In November 1944, one of the few German V-1 rockets aimed at a recently liberated Brussels hit Rue de l’Ermitage in Ixelles. It scythed through seven houses, killing 12.

The soundwave it generated shattered the monumental stained glass in the stairwell of the 1894 Hôtel Solvay, some 250 metres away on Avenue Louise.

This was the first serious damage suffered by one of the major townhouses built by the architect Victor Horta. Peacetime, however, would bring an even greater threat to the vast and ornate buildings of fin-de-siècle Brussels.

Too old to serve their original purpose, they were too unwieldy to adapt to new functions, and their faded charms were too recent to be accepted as monuments worthy of protection.

Eight blocks down Avenue Louise from the Solvay house at number 520, a time bomb was ticking. In December 1943, industrialist (and Le Creuset cookware co-founder) Octave Aubecq had died, leaving to his son the magnificent mansion Horta had built for him decades earlier. Five years later, the house was sold to developers who planned to demolish it and build flats in its place.

News of the project would reach architect Jean Delhaye, Horta’s last assistant and himself a developer of modern flats. Delhaye worshipped Horta, regarding him as one of the greatest architects in history – a highly eccentric view at that time. He appealed to the rich and powerful to save the building, and when this failed, he browbeat the authorities into subsidising a salvage mission.

Only some windows, ironwork and stones from the facade of the Aubecq mansion could be saved for storage, and the authorities promised a partial reconstruction at a later date. This hollow victory was the beginning of a journey for Delhaye. He would spend the rest of his life defending Horta’s legacy, explaining his genius and personally saving most of his major townhouses.

Amid the frenzy of Brussellization, the conversion of the city to fast car travel and office-building, and in the face of hostility from heritage watchdogs fixated on classical, baroque and medieval architecture, Delhaye fought over decades to rehabilitate the creations of the Art Nouveau generation of 1900.

Related News

- Brussels by air: How the city changed in 40 years

- Echoes in bronze and glass: Inside the lavish Revival of Belgium's Art Nouveau and Art Deco heritage

- The meaning of Brusselization

- Layers of time: How digging for a car park revealed the soul of Brussels

- The Art Deco disciple under Victor Horta's wing

If such buildings are now seen as quintessential Brussels, it is thanks to this disciple of Horta. Restoring their colours in a city now being engulfed in grey concrete, he showed how they could be anchor attractions in an alternative form of urban renovation.

An exhibition on the life and work of Jean Delhaye runs until March 29, 2026, at Ganshoren town hall. Housed in an exquisite brutalist former architect’s practice, it uses one man's life to tell the story of the 20th-century-built environment of Brussels, from Art Nouveau through modernism to preservation and rehabilitation amid the upheaval of war and the postwar reconstruction of the city.

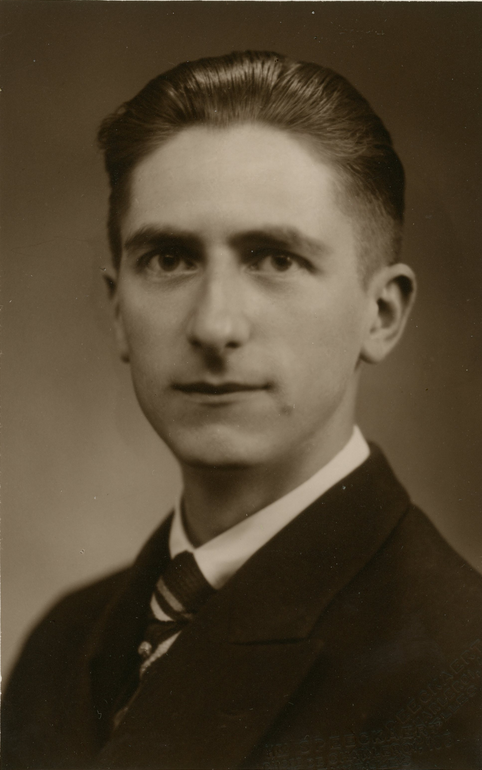

Jean Delhaye, a Victor Horta disciple and saviour of Art Nouveau in Brussels

Delhaye was born in 1908 in Vodelée near the border with France and as a child, spent the First World War in the Puy-de-Dôme, where his French uncle was a mining engineer. Finishing his schooling in Brussels, in 1929, he started a four-year course in architecture at the Royal Fine Arts Academy, where he caught the eye of its director, Victor Horta, then militating for reform of the training and outlook of the profession.

