Robert Cailliau does not look like a man who helped change the world. At home in Prévessin, the unassuming French commune just across the border from Geneva, he is genial, amused, slightly self-effacing.

CERN, the intergovernmental particle physics laboratory where he once worked, lies only minutes away, a familiar presence rather than a monument. In his office is the box of a gigantic Lego Eiffel Tower, still unbuilt, a birthday present from former colleagues. Somewhere nearby is a smaller model he has already assembled. He speaks with pleasure about tolerances in the ABS plastic used for the Lego bricks, about precision engineering measured in thousandths of a millimetre. It is the language of a man who still delights in how things fit together.

It is also, in its way, the language of the World Wide Web.

Cailliau is one of the web’s unsung architects: a Belgian engineer who worked alongside Tim Berners-Lee at CERN as the web quietly took shape in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Berners-Lee wrote the original code, sketched the protocols, and became the public face of the invention. Cailliau did something no less essential. He believed in the project early, defended it internally, found people and resources for it, evangelised it to the wider world, organised the first global gatherings of web pioneers–and crucially, pushed CERN to give the web away, royalty-free, to everyone.

Without that decision, and without Cailliau’s patient persistence inside a large, sceptical research institution, the web as we know it might never have escaped the confines of a physics laboratory on the Franco‑Swiss border.

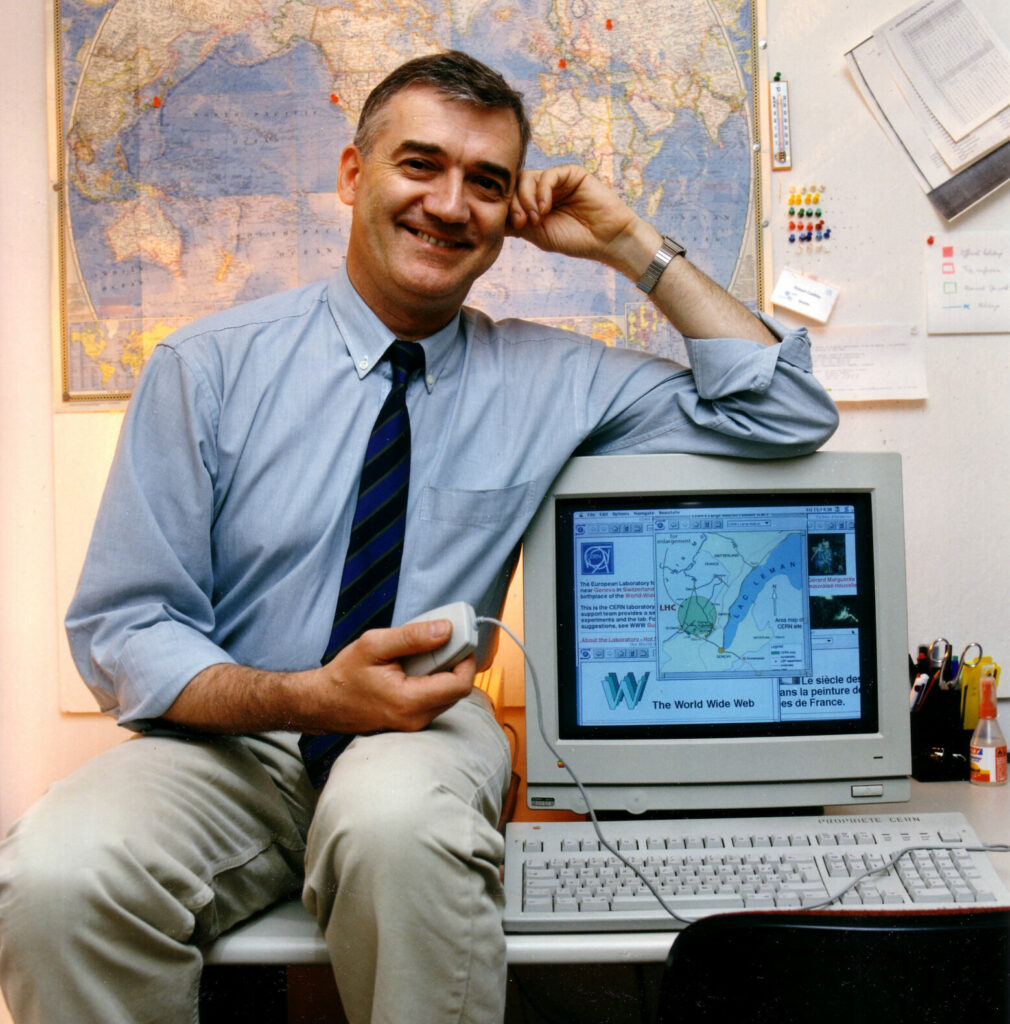

World Wide Web inventor Robert Cailliau poses for a portrait picture, Wednesday 08 November 2006, in Tongeren, prior to being honoured by the Vermeylenfonds. Credit: Belga

