In a sun-dappled kitchen in Provence, a vibrant orange cooking pot bubbles gently on the stove, exuding the comforting aroma of a boeuf bourguignon. It is a familiar scene in countless homes around the world – a testament to the enduring legacy of Le Creuset, the iconic cookware brand that, this year, quietly turns 100.

While its cocotte is almost universally embraced as the epitome of French culinary flair, few realise that Le Creuset's roots trace back to Belgium – a humble origin story that, like a family recipe, has long simmered just beneath the surface. And, as we’ll see, it has a very Belgian coda wrapped in a spectacular Art Nouveau design.

Its story begins with the 1924 meeting of two Belgian businessmen: Armand Desaegher, a specialist in casting from Oudenaarde, and Octave Aubecq, an industrialist from Gosselies.

Desaegher brought his foundry expertise, while Aubecq brought knowledge of enamel glazing, as the head of the Émailleries et Tôleries Réunies company.

Their encounter at the Brussels Trade Fair that year is not as storied as, say, when Charles Rolls and Sir Henry Royce met at the Midland Hotel in Manchester, but it led to a much more egalitarian industrial icon.

Together, they combined their know-how to revolutionise cookware by casting iron pots and coating them in colourful enamel — a novel idea at the time.

Desaegher and Aubecq’s venture would, however, be founded across the border, in Fresnoy le Grand a small town in northern France: Picardy was seen as the crossroads of transportation routes for iron, coke and sand.

They set up shop in 1925 in a disused foundry near the railway line – ideal for transporting the raw materials and finished goods.

Octave Aubecq, an industrialist from Gosselies, and behind Le Creuset

They were far from the first to make pots in cast iron – it had been used since Roman times and prized for spreading the heat so food is cooked evenly. But traditional cast iron is high maintenance: its inner surface needs regular seasoning so that food doesn't stick.

Their innovation was the vitreous enamel coating that gave it a smooth cooking surface which was easy to clean and maintain. Desaegher’s precision in casting iron gave Le Creuset its technical backbone, while Aubecq’s enamelling mastery ensured every piece gleamed with a jewelled finish. The resulting cocotte was more than cookware – it was a promise of durability, beauty and gastronomic excellence.

The enamel also offered opportunities for pigmentation. Their first cocotte was coloured after the intense orange glow of molten cast iron inside a cauldron – a creuset in French means crucible or melting pot. Hence Le Creuset's signature fiery colour, Volcanique – or Flame, for English-speaking markets.

Heirlooms and Instagram

It was launched at an auspicious moment. After the First World War, Europe was rebuilding, and kitchens were largely utilitarian. But Le Creuset’s cocotte was not just a pot. It was a symbol of culinary possibility.

Over the decades, Le Creuset became synonymous with timeless design and French savoir-faire. Its colourful palette – now boasting over a hundred hues globally – elevated it to cult status.

Celebrity chefs adored it. Julia Child cooked with Le Creuset on her trailblazing American TV show in the 1960s, effectively launching the brand into the hearts and homes of millions. Marilyn Monroe owned a 12-piece set in Elysée yellow, while Queen Elizabeth was said to be a fan.

Today, Le Creuset is still manufactured in Fresnoy-le-Grand, where molten iron is poured into individual sand moulds, then hand-finished and inspected at least 15 times before leaving the factory. This meticulous process – a century old and still going strong – underscores a rare commitment to craftsmanship in an era of mass production.

Yet Le Creuset’s staying power is about more than nostalgia. It has evolved with the times, expanding its offerings to include stainless steel, non-stick pans and silicone tools. It has 60 colours in its range: this year’s palette includes berry and teal. The cocotte, still the flagship piece, remains relevant not only in professional kitchens but also on the Instagram feeds of a new generation of home cooks.

Le Creuset pots

In Belgium, generations of cooks have reached for their trusted cocottes to coax depth and flavour for dishes like carbonade flamande and waterzooi. Le Creuset pieces handed down from one generation to the next can sometimes outlast the stoves they were first cooked on.