Horta had spent much of the First World War in the US, where he was captivated by the potential of system-building at large scale. He returned to a Belgium starved of skilled labour, capital and materials, where the appetite and vast private budgets for bespoke artworks like the Solvay and Aubecq mansions were gone.

Turning his back definitively on the nouille, or whip, style that made his name, he focused on public-sector works, sublimating decoration to a minimum and focusing on the efficient execution of the brief. This work during the second half of Horta’s career was to heal two deep urban wounds in the centre of Brussels left by unfinished work on the modernisation of the city’s transport.

In 1922, at age 61, Horta began work on a new Palais des Beaux-Arts, now Bozar, which would fill a cavernous hole left between the Brussels Park and the new Rue Ravenstein, a curving ramp built on concrete stilts. As at the Maison du Peuple of 1899 (Horta’s lost masterpiece, thanks to its infamous demolition in 1965), it was an unforgiving site on a steep slope.

Both buildings called for a large performance hall to be crammed in a tight space with many other functions. Thus, at the Maison du Peuple, Horta hoisted the salle des fêtes to the top of the building, while at the Bozar, he buried the Salle Henry Le Bœuf in the basement. Such mastery of space convinced Delhaye he must either work for Horta or quit the profession.

In 1934, Delhaye joined Horta’s practice and became an assistant on the now septuagenarian architect’s final challenge: crafting a train tunnel and Central Station for Brussels in the crater left by demolitions when the project stalled after the First World War.

Residence Basilique

As work began at the site in 1937, Delhaye started building his first apartment building on a corner site in Ganshoren, behind the gargantuan project to create one of the world’s largest churches, the National Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Koekelberg.

The Résidence Basilique, completed in 1938 (32 years before the actual basilica), was a sleek and sober seven-storey block. It is now a protected monument, an example of late Art Deco as it slid towards the postwar restraint of modernism.

Aimed at the luxury end of the growing market for flats rather than houses, the mosaic floors and curved metalwork of its arresting stairwell were nods to Horta’s flamboyant early creations. Applying his master’s examples, both decorative and structural, to the problem of modern living would absorb Delhaye in the years to come.

Prisoner of war

Mobilised in 1939, Delhaye joined the 3rd Regiment of Cyclist Riflemen (or Diables Noirs) and was captured in Flanders during the German invasion of May 1940. He was held as a prisoner of war at Stalag XA in Schleswig.

On display at the Ganshoren exhibition is a rambling letter from February 1941 supplied by Horta to Delhaye’s wife to try to secure his release. Emphasising his status as a baron, it observes that work on the Central Station had resumed with the approval of the occupying authorities and that Delhaye’s absence could delay its execution.

A poignant follow-up letter from Horta to Delhaye betrays the petulance of old age and failing health, both defiant and self-pitying. While in captivity, like the previous generation of architects who had spent the war in exile preparing for the peace, Delhaye had started work on a manual for builders of apartment buildings. Prefaced with an homage to the genius of his master, he sent Horta a draft from the camp.

Jean Delhaye's WW2 deportation card

Horta was touched by the elegy, but most of his reply is taken up with concern that he was being sidelined from the Central Station project because of his age, complaints about his health and the inconvenience of Delhaye’s absence.

Horta signs off, asking if perhaps the Germans could spare Delhaye for a couple of weeks. Despite this jokey, even callous, attitude towards an underling held captive by the enemy, the letter betrays a conspiratorial and familiar tone that shows a bond between the two men.

A warmth of personal feeling that would sustain Delhaye in the decades ahead. It would fuel a mission to restore not only Horta's houses but his reputation as an architect and that of the derided architectural landscape from the dawn of the 20th century.

Horta defamed

In December 1936, architectural trade journal Bâtir published an interview with Stanislas Jasinski under the title ‘Destroy to Create’. The modernist architect argued that the squat, obsolete mansions of 1900 Brussels should give way to tall apartment buildings, notably along major streets such as Avenue Louise.

