Sleepy Belgium does not often figure in the annals of political murder. But when it does, as with many things in the country, the stories are rarely simple.

During the Cold War, Brussels, as the de-facto European capital, became a microcosm of shadowy networks, organised crime, political intrigue, espionage and racketeering. Through the last half a century, several high profile killings have rocked the country, reminding that while small, Belgium remains a place where intrigue is woven, and abruptly ended.

From a communist gunned down for his republican views, to a veterinarian shot for challenging the mafia, numerous high-profile assassinations have taken place in Belgian soil, some even taking place on the streets of Brussels.

Julien Lahaut (1950): A gunman at the door

On the night of 18 August 1950, two men rang the bell at 192 Rue de la Vecquée in Seraing.

When the door opened, they asked to see the occupant: Julien Lahaut, a veteran of the resistance, a federal politician and chairman of the Communist Party of Belgium.

Moments later, gunfire. Lahaut fell in the doorway and was declared dead within half an hour. Lit by street lamps, the killers sprinted to a waiting car and fired again towards the house before vanishing into the late-summer dark.

Four bullets had struck Lahaut; an autopsy found the fatal shot to his abdomen. Days later, an estimated 150,000 mourners paid their respects to the slain politician past his coffin. This case still represents one of Belgium’s most brazen political assassinations in its history. But what was its motive?

Flowers are left in front of the Julien Lahaut memorial by supporters in the cemetery of Seraing. Credit: Belga/ Olivier Matthys

Just a week earlier, the Belgian Parliament had sworn in 20-year-old Prince Baudouin as its new regent after the long standoff over King Leopold III, a monarch accused of collaboration during the Germany occupation of Belgium in 1940-1945.

During the ceremony, Communist deputies were heard to cry “Vive la République!”. It is unclear exactly who shouted the anti-monarchist sentiment, but some accounts placed the words in Lahaut’s mouth.

Against the backdrop of the riotous climate of the “Royal Question,” it hardly mattered. The murder was quickly read as a royalist hit against the political left. The poor handling of the investigation and a series of mismanagement only fuelled suspicion that the assassins had connections with powerful individuals within the state.

The crime scene was crowded by onlookers, evidence was routinely mishandled, and valuable leads from the police were ultimately sidelined. For decades the case was left unresolved.

Only much later, in 2015, would historical research commissioned by the Belgian Senate pin the case on an anti-communist network based around former intelligence agent André Moyen, and his accomplices.

To the day, accusations remain that the judicial process was deliberately compromised or sabotaged. To date, no perpetrator has ever faced court.

Karel Van Noppen (1995): The ‘hormone mafia’

At dusk on 20 February 1995, veterinarian-inspector Karel Van Noppen left his home in Wechelderzande, near Lille in Antwerp Province. Even from his unassuming position, van Noppen had made enemies, and they would soon seek their revenge.

As a public servant he pursued the illegal use of growth hormones in Belgium’s cattle industry, a lucrative, violent, and well-organised trade.

That night, on a nearby road, his car was forced to stop. A window shattered. Three shots. Van Noppen died at the wheel. While the story shook the sleepy Flemish municipality; it would take years for the justice system to piece the mystery together.

File picture dated 21 February 1995 of journalists and policemen seen near the house of Karel Van Noppen, a 42 years old veterinary working for the public health service, who was killed on 20 February 1995. The assize trial against Albert Barrez, Carl De Schutter, Germain Daenen and Alex Vercauteren, accused of the murder on Van Noppen, started Monday 15 April 2002 at the assize court of Antwerp. Credit: Belga/ Jacques Collet

The ensuing investigation, riddled with false starts and retractions, nonetheless delivered what many families of political murder victims never receive: convictions.

In 2002, a court handed down a life sentence to Alex Vercauteren, identified as the mastermind of the hit, and gave long sentences to Carl De Schutter, Germain Daenen and Albert Barrez for roles as organiser, intermediary and gunman.

The case helped bring about tighter regulation in the agriculture sector and better protections for civil servants. The case even reached the big screen. In 2011, Michaël R. Roskam released Bullhead, a bleak portrait of the animal hormone underworld, which drew heavily from Van Noppen’s assassination.

“We should be grateful to him,” a local mayor said at a 30-year commemoration this February, “for the ‘purer piece of meat’ on our plates.”

Gerald Bull (1990): Supercannon and a Mossad hit

On 22 March 1990, a 62-year-old Canadian engineer returned to his flat in Uccle, Brussels.