Robert Cailliau was born in 1947 in Tongeren, Belgium’s oldest city, a place steeped in Roman layers and quiet continuity. It is a fitting origin for a man whose most consequential work would be about connection rather than disruption. His childhood, he recalls, was shaped less by ambition than by curiosity. In his office, he rummages around to locate a remnant of his Belgian background: a model of Tintin’s Moon rocket. He was eight years old when the iconic Explorers on the Moon comic album was released. “I was waiting for it,” he says. “It was so far ahead of its time. It was so well researched, it was just amazing.” He’s also proud to live not so far from the Hotel Cornavin in Geneva, which appears in another of the Tintin books, The Calculus Affair.

His family later moved to Antwerp, where the bustle of a port city contrasted with the measured rhythms of provincial Limburg. He went on to study engineering at Ghent University, graduating in 1969 as a civil, mechanical and electrical engineer–a broad formation that still defines his thinking. Belgian engineering education, he likes to note, emphasised pragmatism over showmanship. You learned to make things work, to respect constraints, to accept compromise. “Engineering,” he says, “is not about elegance on paper. It’s about systems that behave properly in the real world.”

That sensibility would matter later. He developed a particular fascination with control systems: the automatic mechanisms that allow complex machines to respond quickly and safely. “In all these things,” he says, “it’s very important to have automatic systems that can react in very fast time. You very quickly run into non‑linear systems, which are mathematically interesting–but also very demanding.”

CERN in Switzerland

To deepen that interest, he crossed the Atlantic to the University of Michigan, completing an MSc in computer, information and control engineering in 1972. Computing, at that point, was not yet glamorous. It was a tool–necessary, sometimes awkward, increasingly unavoidable. During his military service in the Belgian army, Cailliau maintained Fortran programs simulating troop movements. It was not exactly the stuff of digital dreams, but it taught him something important: computers were already creeping into every domain, often unnoticed.

CERN: a European crossroads

When he joined CERN in 1974 as a Fellow in the Proton Synchrotron division, Cailliau entered one of the most extraordinary scientific environments on earth. CERN, straddling the Swiss–French border, was–and remains–less a single institution than a meeting place. Physicists from dozens of countries arrive, collaborate, argue, experiment, then return to universities scattered across the globe. Knowledge moves constantly; documentation, less so.

The laboratory itself sits astride the Swiss and French borders. Had CERN not been international, Cailliau likes to joke, he and Berners-Lee would have needed to show their passports every time they walked between offices. That daily crossing of boundaries, both literal and intellectual, mattered. It created a culture in which heterogeneity was normal and interoperability essential.

By the late 1980s, Cailliau was leading CERN’s Office Computing Systems group. Personal computers were appearing on desks. Networks snaked through corridors. And yet, the daily reality of information‑sharing remained painfully analogue.

“People would finish a document, put it on a diskette – remember those? - and send it through the internal mail,” he recalls. “CERN is very big. The mail would be delivered twice a day. So you’d often wait until the next day to receive something that already existed electronically.”

It was an engineer’s irritation: the sense that all the pieces were there but badly assembled. Networks existed. Printers existed. Computers existed. Why, then, couldn’t a document simply move from computer A to computer B?

That is essentially how it began. The World Wide Web was not born with a bang. It emerged, almost apologetically, from corridors, cafeterias and coffee breaks. Its early days were marked less by grand vision than by everyday annoyance: a document that took too long to arrive, a system that did not quite talk to another. Revolutions sometimes begin not with manifestos but with the quiet conviction that something ought to work better than it does.

There were partial solutions: early network tools, file transfer systems–but nothing that felt natural, intuitive, or universal. Cailliau began thinking seriously about hypertext: the idea that documents could be linked electronically, allowing readers to jump between them. In 1988, he wrote a short internal proposal suggesting that CERN explore hypertext over networks.

