collapsed, leading to many of the fatalities. According to Guarini, who had moved towards the wall to escape the rival fans, his son’s last words were Papa, mi stanno schiacciando – ‘Daddy they’re crushing me’.

Amid the carnage, and despite protests from players, the match went ahead at UEFA’s insistence. Juventus captain Michel Platini lifted the cup after securing a 1-0 victory over Liverpool through a contentious penalty.

The immediate aftermath

The terrible scenes of violence in Belgium reinforced perceptions that the English game was rife with hooliganism.

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the blame was laid entirely on Liverpool fans. On 30 May, 1985, UEFA’s chief observer, Gunter Schneider, said: “Only the English fans were responsible. Of that there is no doubt.” UEFA subsequently imposed a ban on all English clubs participating in European competitions, only lifting it in 1990.

Liverpool carried the shame of what happened for many years to come. Mark Lawrenson, who played for the club on the night of the disaster, said: “As players, for whatever reason, we all felt guilty. At the airport the next day, we got spat upon. Even the bus that took us there was surrounded by very irate Juventus fans. We all just wanted to get out of the country.”

The British government took steps to mitigate the diplomatic fallout. Queen Elizabeth II issued formal apologies to the people of Belgium and Italy, while British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared “war” on football hooligans.

British and Belgian police officers spent hours trawling through photographs and footage of the violence to identify perpetrators. Chris Rowland, who wrote a book on the Heysel tragedy, said that in the following weeks, “you couldn’t pick up a newspaper or switch on the TV without seeing a circled 'wanted' face".

34 arrests were made back in Britain, but only 26 people were extradited to Belgium. Out of those convicted, 14 Liverpool fans were given three-year sentences for manslaughter, half of which were suspended.

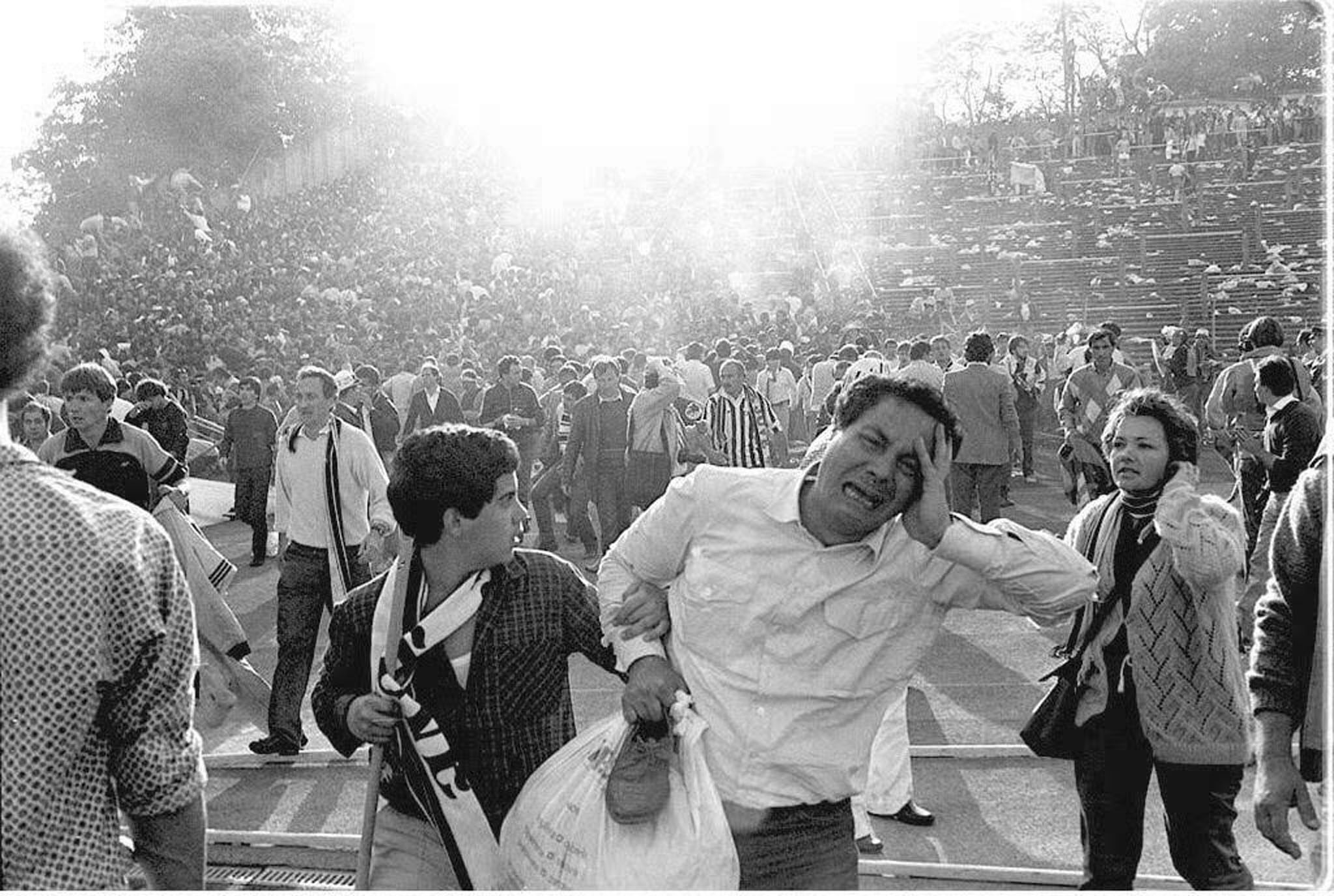

File picture taken on May 29th 1985 at the Heysel stadium in Brussels. Credit: Belga

The Coppieters Report

If Heysel triggered a shakeup in English football culture, in Belgium, it unleashed a wider reckoning.

