Woody Allen is synonymous with New York, Federico Fellini loved Rome while Jean-Luc Godard is indelibly linked with Paris. For Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, two-time winners of the Palme d’Or and recipients of yet another gong at the Cannes Film Festival in May, nowhere compares with Seraing, an industrial suburb on the outskirts of Liège.

Nearly all their films have been shot amid its gritty surroundings on the banks of the River Meuse.

However, for our meeting on the eve of the renowned festival on the Côte d'Azur, where their latest work, Jeunes Mères (The Young Mother’s Home), won the prize for Best Screenplay, the brothers have opted to save Seraing for celluloid.

Instead, they’ve invited The Brussels Times Magazine to an upscale hotel, just around the corner from our office. Decked out in Louis XV-style period furnishing and décor, it feels a long way, in every way, from their trademark, bleak but compelling depictions of life in left-behind communities, brilliantly captured on hand-held cameras.

Their uncompromising output has earned them epithets such as the ‘Brothers Grim’ and ‘Masters of Misery’ in the past, but in person, the Dardennes are warm and affable.

As I’m ushered into the small room chosen for our tête-à-tête, the pair are sat upright, almost perfectly symmetrical at either end of a firm-backed reproduction sofa. Sporting smart, open-necked shirts and neatly pressed slacks, they smile in unison. For a moment, I feel like I’ve just stepped into a Wes Anderson set.

Jean-Pierre, the older of the pair at 74 (no, they’re not twins), stands up and proffers a friendly hand, inviting me to sit opposite. His brother Luc, 71, follows suit.

While the idea is to talk predominantly about Jeunes Mères – of which I’ve already had a sneak preview – the conversation opens up to cover their early days, influences and views on various topics. More about the new film in a moment, but let’s start at the start.

Jeunes Meres (2025) by Dardenne Brothers

Both were born in the province of Liège, Jean-Pierre in Engis in April 1951 and his younger brother in Awirs in March 1954. They also have two sisters, Marie-Claire and Bernadette.

I ask if their parents, Lucien and Marie-Josée, influenced their career path and the themes of struggle and marginalisation that they frequently address.

“Yes, definitely,” says Luc. “Our family home was very open to everyone, especially poorer neighbours who would come to eat with us. Our father was a member of a Christian social movement, St Vincent de Paul, and he actively helped the poor in the village and the industrial suburbs. Our mother was also very, very open.

“It wasn’t a big house. But there was enough food and, if neighbours were hungry, our parents would say, ‘Come on, sit down and eat with us.’ I remember one day my father took in a kid from a very poor family. He stayed with us for a few days and washed in the same bathtub. I was four or five years old, and he was seven or eight. That’s how it was.”

If Lucien Dardenne, who died aged 98 in Engis last November, was responsible for imbuing his children with a sense of social responsibility, their artistic side certainly came from their mother Marie-Josée, who also lived into her nineties and passed away in 2017.

