Their ears can grow the length of your forearm, their bodies stretch nearly a metre from snout to fluffy tail. With big round eyes, long twitching whiskers and the temperament of a particularly affectionate Ragdoll cat, it’s hard to imagine how anyone ever looked at the Vlaamse Reus – or Flemish Giant - and came up with the beer-soaked dish lapin à la Gueuze.

The origins of the Flemish Giant rabbit are somewhat murky, but most people place its beginnings in 16th-century Ghent, where it was prized for its ample meat and warm, soft fur. Farmers bred them for size and hardiness, producing rabbits that could feed working families and also tolerate the damp, Flemish climate.

By the 19th century, the breed had spread across Europe – braised, stewed, roasted or turned into terrines, pâtés and rillettes. But somewhere along the line, as industrial farming reduced the need for backyard livestock, the Vlaamse Reus moved from the menu to maison.

It isn’t difficult to see why. With an average weight of six to nine kilograms and a calm, social personality often compared to that of cats (these giants can be litterbox trained) or dogs (without the barking), Flemish Giant rabbits tick all the boxes for the ideal family pet: cute and cuddly, with a sparkle of personality.

Michelle Van de Poel has been keeping Flemish giants since she was a teenager, and now has space for up to 20 of them at a time in her home. She boards them, breeds them and shares them with the world via her Instagram page, michellesvlaamsereuzen, where she’s racked up over 11,000 followers.

Michelle van de Poel and her Flemish giant rabbit

“Flemish Giant rabbits are really big rabbits, but also have an incredibly gentle character,” she says, attempting to succinctly summarise, in just a few sentences, the magic that makes these unique rabbits so special to so many people.

“I’ve kept other rabbits as house pets, and those are much more timid and less pettable than Flemish rabbits. The Flemish rabbits enjoy affection. And having such an eye-catcher, such a large rabbit in your house – I’ve always found that just so fun.”

A very Belgian rabbit

The breed’s Belgian-ness runs deeper than the name.

“Giant rabbits have been around for a long time, before the term Vlaamse Reus was officially coined somewhere in the 19th century,” Van de Poel explains.

“From there and since then, they’ve been exported all over the world and there are small differences between the ones bred in America, or in the UK, compared to Belgium. And the points on which they’re graded during exhibitions are different.”

Baby Flemish Giant Rabbits

In other words, there are measurable criteria for how Belgian a Flemish Giant rabbit can officially be. International groups abound on social media, where the Flemish Giant rabbit or similar oversized breeds (for example, the Continental Giant) have generated both hype and adoration.

The nuances between the types are well understood by professional fanciers like Van de Poel, who know which colours and traits are official breed standards and which, while hallmarks of the species (dark nose, dark eyes, dark paws) aren’t necessarily part of the official description, even if they’re what garner oohs, aahs and Instagram likes.

“The truly official colours are black, blue, fawn, chinchilla, white, blue-grey, konijngrijs (grey) and ijzergrauw,” Van de Poel says, listing off the colours the way a sommelier recites grapes. The last one, ijzergrauw, is tricky to translate – think a sallow, iron-grey.

With hobby breeding on the rise, new and off-standard shades cropped up online. Older breeders coach younger ones to keep the record straight and the tradition thriving, separating facts from fads.

Seasonality seems to play a role in public interest, which spikes in spring (Easter’s long cultural shadow, undoubtedly) and then fades in high summer and midwinter. Autumn is when most exhibitions take place, and Van de Poel acts accordingly: she breeds her prize rabbits in spring so that they’re heavy enough by autumn to qualify for contests and competitions. That range is about frame and bone – extra kilos aren’t bragworthy, though this misconception persists and is most clearly evidenced by people posting high weights on social media as ‘proof’ of the giantness of their rabbit.

Flemish Giant rabbit and dog (for size)

“A healthy weight is between six and nine kilograms,” Van de Poel emphasises. “Bigger isn’t automatically better; it’s often unhealthier.”

She chooses her stars when they’re between five and ten weeks old. The studs with the best scores are bred, the others find homes as pets.

The family-friendly aspect is not to be undersold: the Flemish giant tolerates (perhaps thanks to its size) the affections and snuggles of infants and toddlers, and will not bite or scratch or nip.

“If a child becomes too rambunctious, or a behaviour too intolerable, the rabbit will simply hop away,” says Van de Poel. She knows this first-hand, having introduced her daughter to their giant, cuddly pets when she was just four months old.

Living with giants

Caring for the rabbits is relatively straightforward (prepare to shop in the dog section of a pet supply store for equipment like carriers), although would-be owners should know that Flemish rabbits can be talented escape artists. Instead of using their enormous hind legs to clear fences, Van de Poel’s rabbits love a good dig. They’ve burrowed their way out of the yard and into the gardens of neighbours, who occasionally ring Van de Poel to let her know that they’ve got a cuddly, if unexpected, convict visiting.

“One of the neighbours called the other morning and said, ‘There’s a rabbit in my driveway, is this one yours?’ When I said yes, he then plopped him in the boot of his car and drove him back over.”

What the Flemish Giant rabbit is not is a high-maintenance plush. In the shift from hoofdgerecht to huisdieren, hardiness won out. The rabbits, particularly when paired with another rabbit companion, are highly independent.

“For young people without children who want a pet, but travel a lot, or have to be out of the house often and don’t have a lot of time for a cat or dog at home, Flemish rabbits are seen as a great pet,” Van de Poel says.

