Last night, in a ceremony heavy with academic formality and light on spectacle, one of Belgium’s quietest intellectual enterprises received one of its loudest international endorsements.

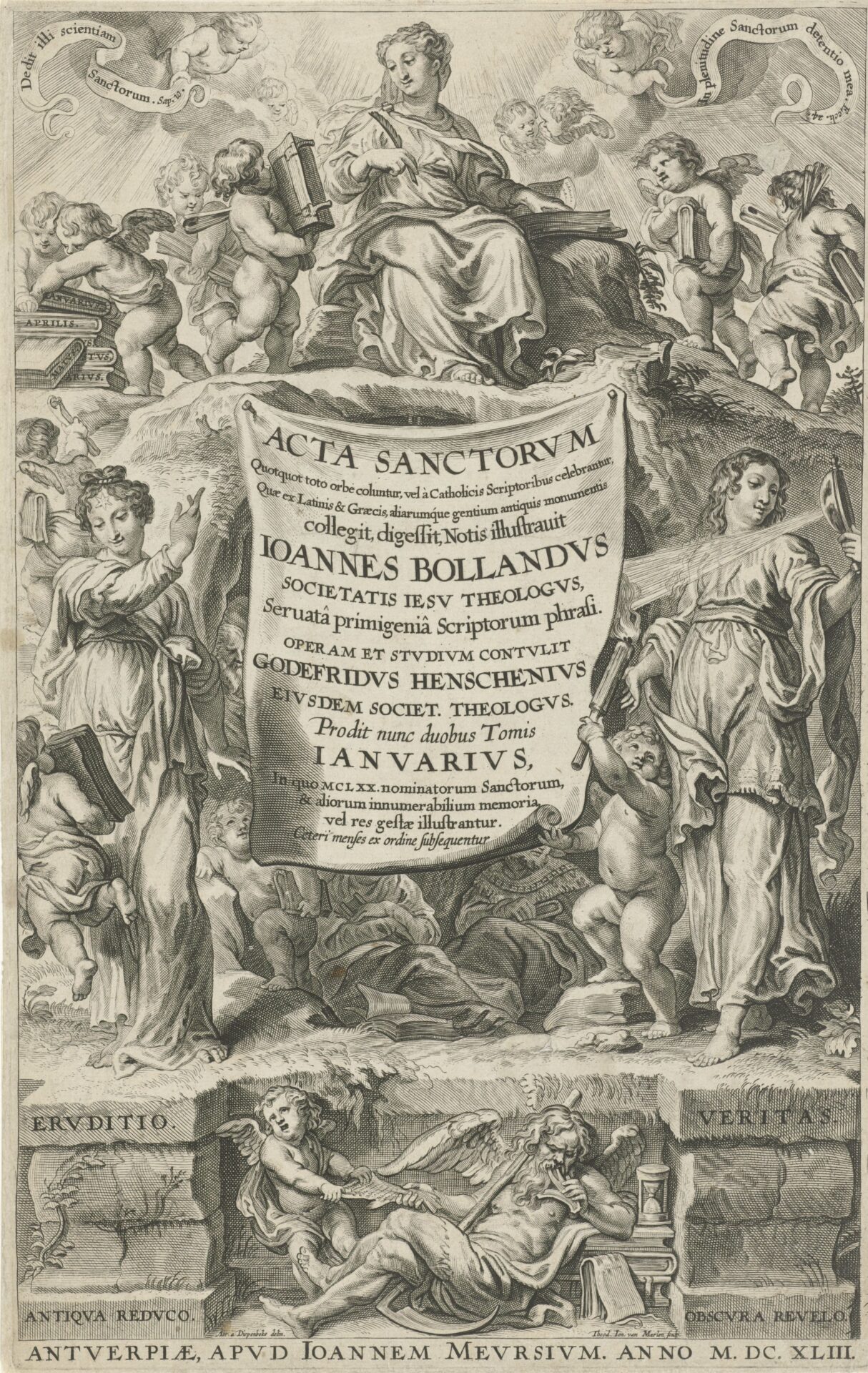

At the Royal Library of Belgium (KBR), UNESCO formally presented its Memory of the World certificate to the Acta Sanctorum, the vast, centuries-long scholarly endeavour produced by the Society of Bollandists – only the eighth such recognition ever awarded to Belgium.

At first glance, the honour seems improbable. The Acta Sanctorum is not a blockbuster archive or a symbol of state power, but a 67-volume, 60,000-page critical encyclopaedia of saints’ lives, compiled painstakingly between the 17th and 20th centuries.

Its authors were Jesuit scholars who specialised in scepticism, source-checking and historical precision – an unusual combination in the business of saints.

Yet that unlikely pairing is precisely what UNESCO sought to recognise. Founded in Antwerp in the early 1600s by Jean Bolland and his fellow Jesuits, the Bollandists pioneered a method that applied rigorous historical criticism to religious texts. In doing so, they effectively invented a new discipline: critical hagiography. Saints were no longer simply venerated; they were investigated.

Few people know about Bollandists, the religious group behind the world’s most authoritative collection of works on saints.

Behind the printed volumes lies an even more remarkable archive. Over generations, the Bollandists assembled nearly 300 volumes of correspondence, manuscript copies and research notes, drawing on a pan-European network of scholars.