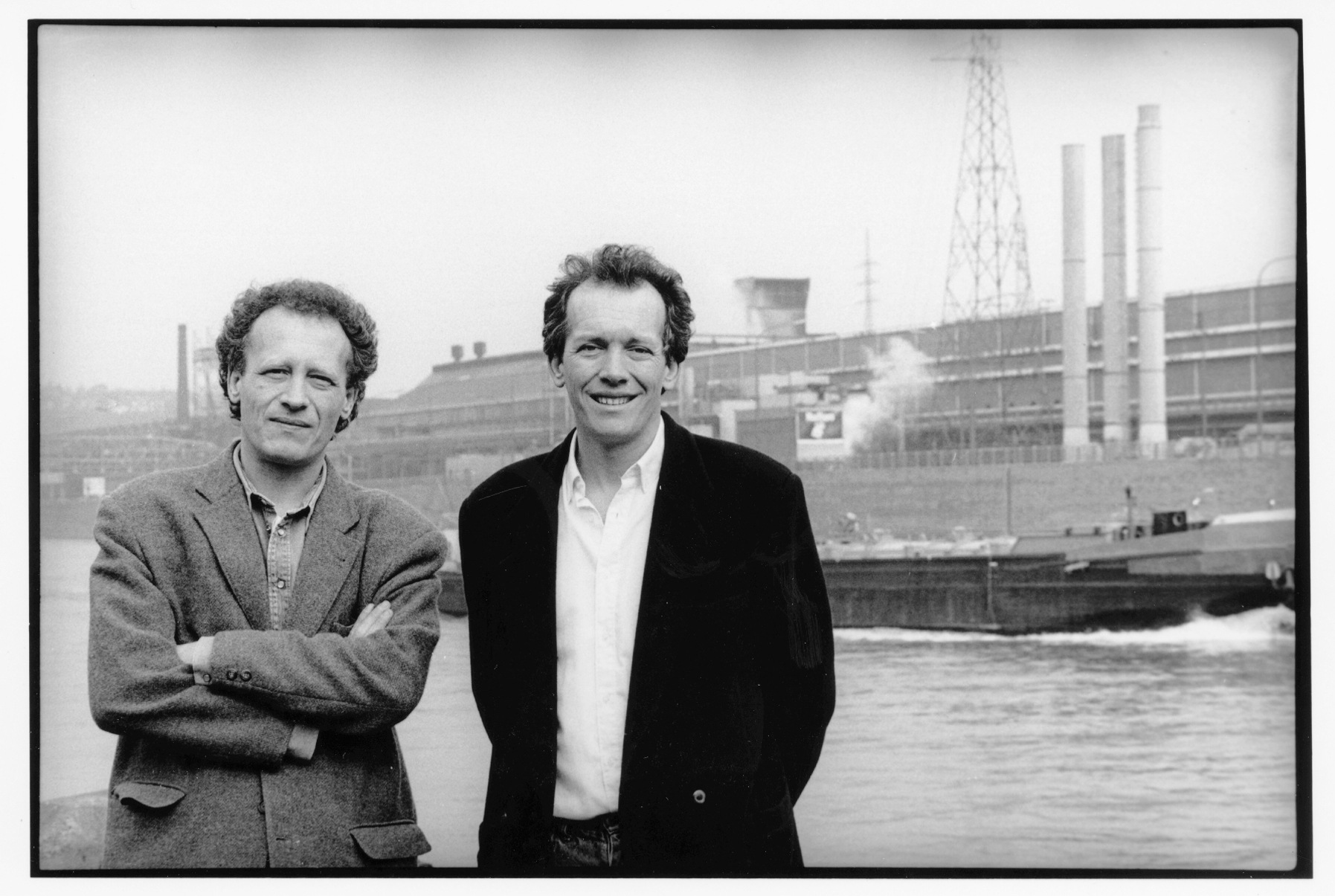

The Dardenne brothers in their younger years

“When she was young, our mum played in the village theatre troupe and she loved to sing and dance,” says Jean-Pierre. “After she became a mother, she took care of us and the troupe no longer existed. She always regretted that. I remember when we were little, she’d sit the four of us down and disappear behind the door. She’d come back in a costume and sing and dance, then disappear again before returning in another disguise.”

After completing secondary school, Jean-Pierre enrolled at the Institut des Arts de Diffusion (Institute for Broadcasting Arts) in Brussels, where he studied drama under Armand Gatti, a much-travelled playwright, filmmaker and former wartime Resistance fighter.

Luc initially studied philosophy and sociology but joined his brother as an assistant to Gatti, who encouraged them to make their first forays into film, shooting in working-class areas of Wallonia.

They made a series of politically engaged TV documentaries in the 1970s, founding their own production company, Dérives, in 1975. They released their first feature film, Falsch, in 1987. Based on a play about the last survivor of a Jewish family exterminated by the Nazis, it is rarely shown now. However, it marked a career turning point as the Dardennes shifted from fact-based documentaries to making fictional works, albeit always rooted in compassionate social realism.

They attracted significant financial backing for their second feature, Je Pense à Vous, but it failed to have the impact they hoped for. Undeterred, in 1994 they formed a new production company, Les Films du Fleuve.

They were finally discovered by international audiences two years later when their third film, La Promesse, was screened during La Quinzaine (Directors’ Fortnight), the platform for indie films at Cannes. Starring 15-year-old, Brussels-born, Jérémie Renier, who would become a regular collaborator, it attracted glowing reviews worldwide.

Promess (1996) by Dardenne Brothers

Two become one

By this point, the brothers had established a modus operandi which has served them well ever since.

Jean-Pierre describes their routine: “When we start working, it’s always just the two of us. We develop a character or characters, then a structure with bullet points. Once we have a beginning, the different stages and an end, sometimes there are little scenes that we sketch out between us to create the beginnings of the dialogue. At that point, Luc writes the script.

“As he moves forward with it, he’ll call me regularly (Jean-Pierre still lives near Liège while Luc is based in Brussels) and send over what he’s done. We do everything else together.

“When we start working on the casting, rehearsals, location scouting and so on, we become one person in a certain way. There’s not really a strict division of tasks. We're not site managers,” he smiles.

But while two become one this does not mean they duck their individual responsibilities, says Luc. “When we face an obstacle, we never say to ourselves, ‘I don't care, my brother will take care of it’. Even when it’s the two of us, there are moments when we find ourselves alone.”

Tour-de-force

In 1999 the Dardennes won their first – and Belgium’s first – Palme d’Or, the top prize at Cannes, with Rosetta, featuring a tour-de-force performance by 17-year-old newcomer Émilie Dequenne, which earned her the Best Actress award.

