Earlier this year, Dutch firm Whiffle, specialists in atmospheric modelling, accused Belgium of a novel offence: wind theft.

Belgian offshore wind farms, they argued, are disrupting wind patterns and reducing yields for turbines off the Dutch coast. “You’re often stealing some of our wind,” claimed Whiffle’s CEO Remco Verzijlbergh in an interview with Flemish broadcaster VRT. Delft-based Whiffle, which advises the Dutch government, insists its stance is apolitical. But its message stirred a breeze of nationalist indignation.

The phenomenon, known as the "wake effect", is well-documented: turbines alter airflow, reducing wind velocity downstream. And with Belgium’s newest wind farms placed southwest of the Netherlands’ offshore clusters, a clash of turbine trajectories was perhaps inevitable.

Belgium currently has 2.3 gigawatts of power capacity from offshore wind—out of 5.6GW in total wind capacity. Another 3.5GW is planned through the Princess Elisabeth Island project, a vast artificial energy island rising 45km off the coast. Construction began in April, with engineers submerging concrete blocks to form its perimeter.

But dreams of a sleek North Sea energy hub are already snagging on reality. The project's modular offshore grid, MOG2, was originally costed at €2.2 billion. Latest estimates put it between €7 and €8 billion. Energy regulators have issued warnings; politicians are muttering about fiscal recklessness.

Underlying these challenges is Belgium’s unique political structure — federated, fragmented, and frequently fractious. Unlike in the Netherlands or France, there is no single minister or national body coordinating wind energy strategy. Offshore wind remains the federal government’s remit; onshore is the domain of the regions. The result is a patchwork of overlapping policies, inconsistent incentives, and sluggish execution.