In the same issue, critic Pierre Gilles took aim at the Aubecq mansion: “A pampered building that unrepentantly recalls those airy-fairy years.” The creation of “an aesthete-architect”, its “drooping floral lines” resembled faded coastal casinos and the work of humorous illustrator Albert Robida, he wrote. As for neighbouring mansions in the eclectic style of the period, “with their consoles, caryatids, balustrades, imitation columns and gables, they look like old dears caked in makeup.”

Hôtel Aubecq 1948

A decade after this campaign of defamation, a hoarding was erected outside the Hôtel Aubecq, announcing it would give way to “a building of quality”, an apartment block designed by Jasinski. Delhaye alerted the Horta Committee, co-founded by him, demanding they petition heritage regulator the Royal Commission for Sites and Monuments (Commission Royale de Monuments et Sites/Koninklijke Commissie voor Monumenten en Landschappen, CRMS/KCML) for a protection listing.

The committee refused, arguing that a plea on behalf of “a work of folkloric interest” would discredit their activities. An incredulous Delhaye began his own campaign.

Delhaye wrote to former US President Herbert Hoover, who had known Horta, asking for his backing to convert the Hôtel Aubecq into an American cultural centre for Brussels or to dismantle it and ship it, with all its bespoke furniture and fittings, to the United States. There was no reply.

Delhaye may have misread the room by enclosing with his letter to the Republican a fierce article defending the house from “vulture” capitalists clipped from Le Peuple, the mouthpiece of the Belgian Socialist Party.

However, there was no real precedent for motivating support for architecture of such a recent period. CRMS guidelines excluded protection for buildings by artists dead for fewer than 50 years – and Horta passed away in 1947.

Through trial and error, Delhaye honed his approach. The Aubecq house was demolished in 1950, but he secured a grant to select the most representative 650 stones of the facade and place them in storage.

Aubecq demolition 1950

From triumph to disaster

Horta’s other houses, built like the Aubecq for a vanished rentier society, remained at threat as Brussels was remodelled for express car travel, international corporations and tourism starting with the run-up to the Exposition of 1958. Delhaye would use the momentum of what would later be decried as Bruxellisation to fund his mission.

His well-received book, L'Appartement d'aujourd'hui, published in 1946 had become a reference for apartment-building and he was in demand. Delhaye built extensions to the Art Deco Résidence Basilique in Ganshoren in a distinctive bulbous style more suited to the 1950s and in tune with the new, curvy aesthetic of the all-conquering motor cars of the period.

He replaced large mansions to the east of the city on the fringe of what would become the European Quarter. He used the proceeds to restore the Horta-designed house on Avenue Palmerston next to the extraordinary metal facade of the 1895 Hôtel Van Eetvelde, a showcase for the fabulous wealth of the Congo venture.

The Palmerston house became Delhaye’s family home for two decades from 1958 (it is now, fittingly, the reception area for LAB·AN, a space for the promotion of Art Nouveau opened by the Brussels region in 2023 and which includes the newly-restored Hôtel Van Eetvelde).

In 1959, Delhaye acquired the 1896 Hôtel Deprez-Van de Velde opposite, and the following year added the 1901 Dubois mansion in Avenue Brugmann and bought Horta’s own former home in Rue Américaine from the architect’s family. He immediately set about restoring the house, built in 1898 as a life-size manifesto for Horta’s Art Nouveau period, and planned its future as the Horta museum and treasure house for his master’s papers (including his precious memoirs) and plaster models, as well as whatever material he could salvage from the demolished buildings.

In 1963 came Delhaye’s first real triumph when the government agreed to its protection as a monument, the first such 19th century building to receive this honour.

