As the capital of Belgium and the heart of the European Union, Brussels now has the questionable honour of being able to call itself the city with the dirtiest public toilets in Europe – and its efforts to clean up its act are falling short.

With fewer than five public toilets per 100,000 residents, Brussels has one of the lowest number of toilet facilities per capita in Europe.

What's worse, the city scored 9.71/10 on Showers to You's "dirtiness index," which is based on analysis of over 19,000 Google reviews of public toilets, examining average toilet ratings and the number of keywords in reviews synonymous with "dirty."

With an average toilet rating of 3.4/5, Brussels falls below the European average of 3.7 for cleanliness – highlighting ongoing hygiene concerns. Additionally, one in five reviews (22.1%) used words like "dirty" or "smelly" to describe the city's toilets.

"This poor ranking is very bad for the reputation of Brussels, which could have a huge impact on tourism," researchers Lien Maes and Lucas Melgaço (VUB), who published a study called 'Public Toilets in Brussels' Public Spaces: Necessity or Nuisance?', told The Brussels Times.

"The authorities may look at public toilets only as a cost, but they should also take into account the reputational cost of their city being considered so dirty," Melgaço said.

The right to basic hygiene

In their research, Maes and Melgaço found that the general state of public toilets in Brussels was "bad, very bad". The main issues they cited were the small number of available toilets, and the low frequency of cleaning.

"They are cleaned twice a day, but considering that they are used by hundreds, if not thousands, of people every day, that is just not enough," said Maes. "When the cleaner arrives in the morning, five or six people are already waiting."

It is not just a matter of providing the physical infrastructure, but also of ensuring that the few that are installed function properly, they both stressed.

Public toilet in Brussels. Credit: City of Brussels

The City of Brussels is aware of the issue, and is working to provide the public – from tourists discovering the city to homeless people – with clean spaces for basic hygiene. For this reason, former municipal councillor for public cleanliness Zoubida Jellab (Ecolo) implemented a "toilet plan" for the city.

Now, her successor, Anas Ben Abdelmoumen (PS), is continuing her efforts, he told The Brussels Times.

"We remain committed to public toilets. In the 2026 budget, we are allocating €300,000 for the replacement of two public toilets," he said, explaining that the installation cost of just one public toilet is €150,000.

"These are quite large sums, but we continue to believe it is important to invest in this because it is about providing basic hygiene for people," said Ben Abdelmoumen.

Slow growth

At the end of 2025, one completely new public toilet was installed at Square Marguerite in the European quarter, and two others were replaced.