“It’s best to have more than one – they don’t like to be alone – ideally a castrated male and a female. They love to spend time together. They bathe each other, they take turns keeping watch over one another. They do need people, but way, way less than a cat or a dog does. And you don’t have to walk them. Just keep their house clean, and give them food, water and toys.”

Van de Poel’s rabbits live outside, where they bask in the sunshine and nestle in the grass. But many choose to give their rabbits the life of a truly domesticated pet – one that eats and sleeps indoors with the family. This isn’t without its risks, Van de Poel notes.

Man with Flemish Giant Rabbit

“I often hear from people with rabbits in their teenage years that they wage war against furniture, rugs, sofas. The teenage years for a rabbit are a period that can sometimes be a little intense,” she says.

Van de Poel’s teenage years were when she first began keeping rabbits. “I lived with my parents and my aunt got me my first Flemish Giant rabbit as a gift. Then, I got another. And another. Soon, I went from a cage in the garden, to a bigger cage, to a hutch that my father built. At one point, half the yard was dedicated to homes for the rabbits. When I eventually moved out into a house of my own as an adult, my father said: alright, it’s time for the rabbits to move out, too.”

She laughs at the memory, adding, “But my parents have always supported the hobby and taken part in the caregiving. I grew up with it. We’ve always been animal lovers.”

From food to feeds

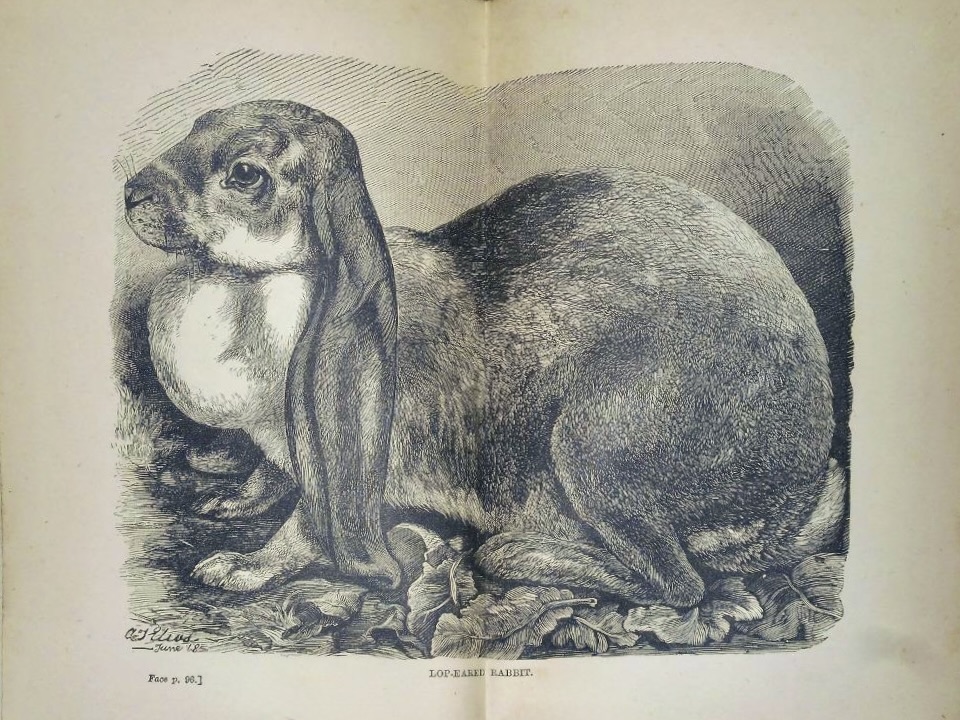

A rare first edition of The Practical Rabbit Keeper from the 1870s depicts Dutch, lop-eared, Himalayan and Angora rabbits printed on foxed pages. Published not too long before Peter Rabbit made his cultural debut in 1902, the black and white pencil sketches capture creatures long beloved – by fanciers, fans, and yes, chefs.

On Van de Poel’s Instagram page, a more colourful and modern catalogue can be found: Hyacinth poses before purple loosestrife in full bloom; Villanelle is a ball of white fluff at just 16 days old (by 14 weeks, she’ll be pushing five kilograms and her ears will already clear 20cm); Muffin and Cosmo blink open their eyes for the first time and nose through yellow hay beside their mother. Pip, whose ears seem improbably bigger than his growing body, delights in a pile of fresh green grass.

A Flemish Giant Rabbit sketched in the 'The Practical Rabbit Keeper' book

Van de Poel has found a new way of sharing, a new way of showing, but it’s the same tradition, the same love, the same blend of expertise braided with affection that began in Flanders and has spread around the world.

What does it mean to carry on this Flemish tradition? Like most Belgians, she’s averse to grandiosity. Humility, like beer, chocolate, bicycles and enormous bunnies, is deeply cultural.

“For me, it’s a little bit like a hobby that’s gotten out of hand,” she says, grinning. “I’ve been keeping rabbits since I was 15, so for almost 15 years now. It’s become a passion. I’m a nurse by profession, and so every hour I can spend with the rabbits is a moment where I can relax.”

In some Brussels brasseries, lapin à la Gueuze lingers on the menu. But after a scroll through photos, reels and stories featuring fuzzy faces and oversized ears, it feels like an anachronism. The Flemish Giant may have started in the larder, but these days, it’s in the living room.

Latest edition of The Brussels Times Magazine is out now!