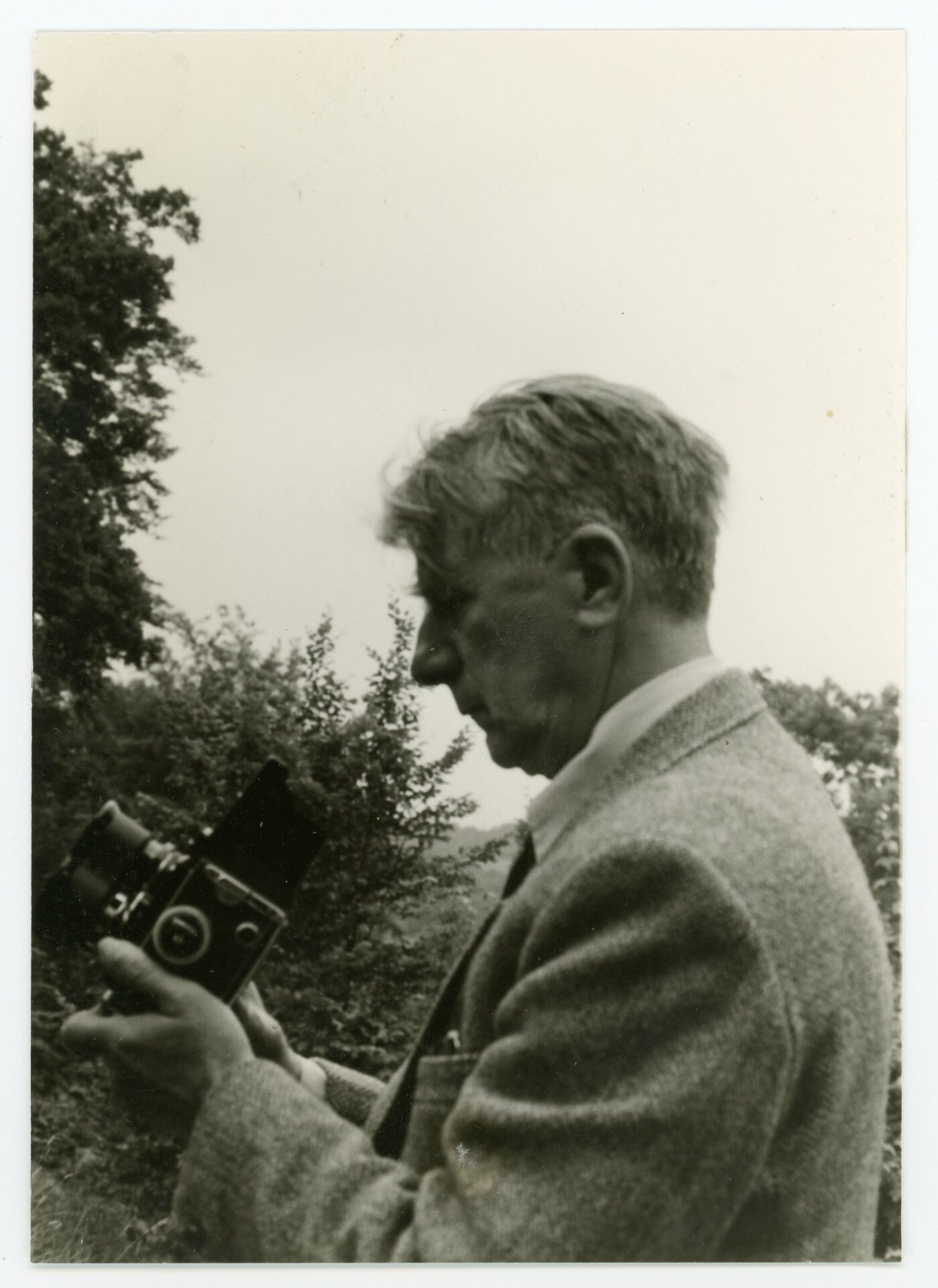

Jean Delhaye on the stones of the demolished Maison du Peuple

Disaster soon followed as news came of plans to demolish the Maison du Peuple, Horta’s 1895 masterpiece. Delhaye appealed once again to the forces of capitalism, writing to the head of German conglomerate Krupp to demand its intervention. The spiritual home of Belgian socialism was a poor fit for the company’s cultural outreach funds and Herr Krupp’s secretary replied with a no.

There was a brief possibility that the building’s walls could be retained, making it the first in what would later become a Brussels speciality: facadism. The preservation campaign had the backing of a petition from more than 700 foreign architects and experts.

This caught the attention of the Belgian media, and Delhaye was invited to defend the building on television. “Plenty of people walk past that facade every day without finding anything remarkable. What's beautiful about it?” the reporter asked.

Dirty, poorly maintained, its original colours painted over, it was hard to defend the Maison du Peuple’s merits to a lay audience. Delhaye made a dry academic show of it, explaining how the lines of the facade expressed the interior plan.