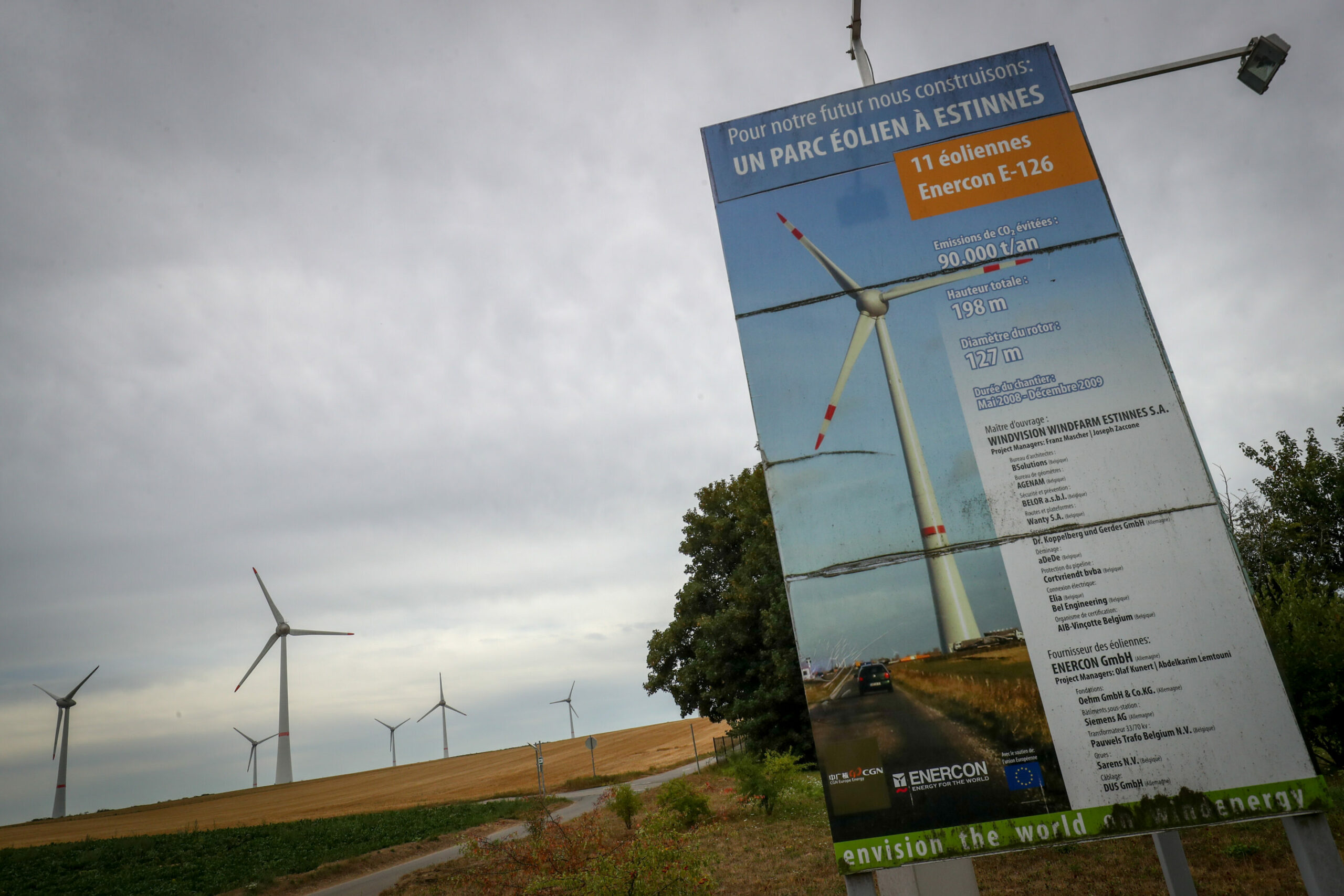

Illustration picture shows wind mills (aolien) at a wind farm in Estinnes, Wednesday 19 August 2020. Credit: Belga

“Of course, it’s a pity we don’t have a national strategy,” says Fawaz Al Bitar, director general of Edora, Belgium’s Walloon and Brussels French-speaking federation for renewable energy. “We need more coordination. But you know how it works in Belgium.”

Despite this, each region has made its own pledges. Flanders, currently with 1,858MW of onshore capacity, aims to reach 2,640MW by 2030. Wallonia, with 1,528MW today, wants to hit 2,500MW. Offshore wind capacity is expected to jump to 5,800MW nationally by the end of the decade.

But the Brussels capital region remains off-limits to large turbines. “You are in the vicinity of the airport with a radar, and so it’s not possible to install a large wind turbine in Brussels — for the moment,” Al Bitar says.

Permits and paradoxes

Wallonia is showing signs of ambition. Its 2030 target is expressed not in capacity but production — 6,200GWh of onshore wind power to be produced annually. That could incentivise the deployment of more efficient, high-output turbines. But turning ambition into infrastructure is no small feat. As of January, Wallonia had 589 turbines across 152 projects, totalling 1,528MW of installed capacity. Reaching the 2030 wind production target would require doubling capacity within five years – and only a quarter of project permits are currently approved. “It’s a major challenge. The commitment is a first positive step. Now the Walloon government has to do everything to make it possible,” Al Bitar says.

The region faces hurdles, particularly in permitting, with only 25% of wind project permits approved. “It is really a pity,” Al Bitar says. He blames both local opposition and government inertia. “We still have a sort of nimby approach to wind projects.”

Flanders faces similar obstacles—though of a more contradictory nature. The regional government has revised its onshore wind capacity target upwards to 2.8GW by 2030, from its previous goal of 2.6GW.

With approximately 1.8GW installed today, the region must commission 200MW annually for the next five years. “Targets can always be more ambitious,” said Maarten Dedeyne, director of the Flemish wind energy association VWEA. “But the real difficulty is how we will realize them.”

In 2024, Flanders installed just 12 new wind turbines — the lowest number in a decade. To hit its goal, it needs 35 large turbines per year, according to the region's Energy and Climate Plan.

Recent developments, though, raise concerns about contradictory signals. Energy Minister Melissa Depraetere, from the centre-left Vooruit, recently reinstated support for new projects, while insisting on there being no repeat of the previous overcompensation for renewable producers. Consumers’ energy bills will remain unaffected.

Yet just days later, Environment Minister Jo Brouns, from the centre-right CD&V, proposed stricter distancing rules. Under the proposed rules, turbines would need to be placed at least three times their tip height from residential areas. Taller turbines can generate up to three times more energy than first-generation windmills, but stricter planning rules for turbines over 200 meters would threaten Flanders’ ability to meet its wind energy targets. The rule would also increase the cost of green energy certificates for wind.

Flemish Energy and Climate Minister Melissa Depraetere. Credit: Belga / Nicolas Maeterlinck

Flanders still needs to decide on the rules, but the tallest 250-meter-high turbines would have to be at least 750 meters away from the nearest home. The rules could severely limit viable sites in densely populated Flanders. “It’s a contradiction,” says Maarten Dedeyne of the Flemish Wind Energy Association (VWEA). “A minister announces good news one day. Three days later there’s bad news for the sector. Regulation cannot change every one or two years. That’s very difficult for projects that need several years from scratch to build.”

Depraetere has since tried to reconcile with her government colleague. “Minister Brouns also agrees with the ambition to install more wind turbines. He might have been somewhat shocked himself by the concrete impact of the ‘three times tip height’ rule, which essentially means you’d hardly be able to place any wind turbines anywhere,” Depraetere told the Flemish Parliament. “No decision has been made about that either. It would also mean that Flanders would practically become a red zone for those wind turbines.”

