Christmas 1944. The Battle of the Bulge raged on in the snow-filled Ardennes. Léon Praile was among the 33 residents of the nearby Belgian town of Bande being marched towards an empty house after being captured by the Nazis.

Most Belgian towns, including Bande, which dot the German border, had been liberated on 8 September 1944. Since the D-Day landings in Normandy, the Allies had been successfully kicking the Germans back across Europe.

For the Nazis, victory was increasingly slipping away. While in these Belgian border towns, there was a belief that the war was over for them, Berlin had other ideas.

In December 1944, Hitler ordered a new offensive through the Ardennes as a last-gasp attempt to stop the Allied advance across Europe. He wanted to seize the momentum, just like they did in 1940 with the Blitzkrieg through Belgium and France.

American 290th Infantry Regiment infantrymen fighting in snow during the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944.

The Nazi führer wanted his troops to smash through the idyllic Ardennes to retake key territory, particularly the strategic Port of Antwerp. Even if this time round, they lacked manpower and resources, notably fuel.

The initial offensive had not gone to plan, but the Nazis successfully created a 'bulge' in the Allied lines around Bastogne – earning the name of the now infamous battle. Bande, a bit further west, was among the villages retaken on 22 December.

The sub-zero conditions, the snow and the forest terrain made this one of the harshest battles of the Second World War.

Furthermore, residents in Bande and surrounding towns were now faced with the return of the invaders and their collaborators, who were seeking revenge.

Retribution against civilians

On 5 September that year, three German officers had been killed by local Belgian Resistance fighters who were hiding in the nearby forest.

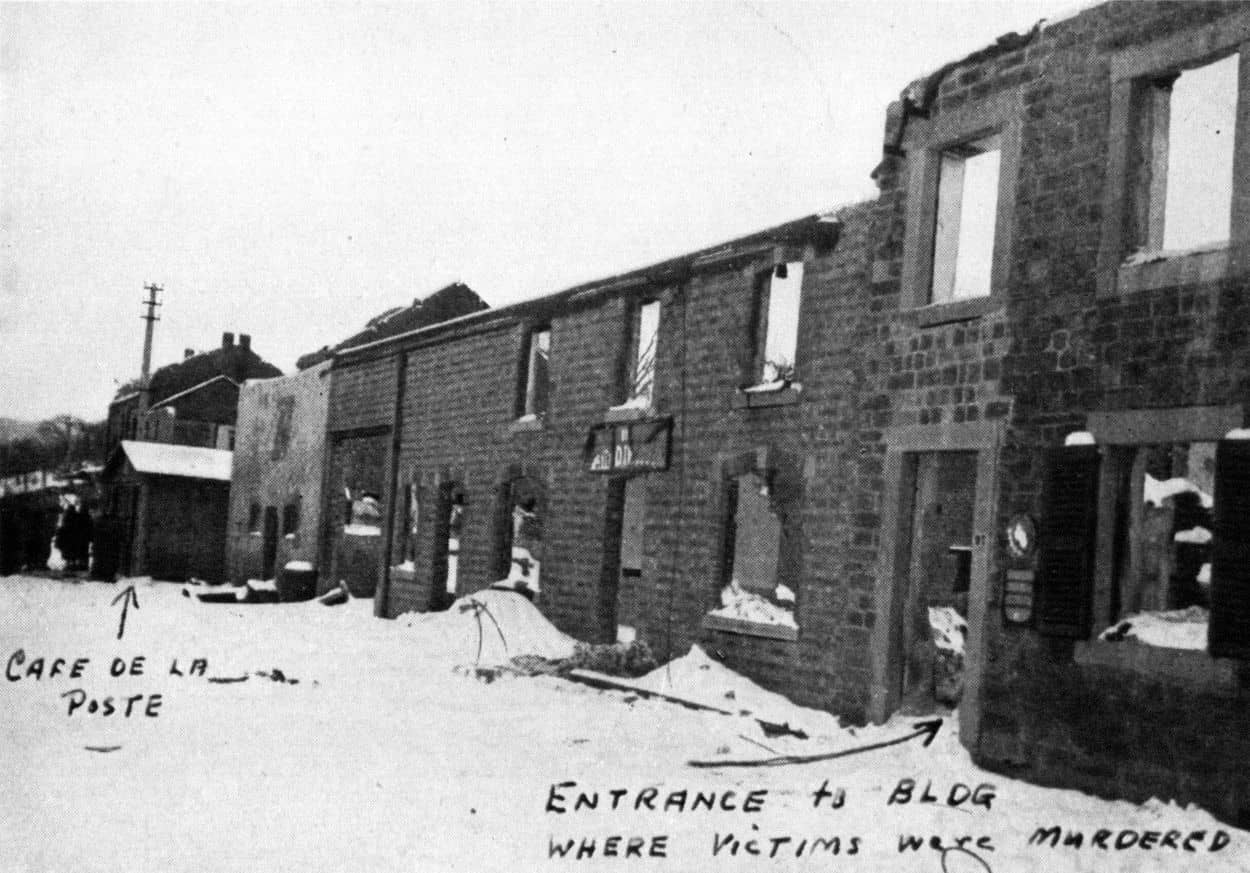

Furious, the Nazi occupiers retaliated by burning down 35 houses on the road from Marche to Bastogne. The town had also defied the occupation forces back in September by exhibiting Belgian flags a few days before the village was first liberated.