“Our best ambassadors are our customers, who might remember it from, say, their grandmas,” says Marie Gigot Managing Director Le Creuset France and Benelux. “They have family histories, family memories, with our products, and they share that a lot. There's the emotional link that you have: if you're offering that to your granddaughter, it is something she will probably keep for a lifetime. We are something you can trust, something that will last for a lifetime. We are a lifestyle brand. We have a lot more to tell than only cast iron.”

Lost Art Nouveau masterpiece

As for Aubecq, he briefly left his mark on Brussels. He was 60 when he first met Desaegher and had already made a fortune decades earlier with his enamel company. He was rich enough by the turn of the century to commission a house in Brussels, custom-built by the most celebrated architect of the era, Art Nouveau pioneer Victor Horta.

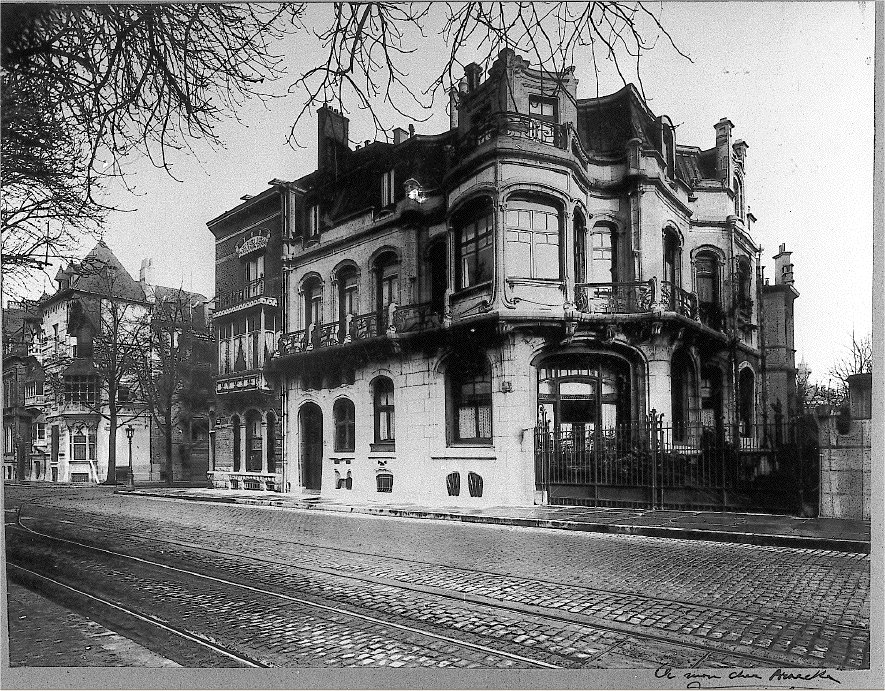

The result was the spectacular Hôtel Aubecq, built between 1899 and 1902, at 520 Ave Louise, next to the Bois de la Cambre. The mansion was notable for its three-sided façades and octagonal rooms, with several arches and balconies made of imaginative ironwork and stones from Modave — an example of Horta’s Gesamtkunstwerk approach, where architecture, interior design, and furniture are seamlessly integrated.

Maison Aubecq

Aubecq died in 1943, aged 79. Alas, the Hôtel Aubecq was one of Horta's masterpieces felled in the post-war modernisation blitz, torn down in 1950 and replaced by an apartment building (a similar fate befell his Maison du Peuple).

Much of the main façade was dismantled and preserved by the then Ministry of Public Works. Some interior elements like stained glass, woodwork, and furniture now reside in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. One can be found at the entrance to Tenbosch Park. Other pieces, numbered, were put on display in 2011. Now they sit in a warehouse in Schaerbeek.

Today, Le Creuset’s boutique in Brussels is at 67A Ave Louise, at the other end of the same grand street from where Hôtel Aubecq was. As it celebrates its centenary – one of colour, craft and cast iron – it is also worth remembering the house that couldn’t last as long as the cocotte.