Tragically, Dequenne died from a rare form of cancer in March this year, aged just 43. Jean-Pierre shakes his head. “She was young, so very young. The medicine was powerless to cure Émilie…”

“She was magnificent,” adds Luc. “A beautiful and good person. And such a good actress. It was always easy to work with her.”

Their nine films since Rosetta have all been screened in competition at Cannes, consistently winning accolades from the jury and plaudits from critics.

Jean Pierre and Luc Dardenne at work. Credit: Christine Plenus

The follow-up, Le Fils (The Son), earned Olivier Gourmet the Best Actor award, while the directing duo won their second Palme d’Or with L’Enfant (The Child) in 2005, joining an illustrious group who have done the double including Francis Ford Coppola, Ken Loach, Michael Haneke and Ruben Östlund. No one has yet clinched the top prize three times.

The brothers are often compared with Loach due to the issues they explore. “We don’t do exactly the same thing, but it’s true that we look at the social and economic conditions of individuals who are fighting to escape from their situation,” says Luc.

The pair are avowed Loach fans and vice-versa. They have backed several of the British veteran films including Looking for Eric, starring Manchester United legend Eric Cantona, and The Angel's Share, as well as 2016 Palme d’Or winner, I, Daniel Blake, the story of a middle-aged man denied sickness benefit by a harsh bureaucracy. “We’re co-producers with Sixteen Films, the company Ken runs with [long-time collaborator] Rebecca O’Brien,” says Jean-Pierre. “We’ve provided four or five Belgian technicians for his films.”

Matt Damon

The commercial success of L’Enfant and its follow-up Le Silence de Lorna – each took more than €5 million at the box office – meant the Dardennes were increasingly able to look to attract higher-profile actors.

Cécile de France had just finished shooting on Clint Eastwood’s supernatural thriller Hereafter with Matt Damon when the brothers cast her as hairdresser Samantha in 2011’s Le Gamin au vélo (The Kid With A Bike). “When the Dardennes or Eastwood call you, you say yes right away,” the Namur-born actress said at the time.

Her co-star Damon was keen to sign up with the brothers, too.

“Cécile told us he wanted to act with us,” recalls Jean-Pierre. “We kept it quiet, but we wrote a script in which he’s an American police officer who comes over to train the Belgian police. There’s a serious incident and he stays to lead the investigation.”

Rather fittingly for the Dardennes, there was no happy ending. “We never heard from him again,” sighs Jean-Pierre.

The brothers instead set their sights on enlisting La Vie En Rose Oscar winner Marion Cotillard in their next movie, 2014’s Deux Jours, Une Nuit (Two Days, One Night).

Marion Cottilard in Two Days, One Night, which is about long-term illness and work.

The French star was, in her own words, “overwhelmed with joy” when the brothers cast her as a working-class mum. And as a long-term fan of the Dardennes, she was thrilled when she learnt that the filming would take place in their customary base. “I wanted to go to Seraing, and I went to Seraing,” she declared.

The Dardennes returned to Cannes in 2016 with La Fille inconnue (The Unknown Girl), a whodunnit with French actress Adèle Haenel in the central role, then again three years later with Le Jeune Ahmed (The Young Ahmed), which starred debutant Idir Ben Addi as a radicalised teenager and won the Scenography Prize.

First taboos

Their 2022 film Tori et Lokita, a hard-hitting story of a migrant who finds herself trapped when the state denies her the papers she needs to live and work freely in Belgium, earned yet another award at Cannes. As usual, it was shot around Seraing and Liège.

I ask if the location to which they are so regularly drawn is an artistic choice or down to more prosaic reasons such as a desire to keep within budgets.

“It’s because it’s the area where we spent our childhood and adolescence, where we broke our first taboos,” says Jean-Pierre. “Back then it was a very industrial region with a lot of wealth and a lot of people, and suddenly all that just disappeared. We’d left to study and when we came back, we said to ourselves, ‘Shit, what happened?’ It’s as if these places were saying, ‘Hey, guys, why don't you tell stories in our country, in the area where you spent your teenage years?’

“We don’t only film in places which had a rich past and became impoverished. But, as the region of our childhood and adolescence, that’s a strong link.”

Jeunes mères

They started making Jeunes Mères in April last year. For once, the film is not set in Seraing, but all of 11km away in Alleur, where the Dardennes were inspired by the work of a real-life maternity shelter which provides support for underage mothers.

It’s clear that, while continuing their signature stripped-down style, they were keen to try elements of a new, more spontaneous approach. Jean-Pierre points out that there is “more optimism” in the story which follows five teenage mums and how they attempt to free themselves from “a destiny imposed on them.”