Gerald Vincent Bull had spent a lifetime chasing an audacious idea: to fling payloads into the upper atmosphere using giant artillery pieces. In the late 1980s, at the height of unrest and upheaval in the Middle East, he put that expertise to the service of Saddam Hussein’s authoritarian Iraq.

Project Babylon, the “supergun”, threatened to give Iraq the capacity to launch satellites into space or serve as a novel type of weapon. Israel, following a series of wars backed by Iraq and its neighbours, kept a close eye on the development of the project.

Gerald Bull, at far left, photographed at the Space Research Institute, McGill University, Canada in 1964. Bull was a instrumental part of an Iraqi programme to build advanced orbital cannons. (Credit: WordClerk/CC BY-SA 3.0)

In Uccle on that mild evening, as Bull reached his door, an assassin opened fired at the scientist five times at point-blank range. The job was professional. Shots hit Bull in his neck, head, and back.

When Brussels police arrived, the key was still in the lock. His briefcase, said to contain around $20,000, lay untouched. There were no signs of robbery, only a calculated execution. No arrest ever followed.

Who ordered the hit? The consensus among the intelligence community points towards Israel’s Mossad. The killing was likely one of Israel’s many extrajudicial killings; a pre-emptive strike on Iraq’s long-range capacities. Israeli officials have never confirmed this.

Nevertheless, a former senior Mossad figure told PBS in 1991 that Bull’s killing was “a state execution of an enemy of the state”, without naming the state. Other theories implicate multiple intelligence services, from Iran to Britain.

The message sent by the killing was clear. A foreign state attempted to ensure that Saddam’s “doomsday gun” would not fire. Ultimately, the project was scrapped, although sections of test models can be found at the Royal Armouries in Portsmouth, in the UK.

Naïm Khader (1981): Slain diplomat

09:00, 1 June 1981, Rue des Scarabées, Ixelles. Naïm Khader, the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) representative to Belgium and the European institutions, stepped out of his building to go to the office. A man awaited him.

The quiet street was awoken to gunshots, around five or six by contemporary accounts. One bullet struck his heart. Khader, a Catholic Palestinian and an advocate of a secular two-state peace, died on the pavement, while the killer escaped on foot.

