What fascinates me about electricity pricing policies is how much of a complicated puzzle they are. Headlines tell us solar is booming, rooftops are filling with panels, and Europe is on the right track.

Yet that is only part of the story. It does not tell us whether energy is being consumed efficiently, or who truly benefits and who pays the cost.

Being on the right path does not just mean that people are installing more solar panels; it also means that they are using the energy they produce. If people are producing only to sell to the grid, they create additional problems—especially congestion—and increase the expenses and complexity for the public authorities who manage the system.

Pricing policies shape not only whether people install solar panels but also how much they choose to consume themselves. This is a very technical field, and as a political scientist I often see how complexity shuts people out of the conversation.

That is a problem, because public buy-in matters and public opinion is necessary. At the risk of sounding pedagogical, I believe opinions can only have meaning if we depart from a shared understanding—something that, in my experience, is lacking when it comes to energy.

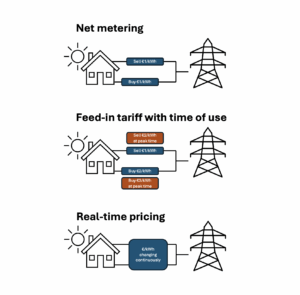

Broadly speaking, there are three types of policy regimes for solar households:

Net metering

This is the least complex system. Every kilowatt-hour exported to the grid is credited at the same value as electricity imported—in other words, what you pay for electricity is exactly what you receive for selling it. The advantage is that it is economically attractive for homeowners and straightforward to manage.

With net metering, there is no incentive to buy a battery since you earn as much by exporting as you would by storing energy for later. Its simplicity and cost makes net metering an effective way to encourage household adoption; but it also encourages oversizing. That is why net metering was the first policy implemented in many European countries and why it helped kick-start the solar boom we often read about—but also why countries are now phasing it out, provoking discontent among early adopters who feel betrayed by shifting rules.

Feed-in tariffs combined with time-of-use pricing

This model, now more common, values exported electricity lower than power bought at peak times—in other words, you pay more for consuming during busy hours than you get for selling. As a result, it makes sense to install a battery and use one’s own energy.

If we think in terms of self-consumption and grid health, this is a much better system. But it is more complex, demanding that panel owners change their habits and actively manage their consumption.

The economics are also tougher, since saving money requires investing in a battery that will eventually wear out. This means that while it is a better system for self-consumption, it is not ideal for encouraging mass adoption of new panels.

Real-time pricing

This is the most efficient model but also the most complex. In this framework, prices change hourly, sometimes even turning negative. From an efficiency perspective, this is the best system, because it is highly sensitive to real weather conditions. But it also demands digital literacy, smart management tools, and a tolerance for volatility.

Governments are increasingly favouring this model with positive results but also some backlash. In Germany this year, households were actually paid to consume electricity when prices went negative for hours. Meanwhile, in Ireland, the Irish Commission for Regulation of Utilities has delayed half-hourly dynamic pricing until mid-2026 after suppliers warned that rolling out an “energy-nerds only” product without mass consumer education would backfire.

The lesson across these regimes is simple: rules determine not just whether households install solar, but whether they consume it themselves and whether they invest in batteries. A solar boom on its own can be misleading. If panels are installed without incentives for storage, the effect is to overload the grid at midday and force reliance on expensive imports at night.

So what is the way forward?

First, avoid net metering systems, where a solar boom does not necessarily signal sustainability but rather stress on the infrastructure we all pay for. But if we want people to continue investing in solar, we must preserve economic attractiveness. We can do this by subsidising batteries.

This is already happening to a large extent. However, the size of the batteries matters as well. Larger storage units significantly increase self-consumption and make systems more efficient. They allow households and communities to match generation with demand with real-time pricing.

Policymakers should therefore design incentives that reward scale—higher subsidy rates for larger systems, and legal frameworks that make it easier for communities to share one large battery rather than each investing in smaller, inefficient ones.

Finally, the conversation must be accessible. Energy policy cannot remain the domain of engineers and specialists. Citizens must be able to understand the trade-offs, contribute their perspectives, and see themselves as participants in the energy transition. For that to happen, the discussion needs to be framed in plain language.

Only then will debates about solar panels, pricing rules, or batteries stop feeling abstract and start becoming part of how communities think about their own futures.