In the late 1960s, growing up Moroccan in Molenbeek, I walked between two worlds: the grey melancholy of immigrant Brussels and the vibrant, borderless panels of Tintin’s adventures.

Hergé’s stories offered more than escape. They were maps of possibility, full of humour, daring, and the thrill of movement. In Les Aventures de Tintin, I found the freedom denied to children like me, at a time when belonging always seemed just out of reach.

But decades later, rereading those same stories with adult eyes, I saw something else: grinning caricatures, silent side characters, and easy European triumphs. The comic hadn’t changed. I had.

Some stories stay with us until they don’t. Until the heroes we once loved reveal shadows we missed.

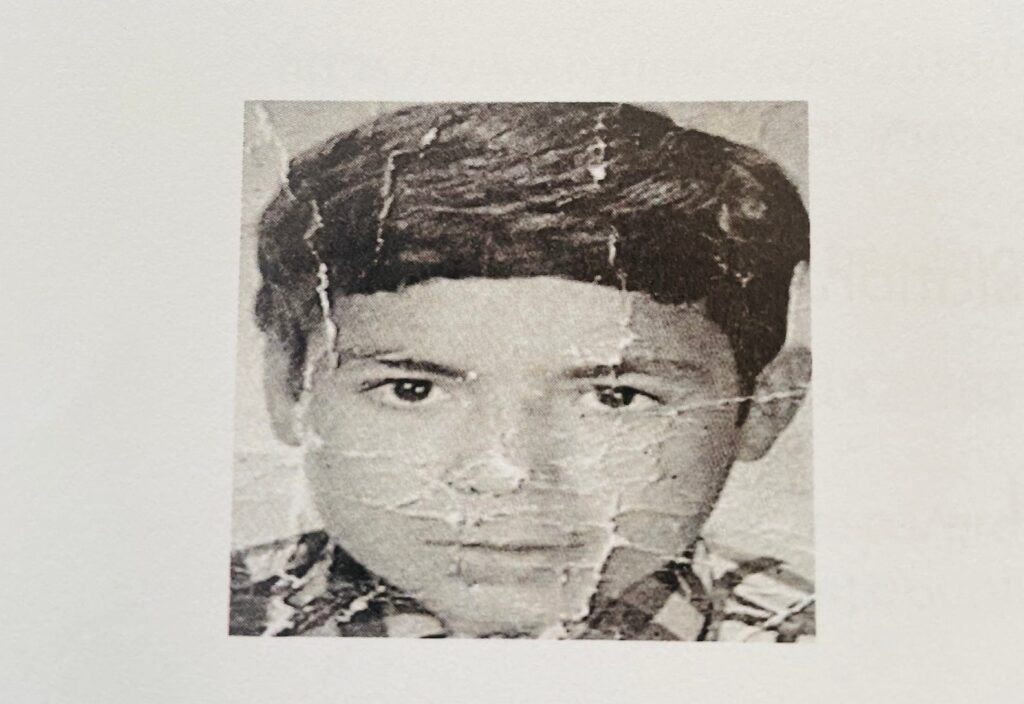

As soon as I learned to read French, I joined the ranks of Belgian children enchanted by Tintin’s world. I will never forget my first encounter with Tintin au Congo. I was eleven. The cover alone — Tintin driving through the savannah with Snowy beside him — swept me into a world of colour and promise. It felt like stepping from Belgian gloom into Africa’s luminous possibility.

As a child, the panels felt boundless. But as I grew older, they began to trouble me. A Congolese boy my age smiled while carrying Tintin’s bags. His features were exaggerated. Tintin tamed animals and commanded admiration. His cleverness, once thrilling, began to feel unsettling — not because I had changed, but because the story had always carried a distortion. I just hadn’t understood it yet.

That shift from awe to discomfort was gradual, shaped by time, education, and awareness. What once felt like pure adventure began to reveal colonial views hidden beneath the surface. Published in 1931, Tintin au Congo mirrored a Belgium still clinging to its empire. The Congo wasn’t portrayed as a place but as a stage for European triumph. It passed as bande dessinée, but it was also colonial fantasy dressed as innocent escapism. For those like me who once saw ourselves in Tintin, the realisation was jarring. The joy it once sparked now demanded a reckoning.

Later, I travelled in spirit with Tintin to America. It was my first encounter with cowboys and so-called “Indians.” I raced through Tintin en Amérique, swept up in feathers and gunpowder. But rereading it years later, it felt theatrical and hollow. The “Indians” appeared stoic and silent, moving without voice or depth. I began to ask: who gets to speak, and who remains in the background?

These were no longer childish questions. They marked the beginning of a deeper literacy — not just of language, but of representation and power.