Robert Cailliau

It was a modest document: just a page long, printed on yellow paper. For years, Cailliau kept track of it, occasionally rediscovering it, promising himself he would file it properly. Then, inevitably, he lost it again. “One day,” he says, smiling, “it will probably turn up and go to a museum. For now, it’s still missing.”

At almost exactly the same time, a CERN physicist was thinking along similar lines: Tim Berners‑Lee, who was working in a different division, had grown frustrated with the labyrinth of incompatible systems used to store and access CERN’s documentation. In March 1989, he wrote a proposal for a networked hypertext system to solve the problem.

Cailliau is characteristically modest about that moment. “From the engineering point of view, there was not really a design. It was sort of a, ‘Let's try this, if not, let's try something else,’” he says. “And we took something that existed already, modified it a little bit to make it work. So is that an invention?”

But he does praise Berners‑Lee for his out-of-the-box thinking. “The thing that nobody had thought of before, for which there was no prior art, was the URL: the putting together in a single string of characters, the protocol. http colon, double slash. I asked him, ‘Why are there two slashes?’ He said, ‘Well, actually, we don't need them.’

“So you have the protocol, the service name, and then – and this is the genius of it – the rest of what you type after that, which is interpreted exclusively by the server you send it to. So wherever you want to go to, right? Www, dot, Brusselstimes, dot, com. In the beginning, that third part was just a path through the folders to a file in the file system. But quite quickly other uses were found.”

Selling it

One of the CERN managers at the time, Mike Sendall, famously described the proposal as “vague but exciting.” What is less well known is what happened next. Sendall passed the document to Cailliau and asked him for a second opinion. Cailliau was already working on hypertext ideas. He immediately saw the potential.

“I wasn’t happy with the people who wanted to centralise everything on a single mainframe,” Cailliau recalls. “I knew that wasn’t what people wanted.”

The two men teamed up. Berners‑Lee focused on the technical architecture: HTTP, HTML, URLs, and the first browser and server. Cailliau became the project’s internal champion. He co‑authored proposals, lobbied management for time and resources, recruited students, and tried–often against considerable resistance–to persuade CERN that this odd little project was worth backing.