With no precedent for public money stepping in to save a relatively young building from a lucrative private property deal, demolition went ahead. Delhaye was a daily visitor to the site, taking hundreds of photographs and moving dismantled fragments of stone and ironwork to the garden of the house in Rue Américaine.

Lessons in crowd-pleasing

Delhaye drew several lessons from the Maison du Peuple affair. The scandal of demolition had moved the tide of public interest in Horta’s favour and spurred international esteem for Belgian Art Nouveau. It had vindicated his decision to acquire the major townhouses, but the TV interview demonstrated the need to restore them to their original colourful glory. If they were to become crowd-pleasers, a show-not-tell approach was required.

Further vindication followed in 1972 when a working group of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe on urban renovation concluded that restored historic monuments could be the catalyst for renewal of surrounding neighbourhoods.

That same year, the government listed 12 Horta buildings for protection and in the following years, other creations by his contemporaries and rivals were added to the list of Brussels monuments. Protections were accorded to Paul Hankar’s 1893 home in 1975; a flurry in 1976 added Josef Hoffmann’s 1905 Palais Stoclet, Jules Brunfaut’s 1902 Hôtel Hannon and the 1904 home of Paul and Lina Cauchie.

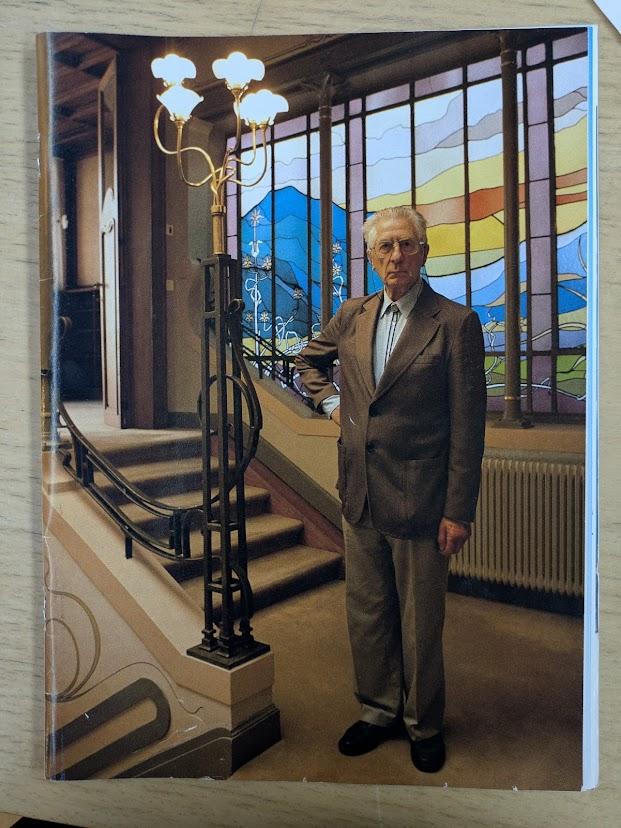

Jean Delhaye

The process accelerated through the 1980s to cover less well-known architects such as Ernest Blérot, Gustave Strauven and Octave Van Rysselberghe. By 1984, Delhaye's campaigning, joined by citizen pressure groups such as ARAU and IEB, had finally motivated the government to take an active salvage role and Horta's 1905 Waucquez wholesale draper's store was acquired by the Belgian state and restored to create the Comics Art Museum.

These days, the design language of Horta’s Art Nouveau period is written across the Brussels region's public-facing infrastructure: bus stops and the interiors of newer STIB/MIVB metro carriages carry the whip motif. Along with the Palais Stoclet, four of Horta’s major townhouses are UNESCO World Heritage sites: Solvay, Van Eetvelde, the Horta house and workshop, and the Hôtel Tassel in Rue Paul-Émile Janson, the last of the houses acquired by Dehaye, in 1976.

Explaining Art Nouveau

By the 1970s, Delhaye understood that to thrive, Horta’s houses needed to be objects of desire, seducing the public, rather than just eliciting respect among architects for the fulfilment of a long-forgotten brief. Instead of explaining the dusty geometrical prowess, he needed to be able to wave a hand and say, “Look at that!”