A report by Belgian judge Marina Coppieters, based on a painstaking 18-month investigation into the events leading up to the disaster, concluded it was wrong to simply blame the fans for what happened.

The Coppieters Report, published in November 1986, said culpability also rested with the police and football authorities.

First, the stadium itself, which was built in the 1920s, was judged to have been unsafe to host a game of such magnitude. In the build-up to the match, numerous concerns had been raised about its decaying state. Liverpool’s secretary Peter Robinson is said to have urgently requested that UEFA move the final to a more suitable and safer venue, but his plea was ignored.

Surveying the stadium after the match, Belgian architect Joseph Ange said parts of the stadium were in an “advanced state of decay”. He noted that in Block Z, where the crush took place, “the handrails were quickly and easily destroyed by the pressure of the crowds, which had no proper means of escape”. An official report by the Belgian government assessed that eight out of 18 Belgian stadiums did not meet safety standards.

Judge Coppieters also criticised the ticketing arrangements for the match at Heysel. Liverpool fans were assigned tickets in Blocks X and Y, while Juventus fans were assigned tickets in Blocks M, N and O.

Tickets for Block Z, which was immediately adjacent to Block X, were nominally reserved for neutral Belgian fans, in theory creating a buffer zone between fans. In practice, however, a large number of ‘neutral’ tickets came into the hands of Juventus fans.

Five thousand ‘neutral’ tickets were put on open sale in Brussels, and were largely bought up by members of the city’s large Italian community. Despite the obvious danger this situation presented, there was no obvious attempt by the police to create a buffer zone between rival fans in Blocks X and Z, with only a flimsy wire fence separating them.

The policing operation left a lot to be desired. Out of 1,000 police on duty that night, just 72 were present in the stadium, and it took nearly an hour after trouble started for reinforcements to arrive.

Police captain Johan Mahieu, who was in charge of security at Heysel stadium on the night of 29 May 1985, was eventually charged with involuntary manslaughter on the basis of Judge Coppieter’s findings. He was handed a three-month suspended sentence.

But it wasn’t just police and football authorities who came under the spotlight in Belgium. The tragedy also unleashed political turmoil in the Belgian parliament.

A parliamentary enquiry released in July 1985 was fiercely critical of the Belgian authorities, and many expected senior ministers to resign in response to its conclusions. Unedifying scenes of buck-passing and blame-shifting followed, as Justice Minister Jean Gol called on Interior Minister Charles Ferdinand Nothomb to step down – which Nothomb declined to do.

In the end, nobody in the Belgian government resigned over Heysel, though Northomb’s intransigence played a role in bringing down Wilfred Martens' government in October that year.

An uneasy legacy

Despite the manifold safety concerns raised over structure of the Heysel stadium, it continued to host football matches even after the disaster took place. From 1986 to 1990, Heysel was used for Belgian international games. It was only when UEFA imposed a 10-year ban on Belgium hosting European finals that the authorities finally decided to stop playing matches there.

In 1995, the ground was rebuilt and renamed the King Baudouin Stadium, with only a small part of the original stadium remaining.

As for the two clubs at the centre of the tragedy, it has taken many years of soul-searching for them to start coming to terms with what happened on May 29th, 1985. Four years after Heysel, 97 Liverpool supporters lost their lives in a stadium crush at Sheffield Wednesday’s Hillsborough stadium. This led to a decades-long pursuit for justice as a series of failures by the authorities were exposed.

But Heysel remained something of a taboo subject. It was only in 2005 when Liverpool drew Juventus in a Champions League match that issues that had remained unspoken for years finally came to the fore.

Juventus supporter pictured during a tribute ceremony for the 30th anniversary of the Heysel stadium disaster. Credit: Belga/Dirk Waem

In the match at Anfield, Liverpool fans held cards spelling the word ‘Amicizia’ (friendship). The gesture was applauded by some Juventus fans, but others turned their backs.

This year, Juventus will unveil a new plaque in Turin to mark the 40th anniversary of the tragedy. It is called ‘Verso Altrove’ (Towards Beyond). The unveiling ceremony will be attended by Ian Rush – a player who played for both Liverpool and Juventus in the 1980s.

Earlier this month, Liverpool also announced plans for a new memorial at Anfield. It will feature two scarves knotted together – intended to symbolise “the unity and solidarity between the two clubs formed through shared grief and mutual respect”.

In Brussels, meanwhile, the city is making efforts to commemorate the tragedy. Today, there will be a ceremony held at the King Baudouin stadium honouring the fans who died.

To coincide with the 40th anniversary, Belgian filmmakers Christophe Hermans and Boris Tilquin produced a documentary for RTBF called 'Heysel 1985 - Dans l'enfer de la foule', drawing on archive footage and first-hand interviews with people who were there.