I couldn’t afford the albums, so I borrowed them from a modest public library on Rue Reimond Stijns. That quiet space became a sanctuary. There, I met a woman who came to mean more than she likely ever knew. The librarian — her name lost to time — helped immigrant children like me stumble toward language.

She reminded me of Madame Jeanine, the café keeper across from our flat. Two Belgian angels. Quiet stewards of kindness.

She wore no name tag, and in those days, it was considered impolite to ask an adult’s name. I remember not what she was called, but how she made me feel. She was a guardian, not just of books, but of children learning to belong.

One afternoon, I asked her innocently, “Madame, do you live here?”

She laughed, her voice rising like warm light among the shelves. “Sometimes it feels that way,” she said. “But no, I have a family too.”

From then on, she greeted me with a smile.

“Ah, the little Moroccan who loves Tintin. Haven’t you read them all by now?”

“No, Madame,” I would reply — though I had.

She knew. I knew. We smiled.

Her kindness came with rules. Whenever she heard chatter, she’d call out, “No talking. Quiet. This is a library. Only serious people here.” Teasing, but warm. Even silence felt gentle.

In that small library, surrounded by the scent of books and the hush of a Molenbeek afternoon, I felt a real sense of belonging. My papers said immigrant. But there, I was Belgian. And curiously, it felt very Moroccan too. I dreamed in two languages. I walked between two worlds. I loved them both.

I remember the low skies of Brussels, the quiet dignity of working-class Molenbeek, the weekly horse market, and the annual circus at Place de la Duchesse. And I also remember a curious feeling: la Belgitude. Not quite French. Not quite Dutch. Somewhere in the middle, tinged with melancholy and absurdity.

La Belgitude is a contradiction, fragile but resilient. For immigrants like me, it made space in the in-between. To claim it wasn’t to become Belgian in the eyes of the state, but to feel Belgian in spirit. Everyone carries it differently. It’s not something you understand. It’s something you feel.

Resistance to la Belgitude is futile.

Years later, at university in Massachusetts, I revisited Tintin through the lens of postcolonial literature and sociology. I was no longer the boy from Molenbeek, but a young man learning to question stories.

Professors like David Landy and Donaldo Macedo — himself once an immigrant from Cape Verde — helped sharpen my awareness. I read thinkers like Edward Said and Abdelkebir Khatibi. They gave me tools to understand how literature can disguise domination as adventure, how even innocent tales carry power.

What was once invisible became glaring. Caricatures, silenced histories, skewed portrayals. Tintin’s Africa was not mine. It was fantasy, drawn by someone who never had to live its consequences.

I remember a snowy afternoon in 1969. The little library glowed. I held Les Bijoux de la Castafiore in my hands. Tintin was beside me. Snowy just ahead. Captain Haddock muttering. The bumbling twin detectives. Castafiore shattering glass.

These weren’t just characters. They were companions. They taught me humour, curiosity, and courage.

By childhood’s end, I had read every Tintin volume several times. I felt I had crossed continents without a passport. But those journeys weren’t neutral. They were shaped by Hergé, a man of his time, carrying colonial assumptions.

In recent years, publishers have started acknowledging Tintin’s legacy. Tintin au Congo now comes with context. Some editions add editorial notes. Even Hergé expressed regret: “I was fed on the prejudices of the bourgeois society in which I moved.” His later work, especially Tintin in Tibet, reflects more introspection. Less conquest. More connection. It was his favourite.

That, too, is part of the story.

The irony still gnaws. I admired Tintin, but I was closer to the silent figures in the background, the ones who carried his bags and helped his triumphs seem effortless.

Yet I can’t reject Tintin outright. To do so would be to erase my joy, and my childhood. The warmth of that little library. The gentle authority of a librarian who made space for children like me.

Today, I live far from Molenbeek, on Wampanoag land in New England. My wife and I babysit our grandsons every Tuesday. We visit parks and libraries, and laugh together.

When it’s time to unwind, I ask, “Boys, what do you want to watch?”

Without missing a beat: “The one with the yeti!”

It’s Tintin in Tibet, their favourite. I think old Hergé would have liked that.

There’s one scene they never tire of. Snowy, Tintin’s loyal little dog, gets hilariously tipsy.

“What is Snowy drinking, Papi?” they giggle.

“It’s the Captain’s medicine,” I say.

We all dissolve into laughter, our inside joke funnier with every telling.

It’s a new kind of journey. I once travelled through panels and pages. Now I travel through their delight.

I still give them Tintin. But I also give them perspective. We laugh. We reflect. We learn. The stories are no longer just escapes. They’re openings — to understanding, to growth, to grace.

And sometimes, I imagine the librarian again, calm and composed, her kindness echoing across decades.

She gave me belonging.

Now I pass that forward.