These days, the Hôtel Tassel, with its tiny backyard and its vase-like interior lit through lavish stained glass, feels like a continuous three-storey reception area. There is no need for ornaments as it is the ornament. The house would become familiar to Gen-X students as the cover of American alternative rock band Mazzy Star’s debut album, She Hangs Brightly.

“The moment I heard it was for sale I knew I had to have it,” a proud Delhaye said, posing for a colour portrait in the house during an interview in 1991. “Despite its historical value, the property was in a disastrous condition, a shadow of its former glory.” Delhaye told Sphere, Belgian airline Sabena’s in-flight magazine, that like Horta he had mastered many skills himself for the long restoration: panelling, parquetry, fresco, wrought ironwork and mosaic flooring, stained glass.

Jean Delhaye

"I have no idea how much these houses are worth these days…Anyway, their real-estate value isn't important. I don't have the slightest intention of selling. And my children have formal instructions to follow suit." To this day, the Delhaye family still owns three of the mansions: the Deprez-Van de Velde and Dubois houses and the Hôtel Tassel.

Emulate, not copy

Delhaye’s own buildings are peppered with homages to Horta. Railings lining the long flight of steps at the entrance to his 1959 modernist apartment building on Avenue de Villegas opposite the exhibition venue reproduce Horta’s whip motif.

But he never wanted to copy his master’s buildings: “That would have been the wrong ambition, madness…Horta's style was his own, something seldom achieved in the whole history of architecture. It was close to perfection.” In a handwritten ‘CV’ from 1989 held by the CIVA archives, Delhaye, now 80, listed his own principal creations and completed it with a self-effacing epitaph: “Please note that the architect Jean Delhaye, student, colleague and disciple of Victor Horta spent most of his life defending the creation of his master, bringing many buildings back to life.”

Yet Delhaye didn’t lack ambition. On the contrary, rather than copying his style, Delhaye wanted to emulate Horta’s skill in mastering awkward sites.