However, since re-occupying the town on 22 December 1944, the Nazi forces were back, with a Kommando intelligence unit tasked with finding the resistance members who killed three officers.

Soldiers of the Waffen-SS attached to Kampfgruppe Knittel, on the road to Saint-Vith has Malmedy, during the Ardennes offensive

On Christmas Eve, the Nazi SD unit marched through the town, going house to house, rounding up men for interrogation.

Around 70 individuals were taken to the destroyed Rulkin-Tasiaux sawmill, where, for hours, they tried to extract more information about the resistance fighters. Of course, there were no resistance members among these civilians – many were hiding out in the nearby Ardennes forests.

The interrogators were part of a special secret police unit, known as the Gestapo, which included Nazi collaborators, many of them French-speakers from France, Switzerland and local Walloons. They repeatedly beat the prisoners with bamboo canes until nightfall.

The Gestapo officers then decided to release the older detainees, but kept 33 prisoners aged 17 to 32. They took everything they had: watches, identity cards, papers.

The detained men were led in three rows in front of the Café de la Poste with their hands up.

Then, one by one, they led the prisoners to the adjacent abandoned house to be executed. All of them were blindfolded, led into a cellar and shot in the back of the head.

Heroism

The 21-year-old Léon Praile, the nephew of the mayor of Bande, was among them. He was 15th in the line.

While waiting, listening to the screams, he tried to rally the rest of the fellow prisoners into a frenzy so they could rise and overpower the Gestapo officers. However, there was no reaction; all of them resigned to their fates. They looked "more dead than alive".

Léon knew he was going to do something; he just didn’t know what. When his time came, he was escorted to the blown-out house by the officers.

When he got to within two metres of it, he did the unthinkable. In a swift move, Léon punched the German officer in the face, flooring him, and made a run for it. He was repeatedly shot at by the officers but managed to escape through the thick Ardennes snow in the dark.

"My hands were in the air, so it was easy to hit him on the nose. He fell down and I started running as fast as I could along the road," Léon later testified.

"I saw two officers dressed in black, which forced me to cross the road. There, I jumped over a fence, and that's when the Germans shot at me. But I was already in the fields, I was practically safe."

Léon Praile (left) tells the events to the British officer Sergeant. Lawrie. Credit: IWM

He recounted how he attempted to cross the frontline back into Allied-held territory all night, but the area was crawling with Germans. Having turned back towards the village, he arrived at the house of his uncle, who was the mayor of Bande, in the early hours of Christmas Day'44.

"It was dawn when I entered my uncle's house, where I hid in the hayloft, well hidden in a corner. I stayed there until 10 January, when the Germans left. On 11 January, the British arrived. I told them what had happened and, with my uncle, who was the mayor, we discovered the 34 bodies."

The Nazis fled Bande on 10 January. A unit of mainly Belgian paratroopers from the British SAS, led by Lieutenant Charles Radino, rolled into Bande on 11 January. They were later joined by the 9th Anglo-Canadian Parachute Battalion.

After they arrived in town, Léon informed the Allied soldiers about the massacre. He helped them, along with a priest called Father Musty, to find the bodies hidden in the cellar of the abandoned house under a wooden pane.

Father Musty indicates the whereabouts of the corps to the Allied officers.

Father Musty had arrived in Bande just days before the Germans retook it with a class of students on an excursion. They had stopped in Bande to rest until their trip was cut short by the return of the Nazis.

Four of his students were among the 34 assassinated on Christmas Eve. On the night, he had tried to go to the abandoned house to save them but was pushed away by the German officers who pointed a gun at his chest and said: "You black crow, get out."

It also emerged that a day later, on Christmas Day, another two young people from the village of Roy were taken to the same house and executed. The bodies wouldn’t be discovered until two months later.