Jeunes Meres (2025) by Dardenne Brothers

They started their process by spending time in the maternity home where they would eventually shoot, talking with the young single mothers, most of them minors, as well as with the educators and psychologist. They say they were immediately drawn to the communal life: the meals, the baths given to the babies, the discussions about topics related to motherhood, violence and addiction. And while they saw moments of shared life, there was also loneliness, anxiety and inevitable questions about absent fathers.

The brothers received more than 300 CVs before looking at around 150 candidates for the five main roles. I ask how they pinned down their final choices.

“There are two things we’re looking for,” says Jean-Pierre. “Good actresses …and silence.”

If that sounds like a puzzling contradiction, he explains. “First, we have to think they’re going to be good at depicting the characters,” he says. “We do a little exercise. In this case, we did the first scene of the film in a simplified way. We play a woman getting off the bus, who Jessica [one of the young mums] comes to question. Second, we look for their ability to hold a silence. If there’s a moment before she speaks and before we turn around, we say to ourselves, ‘There’s someone who resists us, who knows how to create silences. She’s a possible.’ You then tell them, ‘Leave a little more silence,’ and we redo the scene and they leave a little more. That’s what we’re after.”

The Dardennes are known for putting their often young and inexperienced casts through demanding rehearsals before the cameras roll. “Their standards are total, unrivalled and unequalled,” said Marion Cotillard after making Deux Jours, Une Nuit.

Intuition

Unlike most of their films, Jeunes Mères does not focus on one or two characters. Originally the plan was to do that but after visiting the maternity home, the brothers felt they should broaden the storyline.

“We sensed sadness and tragedy there, but there was also life, tenderness and sweetness,” says Luc. “On the way back in the car, we said to ourselves, ‘Maybe we could do something with the setting and the group’. We started with two or three stories, then we thought we could tell another one – and ended up with five.

“Six might have been too many,” he concedes. “There really isn't an objective reason for going with five, it’s really down to intuition.”

That intuition never seems to fail them.

Jeunes Meres (2025) by Dardenne Brothers

I’m curious, however, why noisy buses and roads feature so often in their films. Is this a metaphor for the bumpy journeys their characters are on?

Jean-Pierre chuckles before replying. “A few years ago, we were in Seoul in South Korea to present a film in a theatre packed with young people. After a discussion with the audience, one of them raises his hand and, like you, observes that there are a lot of buses in our films. He asks, ‘Is that product placement, do you get paid for filming buses?’

“Of course, the answer is no. It’s simply because, in our region, everyone travels by bus. They’re everywhere, all the time. The buses are our equivalent of New York taxis. We actually have a new tram service in Liège so maybe we’ll put them on the tram in future, too!”

Mutual appreciation

Before calling it a wrap, I finish by asking the brothers about their competition in Belgium and whose work they most admire.

Both immediately highlight Lukas Dhont, the Gent-born 33-year-old director of Girl and Close, which starred Émilie Dequenne and shared the Grand Prix, the runners-up award at Cannes, with Claire Denis’s Stars At Noon in 2022.

The appreciation is mutual: Jeunes Mères is co-produced by The Reunion, the film company owned by Lukas and his brother Michael. It also received support from the Flanders Audiovisual Fund (Vlaams Audiovisueel Fonds, or VAF for short), among others.

As for Belgian actors, the brothers reel off the names of three of their regular collaborators: Jérémy Régnier, Fabrice Rongione and Olivier Gourmet. Jean-Pierre also highlights Jef Jacobs, a Flemish newcomer who plays Dylan, the father of Julie’s baby in Jeunes Mères, before citing another director, the much talked about Laura Wandel, whose 2021 film Un Monde (known as Playground in English) scooped seven Belgian Magritte awards.

Dardenne brothers

Luc gave Laura feedback on the script for her latest film, L'intérêt d'Adam (Adam’s Sake), which was screened in the Semaine de la Critique (Critics’ Week) at Cannes. Inspired by a story a paediatrician told her during her research at Saint-Pierre Hospital in Brussels, it is about a nurse trying to keep a single mother from losing custody of her child.

If the topic sounds familiar, it’s no wonder entertainment trade title Variety has named her as the “heir to the Dardennes”.

But she may have to wait a while yet before taking their crown.

With longevity in their genes and no thoughts of retirement, don’t bet against the brothers returning to Cannes for a twelfth visit with their next film. Based on their usual three-year schedule, that would be in 2028.

Could they do something completely different next time?

Perhaps a comedy called Crazy Mères set in Seraing?

“We're tempted,” laughs Luc. “For now, we’re resisting that temptation, but we’d seriously like to make a comedy one day.

“We felt a little lighter making Jeunes Mères and thanks to the babies, we’ve left room for a lot more surprises to come.”

You heard it here first.