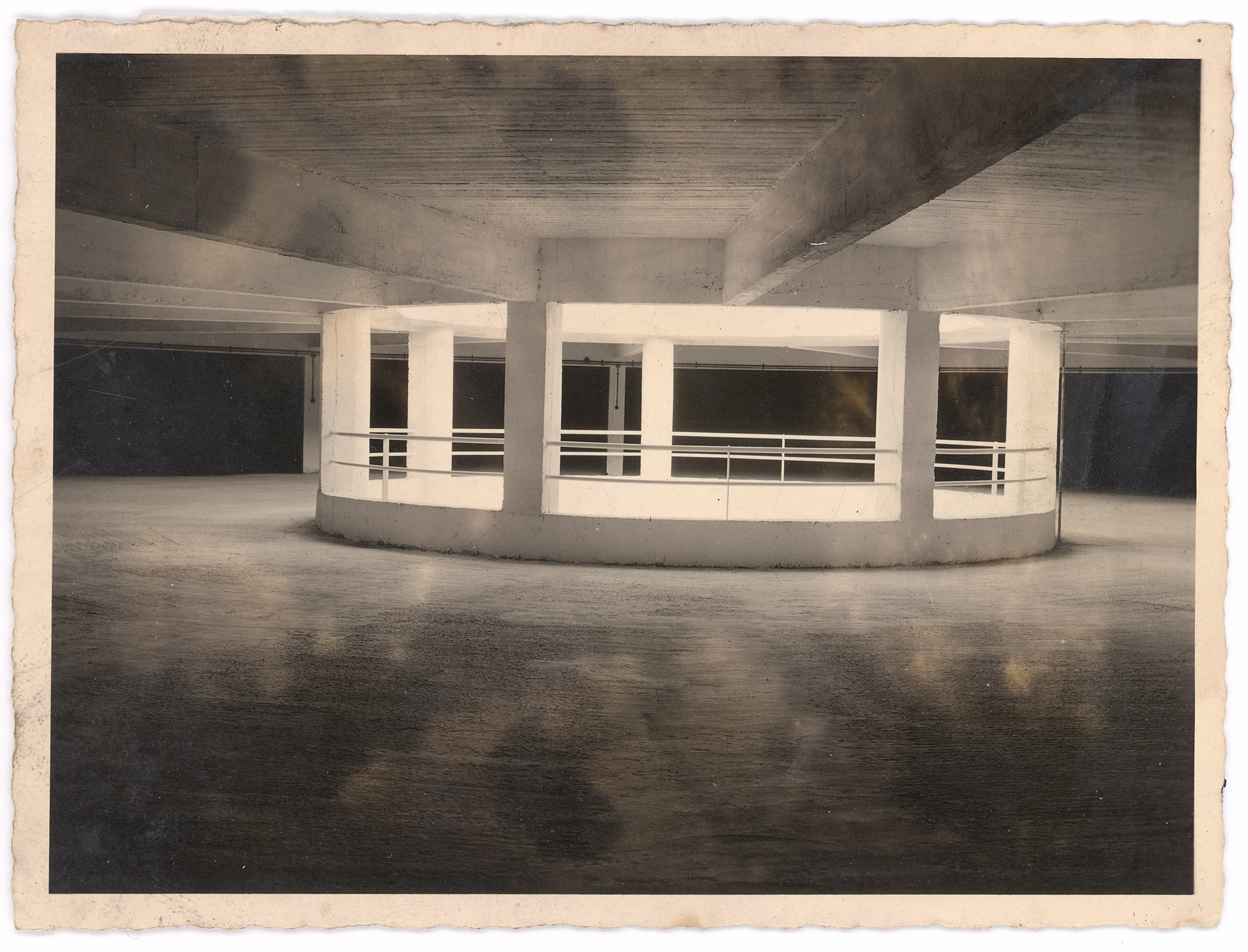

The exhibition displays the promotional leaflet for his 1955 Coliseum Residence, situated on a sharp slope on Chaussée de Boondael opposite Ixelles Cemetery (where Delhaye had designed the Horta family tomb pro bono in 1950). It crams in a car workshop, apartment building and 12-metre high circular parking garage with a diameter of 39 metres that rises just 2.75 metres above ground level by taking advantage of the change of level.

A hundred heated and ventilated car-sized lockers were divided over four storeys. It is the height of the mid-century-modern auto-technology cult satirised by Jacques Tati in films such as Mon Oncle, Playtime and Trafic.

The product of a bygone and rather derided age, in its 70th anniversary, it is no more precious an artefact today than Horta’s demolished gems were in their twilight years, a dangerous age for any building.