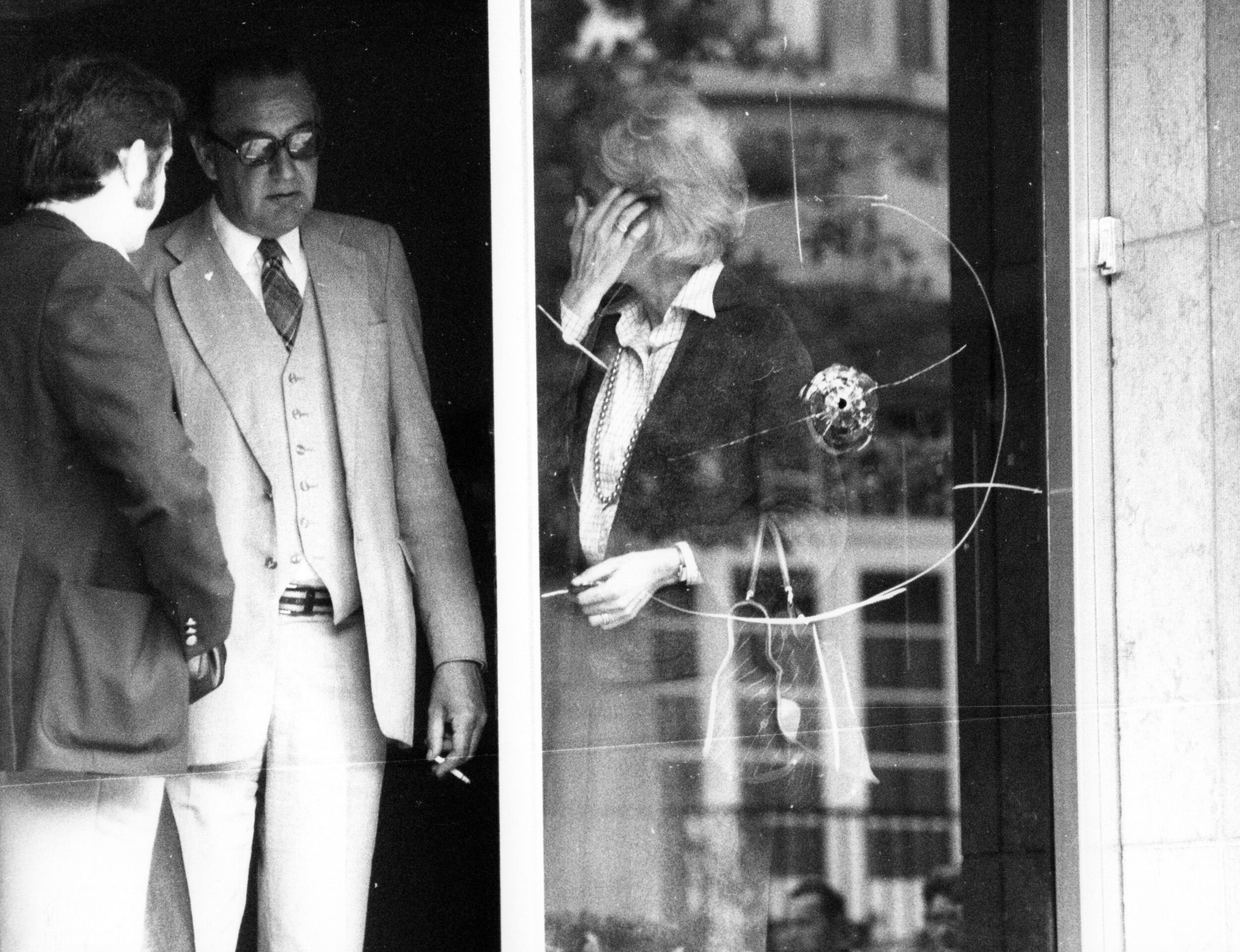

File picture dated 1 June 1981 shows the crime scene of the murder of Naim Khader, Europe's main representative of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Europe. He was killed in front of his house at Ixelles (Brussels). Credit: Belga Archives

Within hours, accusations flew. The PLO blamed Israeli agents; Israel denied involvement. The file would migrate across decades, a suspect would be tried and acquitted years later, and the case would remain unsolved.

The PLO accused Israeli intelligence of carrying out the assassination, linking it to a pattern of killings of its representatives in Europe. A suspect tried in Vienna was acquitted for lack of evidence. Khader’s funeral was held in Brussels with diplomatic and community representatives in attendance; his body was later flown to Jordan for burial in Amman.

André Cools (1991): Corruption and scandal

It was 07:25 on Thursday, 18 July 1991, when two gunmen opened fire on André Cools and his partner as they left an apartment block in Liège.

Cools, former deputy prime minister, mayor of Flémalle, and a mainstay of the francophone socialists, died at the scene; his partner survived. The crime was a bombshell in Belgian politics.

Quickly, theories spiralled behind the possible motives behind the murder of one of Belgium’s most prominent politicians.

Trails seemed to lead in many directions, with the assassination being wound into larger investigations, notably the Agusta–Dassault affair, a series of scandals surrounding bribes paid to seal valuable defence contracts.

File picture from 18 July 1991 shows the municipal morgue of Liege taking away the coffin with the body of Belgian socialist minister and trade union leader Andre Cools. Andre Cools was murdered on 18 July 1991. The assassination launched a number of investigation into corruption scandals within the Belgian government. Credit: Belga

Years of investigations and false leads followed, including a Tunisian trail through Sicily. In 1998, two Tunisian nationals were convicted in Tunis for carrying out the assassination. In Liège in 2004, a Belgian jury convicted six men with links to PS circles for organising roles in the murder, from its logistics, accommodation, transport, though the deepest question of motive, and whether the killing connected directly to corruption probes, remains contested.

Related News

- Belgium marks 30 years since 'hormone mafia' murdered vet

- Today in History: Frank 'Burn the money' Vandenbroucke resigns after Agusta scandal

- Belgium's biggest corruption scandals

Cools’ assassination was only the second of a sitting or former national-level politician in modern Belgium, after Lahaut.

The legacy of Cools, and his rumoured relationship with a series of high-profile cases surrounding Belgium’s socialist leadership, still resurface today. New prosecutions, extraditions, arrests and in-absentia convictions have kept the case sporadically alive in the news three decades on, with further arrests linked to his assassination and corruption scandals.

For a generation of Belgians, the murder stands as a grim reminder of old-style clientelism that plagued Belgium well into the 1990s and 2000s. The Cools cell of politicians left lasting damage to the reputation of the French socialists and showed how the line between crime and government was so easily blurred.