In its 16th-century pomp, Antwerp was at the hub of the known world. It was a cauldron of emperors, heretics, spies and killer bankers, all stirring religious, sexual and intellectual scandals. Michael Pye, author of ‘Antwerp: The Glory Years’, recounts what it was like to live in a city that oozed power and plots

There are rules about any expedition to find lost cities and their riches. You need a legend, a jungle, a river, a dugout canoe and a guide and a machete, an ancient, tattered map, anti-malarials and something to keep off jaguars, piranhas and anacondas. There may be traps, an enemy or something more deadly and uncanny.

Or, if you don’t have the time, you could always take the train to Antwerp.

Among the frocks and beers and chocolate, there are the remains of another lost city. In the 16th century, Antwerp was the hub and centre of the known world, and the city’s great rivals like Venice said so when they reported home.

The world waited for every bit of news: the market in money or gold, the rumours of peace or better yet, scandal. Killer bankers, money being cornered like any other commodity on the Exchange, women who laughed at dirty jokes in front of their own husbands. You could go from dinner table to dinner table round Europe with a stock of Antwerp stories.

That city is long gone, hidden behind the 17th century story, which is Rubens and pious Catholicism and respect for Hapsburg rulers. True, the city itself is still a great port as it was in the 16th century when it connected the new trade routes over oceans with the northern seas that were easier to enter and escape than the Mediterranean, and the great rivers that carried goods into Europe much more efficiently than ruined roads.

It isn’t buried or overgrown like lost cities are meant to be. Although rockets rained down on it in World War II, it was the first civilian target in Europe bombed in the First World War and it had town planners in the 19th century. The line of the streets in the old centre is still much as it was, although you buy Louis Vuitton on the Meir instead of cabbages.

The lost city of secrets and spices

Today, you must hunt for clues to the 50-years when Antwerp was a new kind of world city: no empire, not even an army or a navy, no king or royal court, no convincingly important lord and not even a bishop.

What it had was a market in secrets and spices, diamonds and pictures, wool, copper bangles, and tombs that looked royal. It also had books, ranging from Bibles in many languages to the new medical ideas coming over the oceans, with roots and leaves from Asia, America and Africa.

The city was a crossroads of every kind of information, where spies went to find out what they couldn’t find anywhere else. People buying guns and armour meant war. Even more important was what kind of money they were raising to pay troops: the coins they wanted would show where they meant to find soldiers and where they would fight.

The city was always being read as closely as any set of documents. The king of the Exchange kept 20 thugs to keep him safe but also to watch the streets to see who was going where to make deals with whom. You could even buy a very early kind of Financial Times: lists of the exchange rates and commodity prices issued each day and for sale around the city’s true heart: its Beurs, its Exchange.

On the top floors of the Beurs: the market in art

Antwerp was about business, and its business was about discovering the world. The grandest of thinkers and scholars – Roger Ascham for example – said they felt at home with Antwerp merchants.

The merchants among themselves grumbled about how business got in the way of the next edition of some Latin poet or the great history they were planning. But somehow the books still appeared. The docksides were full of strange new goods with strange new uses, enough for the great doctor Paracelsus to say he learned more from Antwerp’s markets than from any school.

The world’s first modern cosmopolis

The world connected in Antwerp. It was a buzz of excitement that changed the way we think about money for example: in a town of deals, money quickly becomes an abstraction.

Many varied groups did deals there: the ‘new Christians’ from Portugal, who were often still practising Jews; the Lutherans from Germany; the Calvinists who became less and less discreet until they made a Calvinist Republic of the town; assorted Anabaptists; and even the secretive Family of Love.

The hedge–preachers, the Calvinist teachers.

Officials of the Hapsburg empire complained it was somehow unfair to have so many varieties of heretic. Charles V, the Hapsburg emperor, kept saying he wanted to stamp out heresy, but he also needed money. Antwerp was a place to raise cash quite cheaply. That was the very delicate balance on which the city’s kind of unacknowledged independence rested. The city ran around the Emperor’s will, got sick or got up late to give the heretics time to get away, printed Bibles in English which were still illegal in England but burned them in the streets the next year.

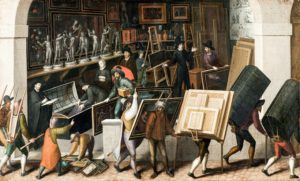

It was an elaborate, knife-edge game that kept the wars of the Reformation out of the streets the night when a handful of men rushed into the churches and smashed up images and pictures. An attack on the Church’s authority was an attack on the Emperor’s authority – or so the Emperor thought.

So the armies had to come into the streets. A fortress was built with its first guns pointed at the city – not the river – which might bring an enemy. The greatness of Antwerp began to drift and then to run North. In 1585, after a long siege, Antwerp was back in the hands of the Spanish, Protestants were allowed to leave and they did, and the city began to have lovely baroque churches, a dearth of heretics, none of the great publishers and a new kind of holy art very different from the more earthy Brueghels.

The new city hid the old city away. It would always be a great port, but the glory years were not so visible – or known. That is why I ignored the friends who kept asking rather plaintively why on earth I was writing about Antwerp. I knew it was a star of a city whose story was largely untold, a lost city to be rediscovered and given its due.

I did have a legend: the sideways references to the glory days in many documents, in Lisbon and Zurich and London and Seville as much as Antwerp – and in Florence, because Cosimo de Medici followed Antwerp gossip as well as buying pictures and horses there. I had an ancient, tattered map of sorts: the city records of Antwerp have a gap from the days in 1576 when mutinous, murderous soldiers set fire to the town hall. I had to explore records across Europe, but then as a foreigner, I needed the reports of other foreigners who had to explain Antwerp to the people at home.

I hope I found the life in the glory years, that the extraordinary Antwerp I found is buried no longer. And from my limited experience of tropical rivers, I found that the Thalys is almost too easy a route to a lost city.