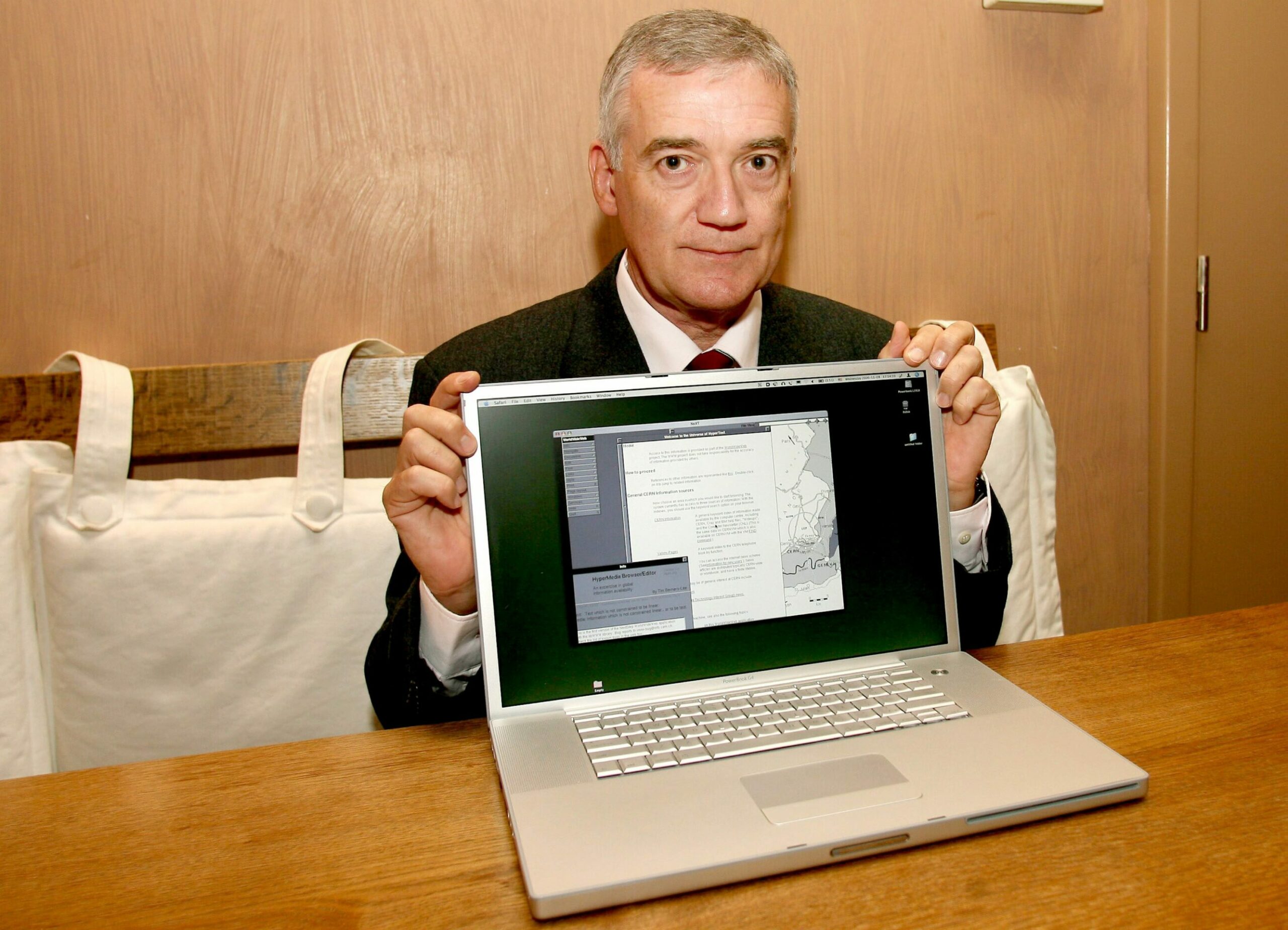

L-R: Robert Cailliau, Tim Berners-Lee, and Nicola Pellow, internet pioneers at the birth of the WWW

CERN, after all, was a physics laboratory. Computing projects were tolerated only insofar as they served particle physics. Manpower was scarce. Budgets were tight. Convincing senior management to allocate staff to an unproven information system required not brilliance, but persistence.

Cailliau provided exactly that. He found students who would later become key figures in web history. He organised demonstrations. He explained, re‑explained, and explained again. He became, in effect, the web’s first European civil servant.

Coffee and coincidence

Why did the web emerge at CERN, rather than in Silicon Valley or a corporate research lab? Cailliau’s answer is disarmingly simple.

“CERN is essentially a service organisation,” he says. “Very few physicists are actually on CERN’s payroll. Most come from universities all over the world.”

That diversity created constant friction–and creativity. It also created an acute need for a system that allowed people to consult documents without knowing where they were stored, which machine they lived on, or which operating system they required.

Then there was the cafeteria. “That’s the most important place in any CERN building,” Cailliau insists. “When inspiration dries up, you go and have a coffee. We convert coffee into ideas.” Sometimes those ideas were refined over a beer on the terrace. It was on one such evening that Berners‑Lee suggested a name.