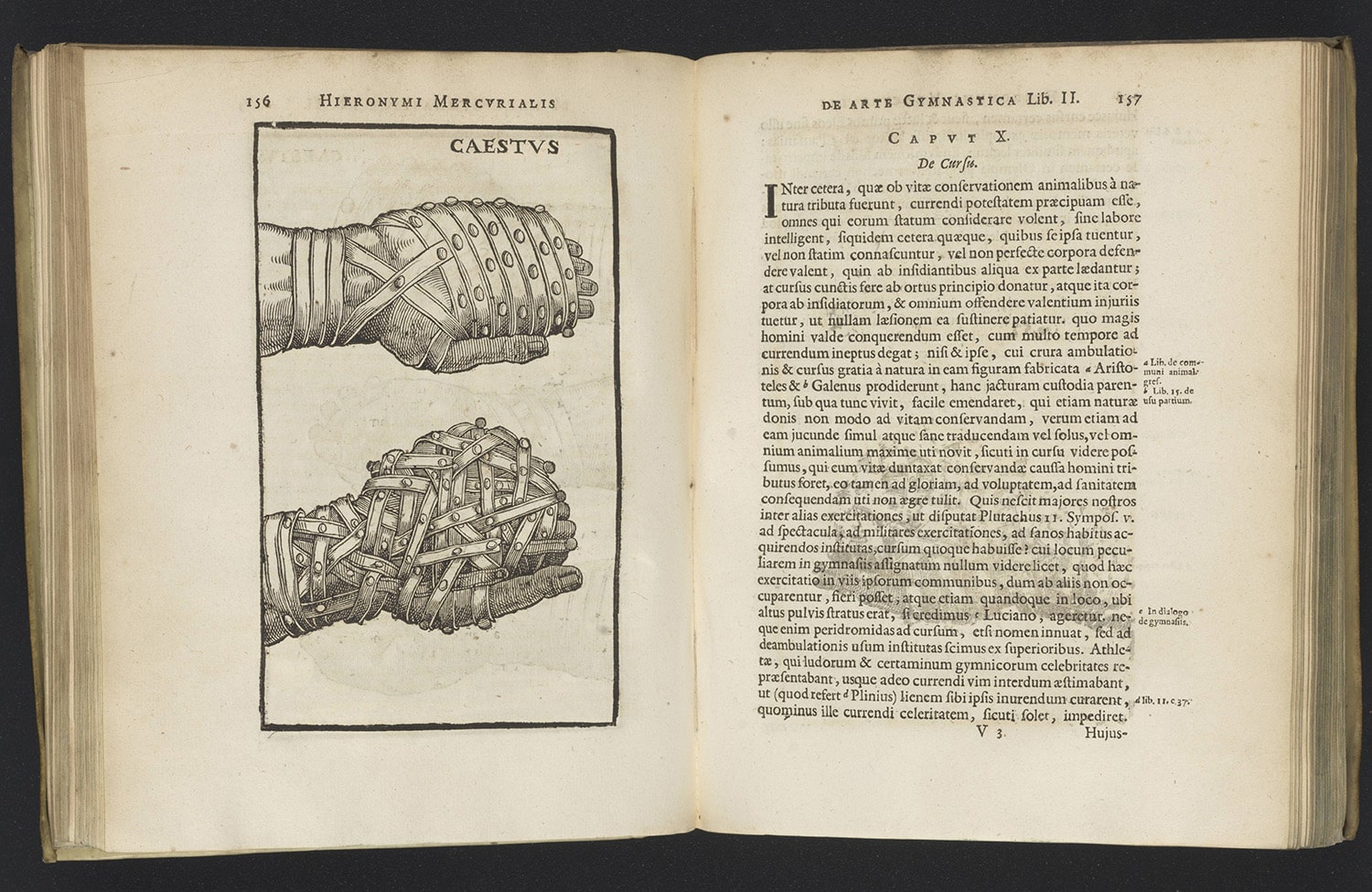

Many of the medieval sources they transcribed have since vanished, leaving the Bollandist archives – now shared between their Brussels library in Etterbeek and KBR – as the sole witnesses. More than 700 engraved copper plates, once used to print illustrations, survive alongside letters, diaries and documents that chart early modern Europe’s intellectual networks.

That such an inward-looking institution should now attract global attention is a relatively recent development. In 2024, Pope Francis made an unprecedented visit to the Bollandists’ Brussels centre – the first papal visit in the society’s 400-year history – blessing a collection long better known to specialists than to the wider public.

The Bollandist archives are now shared between their Brussels library in Etterbeek and KBR.

UNESCO’s recognition places the Bollandists in distinguished company, alongside Belgium’s Solvay conference archives and the Mundaneum’s Universal Bibliographic Repertoire. It also serves as a reminder that intellectual ambition does not always announce itself loudly.

And their methods have changed. Speaking at the award event, Robert Godding, director of the Bollandist Society, said that when Jean Bolland started his work, the thousands of mainly Greek texts on the saints composed over the centuries, “were an unknown continent since most of them were still preserved only in manuscript form.”

Now, he noted, “Bollandists now make use of all the resources of radiography, chronology, linguistics, geography, topography, and many other disciplines.”