Peter Townsend was the Air Force ace who might have married Britain’s Princess Margaret, but his romance rocked the Palace. He was shuffled out of Britain but, as Dennis Abbott writes, he eventually found a new life in Brussels

Who was Peter Townsend? In the 1950s, everyone knew. He was the dashing Battle of Britain flying ace supposed to marry Princess Margaret, sister of Queen Elizabeth II.

However, there was no fairytale wedding for the RAF Group Captain. Fearing a royal crisis, the out-of-touch English establishment shot down his romance with Margaret, posting him to Brussels.

The saga made Townsend a household name and – thanks to the global success of the Netflix series, The Crown – his tale has captured the imagination of a new generation today. What is far less well-known is that exiled Townsend would discover the true love of his life in Belgium, as well as a thirst for new adventures.

War stories

Peter Townsend’s story began on the other side of the world. He was born on 22 November 1914 in Rangoon, Burma, the fifth of seven children, son of one of a handful of Crown representatives ruling 15 million Burmese.

As a boy, Townsend was passionate about flying, joining RAF Training College Cranwell aged just 19, and making his first solo flight after just six hours’ training. He was commissioned as a pilot officer in 1935, and a year later, led a squadron that flew to India’s northwest frontier, a five-day journey of 7,000km.

When war broke out, he proved himself an effective fighter pilot and squadron leader: he was credited as the first pilot to bring down an enemy aircraft on English soil in February 1940. Though he was twice shot down in dogfights, his final tally was impressive: nine enemy aircraft destroyed, two shared kills, and four damaged.

By 1944, he was promoted, married and a father to two sons. He was also Air Equerry to King George VI. On his first day, he was also introduced to the King’s daughters, Elizabeth, then 17, and her 13-year-old sister Margaret. Townsend quickly made himself a trusted member of the Royal Household, living in a cottage close to Windsor Castle. His second son, Hugo, born in June 1945, could boast the King was his godfather.

Townsend (right) with King George VI at a rally in Hyde Park, 1951.

He was promoted again, becoming Assistant Master of the Household, then Group Captain. He also divorced his wife in 1952.

Meanwhile, Townsend’s duties now involved more contact with Margaret, and they confided their feelings to each other. The Princess then told her sister and mother, while Townsend informed the Queen’s secretary, Sir Alan Lascelles. “You must be either mad or bad,” said Lascelles in disbelief. The Queen was sympathetic but, as head of the Church of England, Lascelles said she could not consent to Margaret marrying a divorced man. However, if the Princess could wait until she was 25, she would no longer require her sister’s approval.

But when the stories emerged in the press, just days after Elizabeth’s coronation in 1953, the Palace panicked. The old guard was fearful that a marriage between the Queen’s fun-loving sister and the divorced war hero would damage a monarchy still recovering from Edward VIII’s abdication for the twice-wed American Wallis Simpson.

Princess Margaret in Jamaica, in 1955.

Townsend had to be posted abroad immediately. Lascelles gave him a choice of three postings: Singapore, Johannesburg or Brussels. The latter was the obvious one as he would stay close to his sons – and see Margaret “under the radar”.

Exile

Townsend’s appointment as Air Attaché was arranged so quickly that the British Ambassador to Belgium, Sir Christopher Warner, knew nothing about the decision until he read it in a newspaper.

As for Townsend, any thoughts of a quiet life in Brussels were quickly dispelled. Twenty police officers instead of the usual two were on duty outside the British Embassy in Rue de Spa when he arrived for his first day. The Embassy issued a communiqué stating that “Group Captain Townsend will be staying for some days from his arrival as the guest of the British Chargé d'Affaires, Mr. C.C. Parrott (69 Avenue Churchill).” How journalists today would enjoy such transparency.

Townsend initially sought a low profile. He settled into a furnished ground-floor flat in the fashionable Square du Bois, off Avenue Louise (known colloquially today as the Square des Milliardaires). He wrote to Margaret almost daily. He did, however, attend a ball hosted by the Ambassador soon after his arrival, but declined invitations to dance. Belgian Prime Minister Jean Van Houte’s daughter Marie Louise commented: “We had been saying: ‘If Group Captain Townsend does not dance, he must be in love’, and, voila, he does not dance.”

Around this time, Townsend attended a horse show in Brussels. A young Belgian competitor, Marie-Luce Jamagne, caught his eye. Suddenly, her horse fell and she was thrown to the ground unconscious. Townsend immediately leapt up to help and was later introduced to her parents.

Townsend also tried his hand at show-jumping and racing, including at the Hippodrome de Groenendael. He would rise at dawn every morning, driving through the Forêt de Soignes to the Groenendael gallops. His riding rapidly improved and he was soon competing all over Europe – from Deauville to Copenhagen.

Media pressure

In October 1955, Townsend and Margaret reunited in London, but while the popular press backed the marriage, the establishment and the Church remained opposed. It was time to end the uncertainty. He drafted a statement for Margaret. “Our feelings for each other were unchanged, but they had incurred for us a burden so great that we decided, together, to lay it down,” he recalled.

Townsend quietly left London and returned to Brussels. Seeing his apartment surrounded by reporters, he took up an offer from the new Ambassador, Sir George Labouchere, to stay at his Rue Ducale residence.