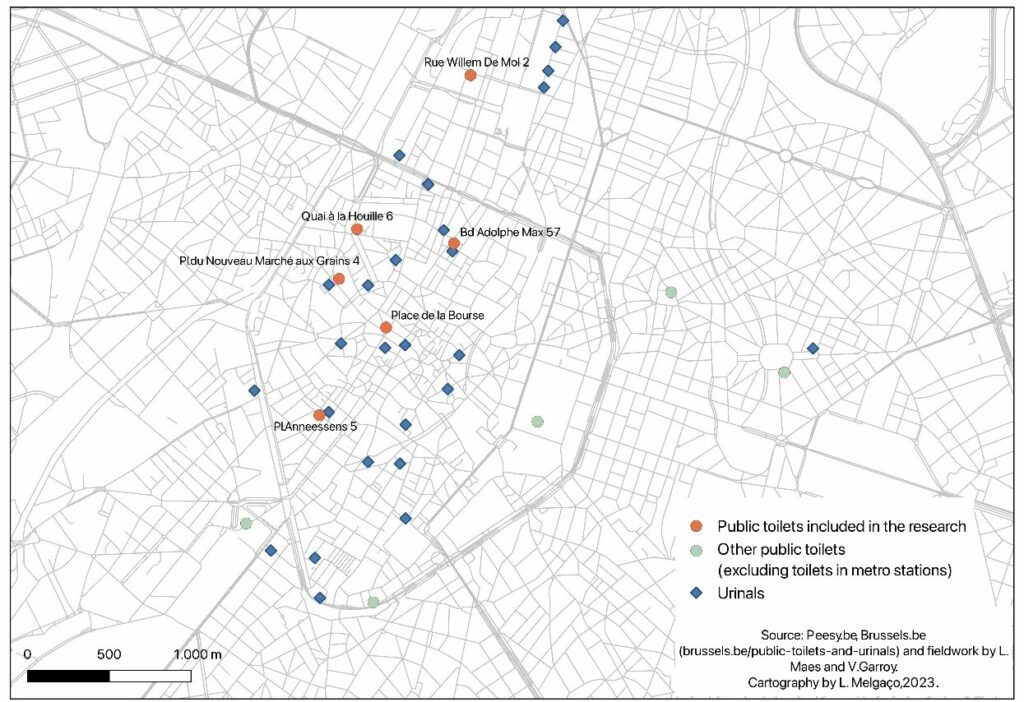

Currently, the City of Brussels provides 12 public toilets and 22 urinals on its territory – completely free of charge. More toilets are added gradually, but Ben Abdelmoumen admits that the high investment costs and maintenance efforts mean that the process is slow-going.

Without an overarching policy from the Regional Government, the City of Brussels is the only one of the Capital Region's 19 municipalities to implement its own approach.

Map showing other public toilets and urinals outside the limits of the City of Brussels to make clear the considerable difference in the offer of these two types of facilities. Credit: Lucas Melgaço

"As the largest municipality in Brussels, which includes the city centre where there are a lot of tourists, as well as homeless people, it is important to set up public toilets," Ben Abdelmoumen said.

In addition to the historical city centre in the Pentagone/Vijfhoek, the districts of Laeken, Neder-Over-Heembeek, Haren, the areas around the Avenue Louise (including Bois de la Cambre), and the European Quarter are also part of the municipality's territory.

"Obviously, the toilets in the city centre see much more use than those in Neder-Over-Heembeek. The need is definitely greater in the middle of the city," he added.

Not in my backyard?

Importantly, Maes and Melgaço found that while many people agree on the importance of having access to sufficient public toilets, they would rather that those toilets are not installed in the districts where they live and work.

"They are generally not very popular with locals, and merchants do not want them in front of their shops. There is a bit of a 'not in my backyard' attitude towards them," Melgaço said.

That only makes it more difficult for the municipality to find a suitable place for public toilets, because they need to take other factors into account as well. "It needs water and electricity, for example. You cannot just plant it anywhere you want," Maes explained.

While the researchers do not deny that public toilets can bring nuisance – from smells and dirtiness to drug dealing – to the area they are in, they stressed that removing them is "the worst possible solution."

In order not to have the nuisance, the solution is to address the bigger societal problems, such as homelessness and drug crime, at the root of the issue. "If you want to deal with drug consumption, maybe the solution is investing in safe places for people to consume drugs. Not self-cleaning toilets."

Additionally, the more public toilets there are, the less pressure there is on each of them, they argue.

Photograph taken at Quai à la Houille on 2 February 2020: Credit: Lien Maes

To make up for the lack of stand-alone toilets across the city, the Brussels authorities have invested in a network of "hospitable toilets" in hotels, bars and restaurants that make their facilities available to everyone – free of charge, no consumption required.

"For 2026, we have a €60,000 budget for this. Establishments that open up their toilets receive a €1,000 subsidy and receive assistance from the city authorities in terms of maintenance costs," Ben Abdelmoumen said.

Currently, 54 establishments in Brussels are part of this network – recognisable by the 'I am a hospitable toilet' sticker on their door or windows. "The main advantage of this is more social control. There is less risk of vandalism or drug use," explained Ben Abdelmoumen.

Additionally, 13 of the City of Brussels' public buildings (such as libraries, sports halls, and administrative buildings) are also part of that network. The challenge, Ben Abdelmoumen admits, is making people aware of this network and of the impact people themselves can have on their environments.

"Brussels is not dirty, Brussels is being dirtied," he stressed. "Public toilets are not naturally dirty. We cannot deny that they are often dirty, but that is because people see them as the ideal place to commit vandalism. They abuse this crucial infrastructure to do things that should not be done in public."