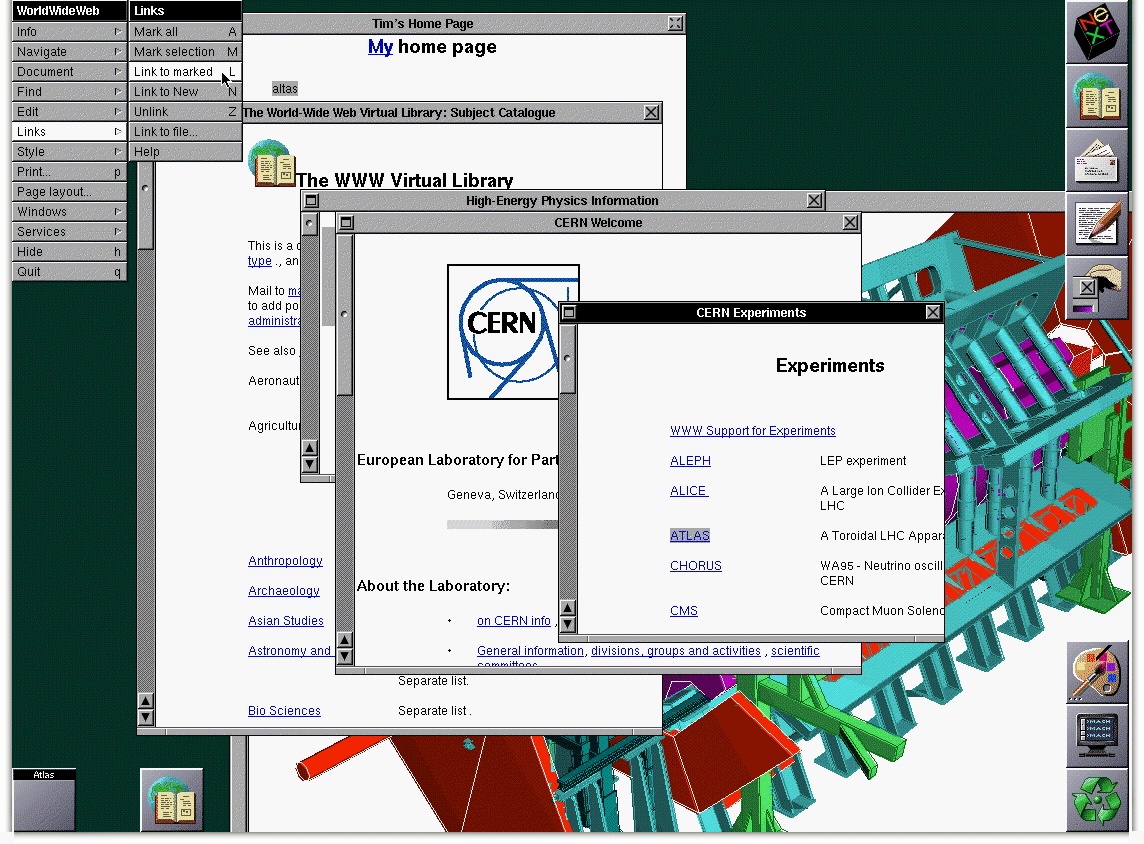

Screen shot of a NeXT computer running Tim Berners-Lee's original

WorldWideWeb browser; and the browser in 1993

Cailliau had been determined not to borrow yet another term from Greek mythology. Berners‑Lee proposed ‘World Wide Web’. “I liked it very much,” Cailliau recalls, “except that it is difficult to pronounce in French.”

The name stuck. So did Cailliau’s green three interlinked Ws, which reflected his synaesthetic habit of seeing letters in colour. “The type font should be Hermann Zapf's Optima,” he says. “Its letters do not have serifs, but there is a slight hint of a serif in the somewhat curved ends of the strokes. The ends are never straight lines.” When he organised the conference, he even had pins of the logo made for each participant. The web, still embryonic, had an identity.

Letting it go

What the web did not yet have was institutional security. For much of its early life, it survived hand‑to‑mouth. Cailliau organised student projects to build browsers for different systems, including the Macintosh. He organised the first International World Wide Web Conference at CERN in 1994, a gathering so oversubscribed it became known as the “Woodstock of the Web.”

And he pursued what may have been the most consequential bureaucratic task of all: persuading CERN to release the web’s core technology into the public domain.

That decision, signed on April 30, 1993, took months of negotiations with CERN’s legal service and repeated arguments at the directorate level. It was not inevitable. CERN could have patented the technology or licensed it selectively. Instead, under pressure from Cailliau and Berners‑Lee, it gave it away. “That was hugely important,” Cailliau says, drawing a deep breath.

First logo designed by Robert Cailliau

It was also deeply European in spirit: public research, publicly funded, released for the common good. In an era before “digital sovereignty” entered the Brussels lexicon, it embodied a set of values that now feel almost quaint.

Cailliau himself organised the first International Conference on the World-Wide Web, known as WWW1, in Geneva in May 1994. He was president of the committee, but got out of it in 2002. He recognises that his active role in shaping the web was over more than two decades ago.

Outgrowing its creators

Meanwhile, the web’s growth quickly exceeded anything its creators had imagined. In 1991, there were a handful of servers. By 1993, there were hundreds. By the mid‑1990s, thousands were being added every month. Mosaic, the browser developed at the University of Illinois’ NCSA, made the web accessible to non‑specialists. Commercial interest exploded.

“At some point,” Cailliau says, “it escaped.”

CERN, focused on building the Large Hadron Collider, could no longer justify deep involvement in an informatics project. Web development moved to the newly created World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), based at MIT, INRIA and elsewhere. Berners‑Lee left CERN. Soon after, Cailliau ceased work on web matters, devoting his time to public communication, conferences, and education.