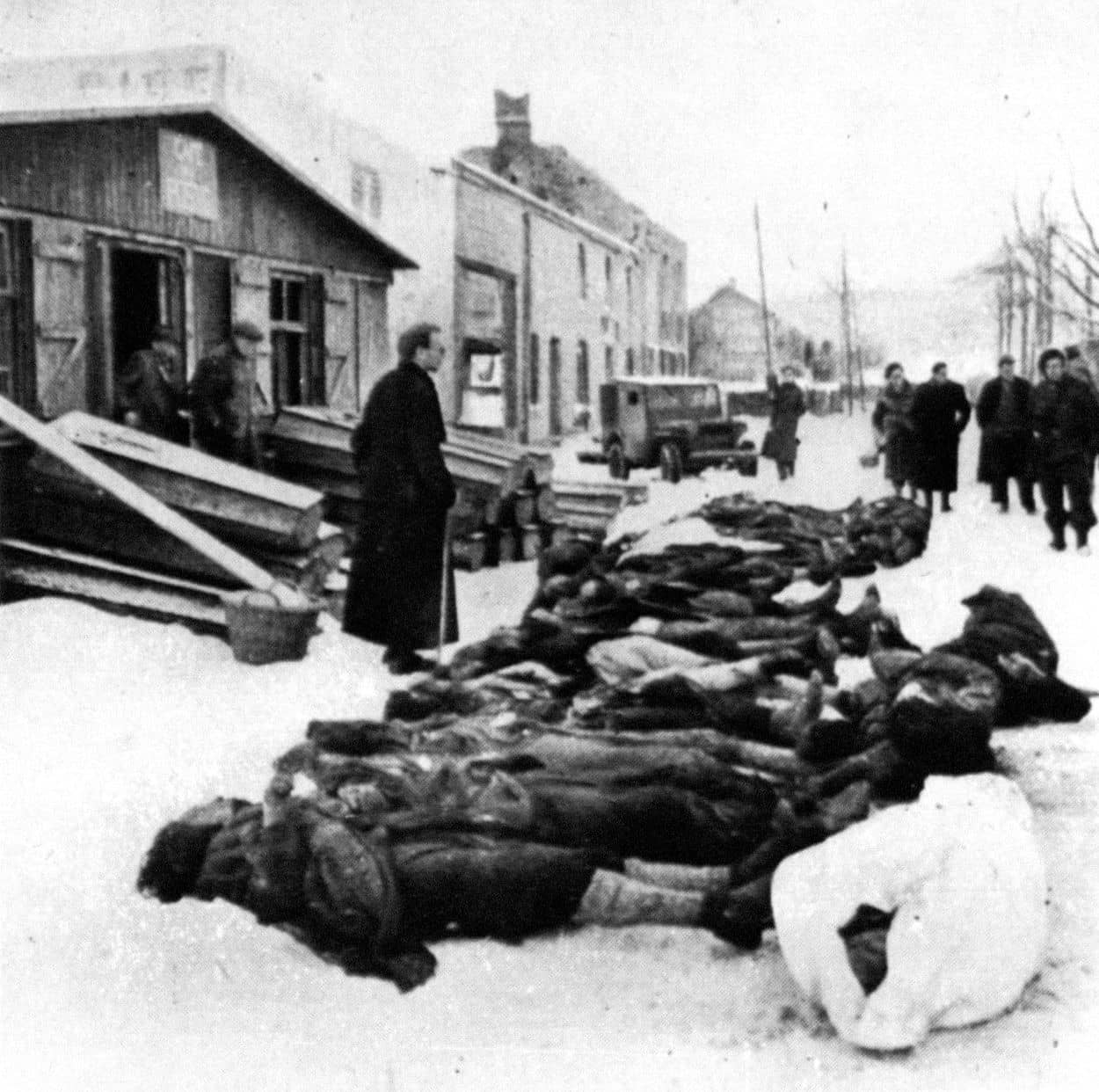

The other 34 frozen bodies murdered on the 24th were pulled out of the fatal cellar and lined up on the street outside the Cafe de la Poste.

Father Musty in the background with the bodies of the victims

The commander of the 9th Parachute Battalion uttered a cry, “Why?” when seeing the massacred bodies for the first time. He then turned around to Father Musty.

"Father, I am going to make all my soldiers walk past these 34 corpses. I want them to realise that this is real. It will appear in the American press, people will shrug their shoulders and say it's propaganda, that it's not possible for such a thing to happen. I want them to come and see that all this really happened."

Legacies

On January 18, 1945, a collective funeral was organised, while in June 1948, a memorial to the fallen was inaugurated.

While Leon died in 2004, last year, Belgium marked 80 years since the Battle of the Bulge.

For the commemoration, French-speaking Belgian broadcaster RTBF met the brother of André Gouverneur, who was among the victims, aged just 17.

Michel Gouverneur, who was 8 at the time, recounted his memories to the public broadcaster last year.

"It took us a while to understand. Because I think it was a tradition in our Ardennes region: there were some things you didn't tell children."

Only one perpetrator was ever tried for the crimes – a Swiss man called Ernst Haldiman, who was arrested in Basel in 1948 after being identified as one of the executors.

He had joined the SS in France in November 1942, and in 1944, his unit was integrated with other intelligence units, which led him to the town of Bande. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison and released on parole in 1960.

The story of Bande is one of the many atrocities at the hands of the Nazis and their Axis allies during the Second World War. Today, its memory remains a grim warning against allowing the seeds of fascism to bloom.

A documentary in French from 1994 by RTBF includes the testimonies of both Leon and Father Musty about the Bande massacre.

From the memorial of the massacre in Bande