"It's part of my youth. I learned how to read through comic books," she said.

Like many Belgians, Tine Anthoni grew up reading comics; from big global successes, like Tintin, to Flemish classics like Suske en Wiske. Today, she is the head of communications at the Comic Art Museum in Brussels, where she has worked for around 19 years.

“I’m used to doing interviews. With the Smurfs movie, it’s been non-stop,” she said, referring to the recently released cinematic adaptation of the famous comics created by the Belgian Pierre Culliford.

As we walked through the museum, in search of a spot to talk, Anthoni pointed to a quiet corner, right in front of several life-size statues of the protagonists from Tintin. “Maybe there,” she said.

The Smurfs and Tintin are just two examples of Belgian comics that have found global success, even to this day. But what has made Belgium the home to so many successful comics? While Anthoni admits it is difficult to pinpoint exactly why Belgian comics became so popular she does have some theories.

‘Room for experimentation’

“The long-standing visual tradition is one explanation,” she suggests. With examples like the 14th-century Flemish painters Bruegel or Rubens, Anthoni believes Belgium has had its fair share of skilled visual artists.

In addition to their talent, the artworks often had qualities frequently present in comics. “If we look at some of the paintings of the painters from the Low Countries, there is also a lot of humour in them. Several layers of interpretation [...] it's very symbolic as well,” she adds.

Inside the Comics Art Museum. Credit: The Brussels Times

The artistic freedom in Belgium's comics scene could also be a factor.“We're on the edge of two language areas, but the literary centres of both cultures were in Amsterdam and Paris,” she said. “Most of the book printing and the literary culture was elsewhere, so there was a bit of room for experimentation.”

To add to that freedom, Belgian culture as well as editors and publishers seemed to embrace the medium with ease.“It wasn't looked upon as a minor genre or a genre that would cast a shadow on literature,” she said. ”It was used, for example, in the Catholic press, it was used in the socialist press. Everybody needed to have their comics.”

This acceptance, according to Anthoni, came in part due to the fact that Belgium had several artists who created content that was seen as positive for the youth. The other reason for it was the proof of the global appeal of Belgian comics. This, in part, involved a bit of luck: “The fact that Hergé was Belgian,” Anthoni said.

The Hergé effect

While far from the only successful Belgian comic artist, Georges Prosper Remi, better known as Hergé, was one of Belgium’s “first icons” in the field, as Anthoni puts it.

Hergé is best remembered as the creator of the adventures of the young journalist Tintin, even almost 100 years after the first book was published.

At the Comic Art Museum, there are traces of Tintin everywhere: from the rocket and bust at the entrance, to the Tintin characters which stood behind Anthoni as we spoke. But what made Hergé’s creation stand the test of time?

Tintin objects at the Comics Art Museum. Credit: The Brussels Times

There are few people better equipped to answer this question than Dominique Maricq, who, since joining Studios Hergé as an archivist in 1997, has gone on to write books about the life and work of Hergé.

For Maricq, the “particular” Belgian humour and the modesty commonly felt in smaller countries like Belgium created a solid foundation for comic artists to develop in the country. “Belgium in general does not take itself too seriously,” he said.

While in larger countries like France, the first comic books often were more text-heavy and featured “a kind of literary explanation” of the images, Belgian comics were simpler and more direct, according to Maricq.

Dominique Maricq.

The accessibility that comes with that simplicity, along with the strong visual art style, is in part what allowed Hergé’s works to thrive. “When you read them, even if you don't necessarily know the language, the images speak for themselves,” he said. “There are very simple drawings, which at the same time are quite sophisticated, and that everyone can understand.”

In addition, Maricq thinks Tintin’s success can be attributed to the valued “family” dynamic of the protagonists, as well as the variety of topics featured in his adventures, ranging from, for example, drug trafficking to an oil crisis.

'I'm still reading'

While comic strips are cultural staples of Belgium, the sector isn’t exactly what it was during its “golden age” in the 20th century. “Like all print press, it has become more difficult,” Anthoni said. The loss of comics magazines, like the Tintin magazine, has made it more difficult for newer artists to enter the industry and test their work.

Nonetheless, artists have found workarounds. “We have social media, which for many artists is important to build an audience,” Anthoni said, adding that the growing number of comics’ festivals and competitions also helps to promote creators.

For Anthoni there is also clear support from the language communities in Belgium. This is particularly important when it comes to the creation of grants. “It really helps support and bring new creators, it definitely works,” she said. “We have great artists who have been launched thanks to these grants; Brecht Evens is a famous example,” she added.