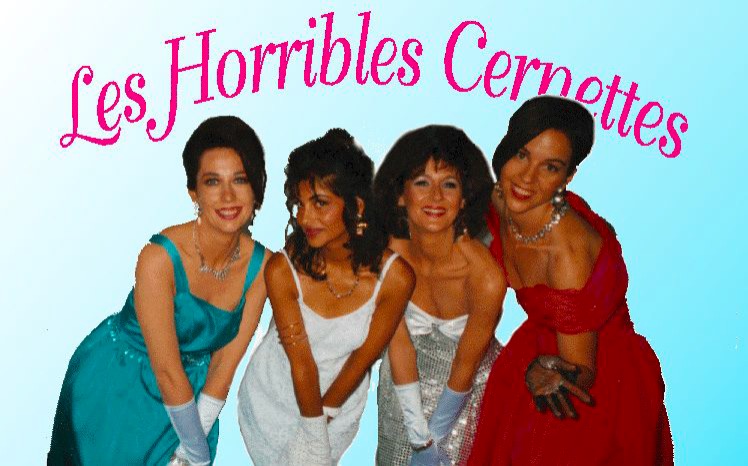

The first picture published on the World Wide Web was uploaded in 1992.

There was pride, certainly. But there was also a growing unease. “The web people imagine today is a set of independent servers linking to each other. That web hardly exists anymore,” Cailliau says. “What we have now are giant platforms. You don’t navigate by following links. You ask a search engine.”

Wikipedia, he believes, is one of the few survivors of the original spirit: a place where one page naturally leads to another, curiosity rewarded rather than monetised. “That same web exists in Wikipedia, but all the documents are inside the same server, if you like. You run around,” he says.

Even AI, which some people compare in technological terms to the CERN innovations, is still building on the breakthrough of the 1980s and 90s, Cailliau says. “The architecture hasn't changed. The AI uses big servers that you connect to, and you hang around in there, and then that's it.”

Big tech, broken promises

Like so many technologies, the web had its downsides, which are all too familiar today: misinformation, disinformation, online toxicity, surveillance, the erosion of privacy, distraction cultures, Big Tech behemoths. But none of these were on the horizon when the web’s early architects were mulling hyperlink protocols in the CERN cafeteria. And Cailliau is careful not to frame the internet’s current problems as simple betrayals. “There was no design,” he laughs. “So there were no design flaws.”

The internet and the web were built for academia, a world where spam, disinformation and mass surveillance were not part of the culture. “That just wasn't done. That's not in the ethos of any of us. It was designed for fast communication between academia,” he says.

Those pathologies emerged later, once the network became public and commercial. What happened after could not have been anticipated. “Couldn't prevent, didn't foresee, couldn't have foreseen.”

What troubles him most is centralisation. “We are back to the mainframe model,” he says. “People don’t store their data locally anymore. They leave it on servers run by companies they don’t control.”