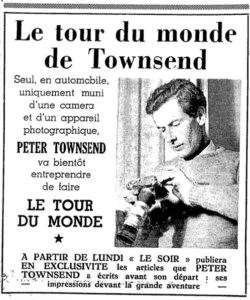

Townsend had been promised a new command in the RAF but was increasingly thinking of a fresh start. That same week, he retired from the RAF after 23 years’ service. He also decided to make a solo journey around the world and write a book.

Before leaving Brussels, Townsend agreed to write a series of columns for Belgian newspaper Le Soir, recounting his experiences during his 90,000km journey. He set off on October 21, leaving Brussels in dense fog, “bent on escaping into the unknown world which lay beyond the confines of conventional society.”

Townsend then tracked back to Peru, where he was photographed with Gladys Zender, the 17-year-old Miss Universe. The pictures sparked rumours of a romance, but Townsend was quickly back on the road, driving through the desert to Chile. He then journeyed through the Belgian Congo, meeting Nobel Peace Prize-winning doctor Albert Schweitzer at his hospital in French Equatorial Africa. He eventually arrived back in Brussels at 1.30am on March 24, 1958, at the wheel of the same vehicle in which he set off 17 months earlier.

Marriage to Marie-Luce

Back in Belgium, he found consolation in the company of Marie-Luce, who had matured “into a delightful girl, now 19, tall and alluring”. Success as a showjumper had not changed her “straight, generous, and pleasingly witty” personality.

While attending the Expo 58 exhibition in Brussels, they were introduced to some Americans who mooted that Townsend could make another world tour, this time by air, and film at the locations he had visited previously. Townsend leapt at the idea of a documentary. The film team was led by director Victor Stoloff and included Marie-Luce as official photographer, The documentary, ‘Passeport pour le Monde’ was released in May 1959 and Townsend’s accompanying book, ‘Earth, My Friend’, came out the following month.

By now, Townsend and Marie-Luce were inseparable, despite her fears of being a “second best” to Margaret. Townsend, at 42, was also more than twice her age. Marie-Luce accepted his marriage proposal. Townsend informed Margaret, who had recently formed an attachment with the society photographer Anthony Armstrong-Jones. She later explained, “I received a letter from Peter in the morning and that evening I decided to marry Tony. It was no coincidence.”

Townsend and Marie-Luce were married by Mayor Jacques Wiener in Watermael-Boitsfort on December 21, 1959. After honeymooning in Switzerland, they lived in an apartment on the Quai Louis Blériot in Paris, a fitting choice for the former airman, before moving to a maison bourgeoise in Sainte-Gemme, a village 18 miles west of the capital. He and Marie-Luce also started a family. Isabelle was born in June 1961, followed by Marie-Françoise in July 1963.

Writing

Not long after, Townsend took up an offer from a New York wine-shipping firm to set up a subsidiary in France. The fact he knew next to nothing about wine didn’t put them off.

Townsend’s writing also attracted attention. He was approached by Paris-Match to write an article on the Battle of Britain. It immediately triggered offers from three publishers for a book. The research for ‘Duel of Eagles’ took him to Germany, where he was reunited with Karl Missy, whose plane he shot down in 1940.

Townsend was also brought in to help promote ‘Battle of Britain’, a movie made by James Bond director, Guy Hamilton. Townsend was a guest of honour at the film’s premiere at the Marivaux cinema in Brussels on September 24, 1969, which was attended by Prince Albert, Belgium’s future king.

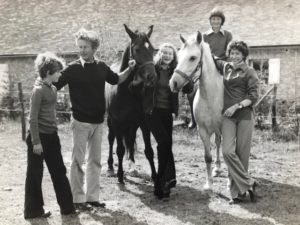

Townsend with family in Saint-Léger-en Yvelines, in the mid-70s.

By the early 70s, Townsend had become an established author and special correspondent for Paris-Match. In October 1973, he was asked to report on the Yom Kippur War. His 1976 book, ‘The Last Emperor’, was on a subject he knew more about than most: King George VI. His autobiography, ‘Time and Chance’, came out in 1978 and his later books included ‘The Postman of Nagasaki’ and ‘Duel in the Dark’.

In summer 1992 Townsend travelled to London for a reunion of Palace courtiers. Margaret invited her former suitor to Kensington Palace. She reportedly commented that Townsend was as charming as ever and hadn’t changed, except for his grey hair. It was the last time they saw each other. On her instructions, the letters they exchanged during their romance will not be released until 2030.

Final tribute

Townsend died, aged 80, on June 19, 1995. The funeral took place in Saint-Léger-en-Yvelines, his French home since 1968. Princess Margaret died on February 9, 2002, aged 71. Townsend’s former wife Rosemary passed away on February 27, 2004, aged 82. His eldest son Giles, a wine merchant, died on July 7, 2015, aged 73.

Marie-Luce and his other children are all still alive. Hugo became a Catholic monk before leaving holy orders to become a psychotherapist. He is married to Belgium-born Princess Yolande de Ligne and lives in London. Isabelle is an actress and former fashion model, living near Paris with her husband, estate manager Patrick Deedes-Vincke. Marie-Françoise works for an interior designer in Paris. Pierre has spent his career in the humanitarian sector.

However, Townsend’s story still resonates today. In ‘The Crown’, his romance with Margaret is one of the enduring subplots. And this July, when his 11 medals were put up at an auction – including the DSO (Distinguished Service Order), DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) and CVO (Commander of the Royal Victorian Order) – they sold for £260,000.