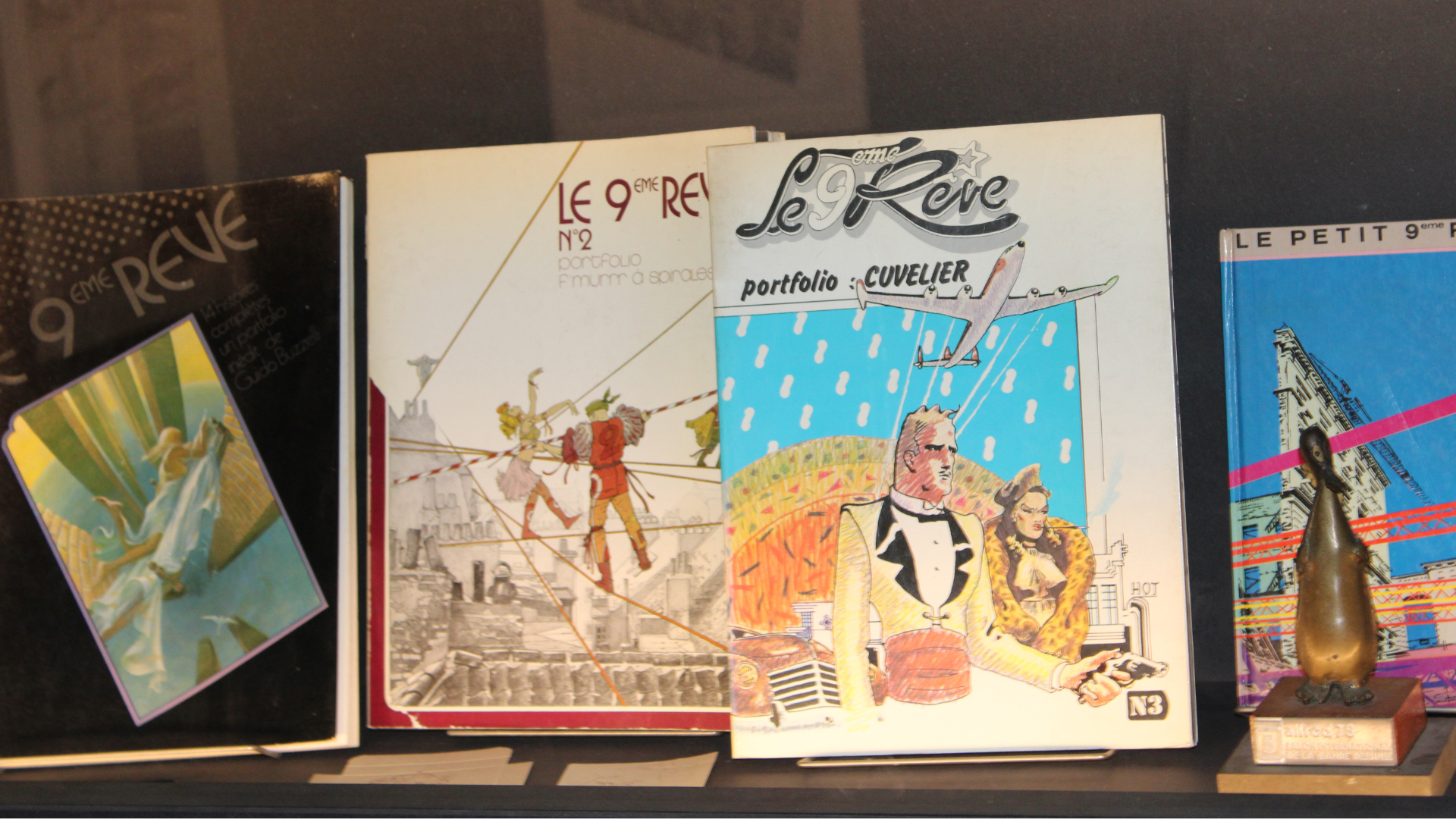

Comic books at the Comics Art Museum. Credit: The Brussels Times

Regardless of the changes in the sector, Anthoni stresses that there is a future for comics, and that interest in the genre is alive not only in Belgium but also internationally. “There’s a lot of manga going on, there’s a big comics subculture as well, and conventions here in Brussels,” she said.

Additionally, there is a rising interest in online comics, particularly with Korean webtoons. Anthoni expects these to properly take off in Europe "in the next couple of years."

Although Maricq understands the appeal of digital stories, for him personally, it cannot compare to the physical versions of comics. “It remains the most beautiful, the noblest material, with beautiful colours.”

Nonetheless, amid changing trends, Maricq underscored the importance of “not losing sight” of comics, whether for younger or older generations. “They’re an incredible way to discover the world, to learn things about life [...] it makes you dream,” he said. “It also shows how many people are incredible artists. Comic book artists are magicians.”

Tine Anthoni. Credit: The Brussels Times

Anthoni echoed similar messages and passion as she walked me through shelves of comic books at the Museum’s library.

While her reading preferences now involve graphic novels with more complex themes, the classic comics that first captured her interest as a young girl are still a part of her daily life. "I saved old comic books, and I'm still reading them to my children.”