Hanging garden of Horta

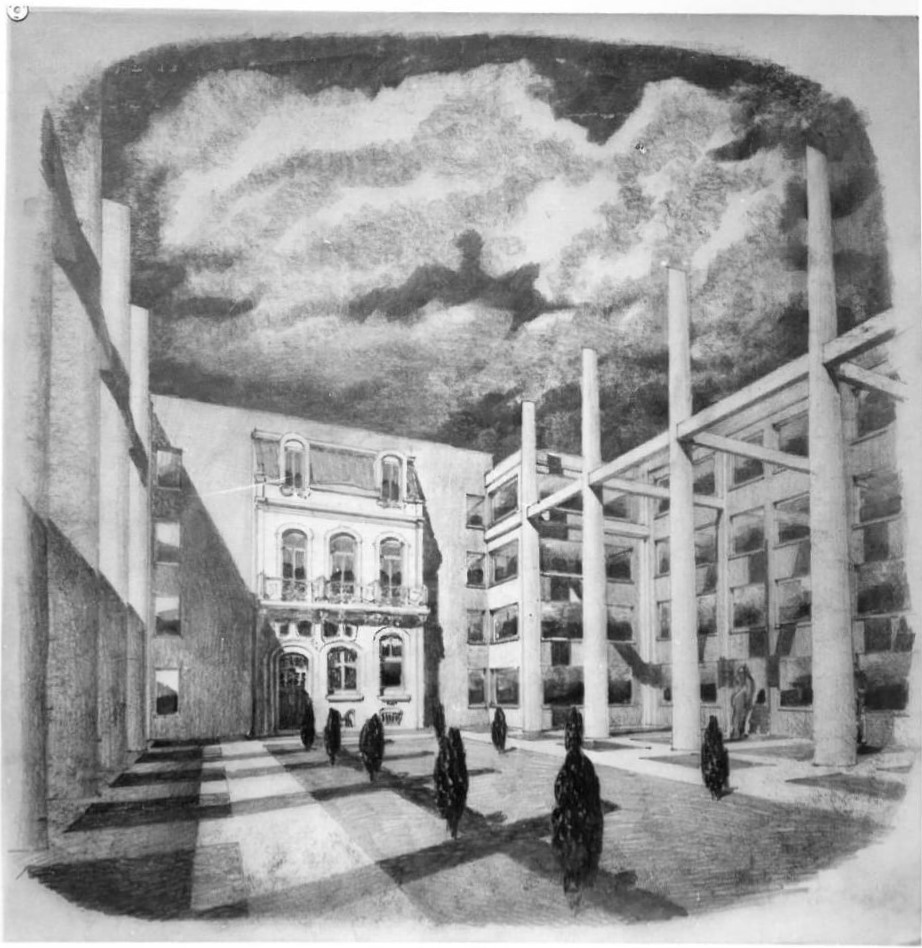

As an exercise in stacking human beings and cars in a tight space, Coliseum was a dry run for Delhaye’s most ambitious project. In 1969, he published his proposal for a new Museum of Modern Art for Brussels, to fill a ravine to the south of the Place Royale, a belated twin to the Bozar, inserted within a corresponding ravine to its north by Horta in the 1920s.

A concrete facade would be inserted between the Old Masters Museum and Notre-Dame des Victoires au Sablon on Rue de la Régence, its broad modernist horizontal lines crowned with flying buttresses in deference to the medieval church.

A vast, airy interior with natural lighting aimed to move on from traditional picture galleries, exploring the “interpenetration of influences between disciplines,” placing paintings amid spaces for sculpture, music, furniture, theatre, dance, cinema and of course architecture in the form of a 1900 winter garden built by Horta for the Cousin mansion in Chaussée de Charleroi and just dismantled by Delhaye.

Delhaye J. - Coliseum - Boxes et Station 1954-1956

Drawing on his experience at the Coliseum building, Delhaye proposed to bury a spiral car park deep in the valley below the building. On the roof, the main attraction, an open-air hanging garden upon whose walls he would hang the remaining facades of the Maison du Peuple and the Hôtel Aubecq.

Delhaye’s captivating plans for a museum encompassing modern design from Horta onwards, on display at the Ganshoren exhibition, were never built. The Aubecq stones, then in storage at Buda to the north of Brussels, moved to Saint-Gilles, then Uccle, then a barracks in Namur. A 1979 proposal to rebuild the facade next to Place Royale was blocked as disrespectful to the neoclassical surroundings.

In the 1980s, a project to rebuild the house against the back wall of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris came and went (most of the Aubecq’s furniture and fittings are on display at the Orsay), and the stones moved from depot to depot. Their saviour Delhaye died in 1993, the centenary of the invention of Art Nouveau. He never got to see the Aubecq facade rebuilt. But 75 years since he lovingly rescued them, nobody has.

Plans for a Modern Art Museum by Jean Delhaye which did not come to fruition

The property of the Brussels region since 2001, the stones from the Hôtel Aubecq were displayed in 2018 at the former Citroen garage and future Kanal Museum in an exhibition aimed at prompting the question ‘What now?” An answer came in July 2025, soon after the Cousin winter garden was finally re-erected at the Royal Museum of Art and History in the Cinquantenaire Park.

The region announced the signature of a public-private-partnership to use the Aubecq stones as a training exercise for the heritage restoration sector: put them on public display, laid out flat, and then re-erect the facade, or lay it flat, somewhere, at some point in time using a budget that doesn’t currently exist.

Amid the squeeze on funding for the acquisitions needed to draw visitors, the future viability of the Brussels Region’s Kanal Museum is uncertain. Due to open in November 2026, it needs star attractions it can’t afford.

As a space dedicated to the interdisciplinarity of the arts, overturning traditional display practices, it is the spiritual successor to Delhaye’s dream of a cutting-edge museum picking up the story of modern art with his idol Horta. Perhaps as a tribute to the man who saved Brussels and to draw the crowds, the region could finally put an end to the Hôtel Aubecq’s limbo and hang it on one of the Kanal’s walls. Permanently and cost-free.