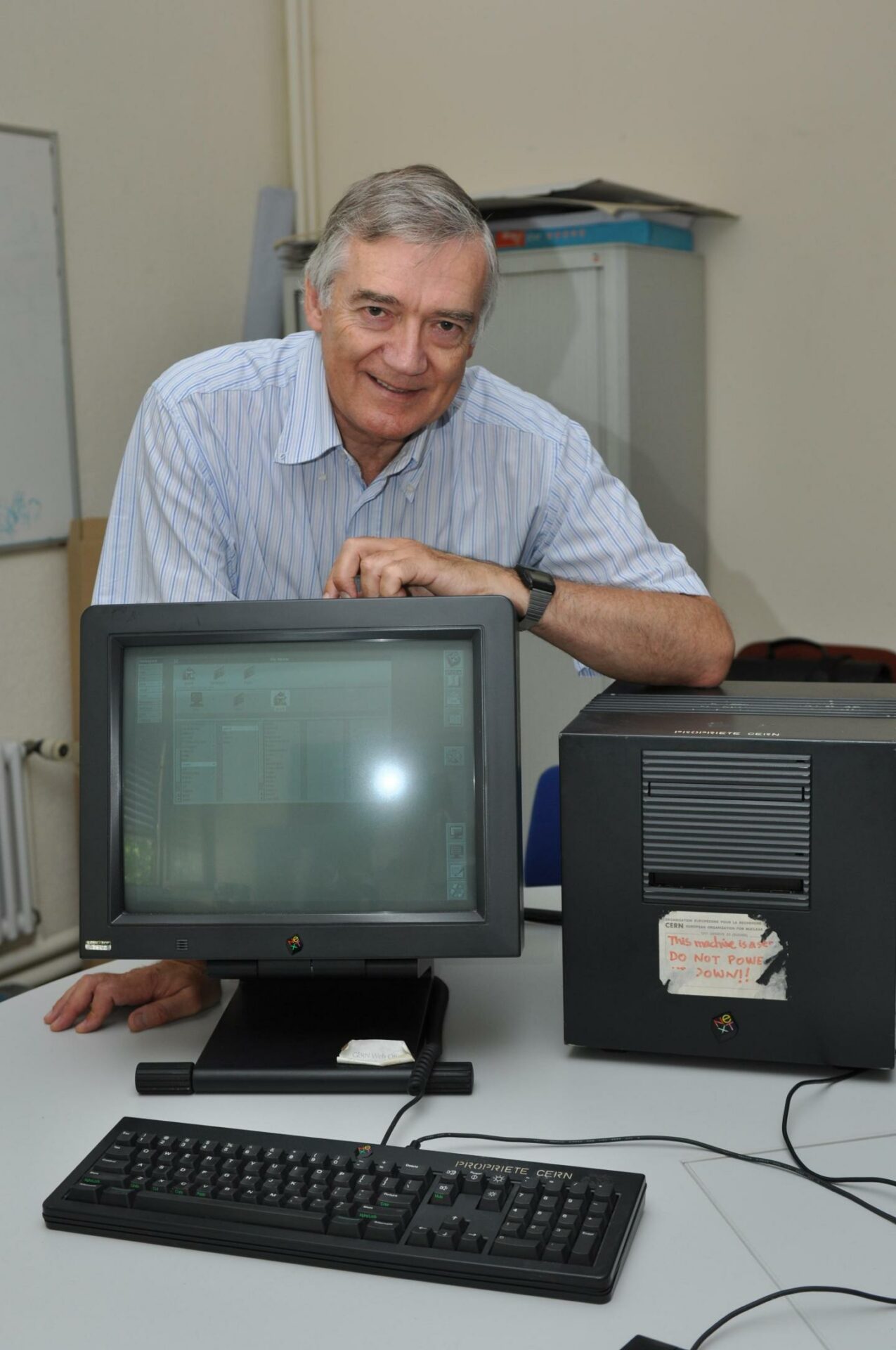

Robert Cailliau seen with the world's first web server

He avoids social media almost entirely. “I must have a Facebook account from very, very, very early on, just to try these things out. And I was offered a LinkedIn account by the founder of LinkedIn, and I said, ‘No, thank you,’” he says. He has, reluctantly, been forced onto WhatsApp by his children. Otherwise, he prefers distance. “They suck in your soul,” he once said. He has not changed his mind.

Europe’s attempts to regulate big tech, through instruments like the GDPR and the Digital Services Act, strike him as necessary but incomplete. Regulation is essential, he believes, but it arrived late and struggles to keep pace with companies that operate across borders and legal systems.

“What worries me,” he says, “is not what governments might do, but what commercial companies do in the vacuum that governments leave.”

A life after invention

Today, Cailliau is officially retired, but hardly inactive. He remains an external collaborator at CERN’s IdeaSquare, working on education, innovation and the transmission of knowledge to younger generations. It is a role that suits him.

“What matters to me now,” he says, “is not building new systems, but helping people understand the ones we already have.”

Prévessin is a place of quiet routines rather than grand statements. It mirrors something of Cailliau’s own disposition. He has received honours – academic prizes, decorations, a Belgian knighthood, honorary citizenship in Tongeren – but none of that seems to weigh heavily.

The Lego Eiffel Tower will eventually be built. The lost yellow paper may yet resurface. The web, meanwhile, continues to evolve in ways both exhilarating and unsettling.

Asked how he feels about his role in all this, Cailliau pauses. He does not claim ownership. He expresses no regret.

“I don’t feel guilty,” he says. “We couldn’t have foreseen it. I feel proud of having been involved. But what the web became–that’s something no individual could ever control.”

It is a modest answer. And perhaps that, more than anything, explains why one of the quiet Europeans behind the web still does not quite get his due.