Depraetere underscored the point that large wind turbines require less financial support and generate more energy than smaller models. The Flemish Energy and Climate Agency (VEKA) has calculated that smaller turbines still need about €20.8 per megawatt-hour in support, though savings on energy costs would outweigh these subsidies.

Nuclear or wind?

Meanwhile, nuclear power is creeping back into the mix. In May, Belgium repealed parts of its nuclear phase-out law, reopening the door for new nuclear development.

“It is no longer a matter of pitting energy sources against each other in a binary, sterile debate, but of using them pragmatically and in complementarity,” Federal Energy Minister Mathieu Bihet, from the right-wing MR, told us. “You need electricity to phase out fossil fuels. You need it for heat pumps, for electric vehicles, for industry. And we don’t have enough of it.”

But renewable advocates like Edora's Al Bitar warn the shift could crowd out wind and solar. “With lots of nuclear remaining on the grid, you’ll have to increase storage capacity or demand-side management capacity. But will there be curtailment of wind and PV?” Al Bitar says.

Minister of Energy Mathieu Bihet pictured during a meeting of the Chamber Commission Energy, Environment and Climate at the federal parliament in Brussels, Tuesday 18 March 2025. Credit: Belga / Hatim Kaghat

On costs compared to nuclear, Al Bitar argues that new renewables still come out ahead. “We have to compare new wind capacity with new nuclear. And here renewables are the cheapest,” he says. Al Bitar also noted that Belgians have already paid for the country’s existing nuclear plants. “If you prolong their lifetime, then existing nuclear plants are not comparable to new wind farms,” he says.

Indeed, offshore wind farms now reach capacity factors of 50%, with onshore installations averaging between 30% and 45%. That outpaces solar PV at 20%—though still lags nuclear’s formidable 90%.

Silver linings, stiff headwinds

Belgium is hardly a failure when it comes to renewables. “No country in the world today has more offshore wind per square kilometre of its sea space than Belgium,” says WindEurope CEO Giles Dickson. Public support is also strong, with over 70% of Belgians backing onshore wind.

One reason is that onshore wind farms pay money via taxes to local town halls. Belgium’s model tenders to finance wind projects minimise financing costs, with developers offering the lowest price winning bids. The country uses a contracts-for-difference (CFD) model for wind auctions, offering guaranteed revenue for at least 15 years, potentially lowering financing costs. “There’s also a non-price criterion — the level of community participation in the project,” Dickson tells us.

Challenges remain even as Belgium actively expands its wind energy sector with the Princess Elisabeth offshore wind island. Plans for a second UK-Belgium interconnector to Princess Elisabeth are “on hold” due to rising HVDC power cable costs. Wind provided 18% of Belgium’s generation mix in 2024, slightly below the European average of 20% but ahead of Belgian solar at 12%. “Wind is by far Belgium’s most important renewable source of electricity,” Dickson says.

Illustration picture shows a wind mill at the Antwerp Cold Stores in the port of Antwerp, Wednesday 10 May 2017. Credit: Belga

Still, persistent permitting delays weigh heavily. New EU rules stipulate that all renewable projects must be treated as matters of overriding public interest, with permits issued within two years. Yet Belgium has been slow to implement the new framework, and risks infringement proceedings if it fails to submit its revised national energy and climate plan to Brussels.

While Germany is actively applying these rules, Belgium — like many other EU countries — lags behind. Ultimately, it’s up to the Flemish and Walloon governments to implement the new EU permitting rules for onshore wind in Belgium. So far, Brussels has yet to install wind turbines.

Additionally, Belgium, alongside Poland and Estonia, faces potential proceedings at the European Court of Justice if it doesn’t submit long-delayed national energy climate plans to the EU. The deadline has already passed. Those plans should detail how wind and other renewables will help cut greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.

Other priorities include fully digitalising permitting processes as required under EU law and further building out grids both offshore and onshore to support heavy industry electrification, such as in the Antwerp petrochemical cluster. Belgium could also embrace repowering — replacing older, less efficient turbines with modern ones on existing sites — increasing output while potentially reducing the number of turbines. It’s a win-win, delivering much more energy from the same wind farms.

In Denmark, wind makes up over half of all electricity produced. In Germany, the figure is about 30%, much of it in the densely populated north. So Belgium — with 16% wind in its power mix — cannot use population density as an excuse. There’s still plenty of room for new wind farms onshore.

Belgium’s wind and renewable energy sector faces growing pressure as Europe races to slash greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 and achieve climate neutrality by 2050. The wind may not always blow in Belgium’s favour. But the country has the tools — if it can summon the political will to use them.