The Flanders region is heavily dependent on the river Meuse, which flows over 900 kilometres north from France to the Netherlands via Belgium. The region draws drinking water from the river and uses it to irrigate fields in the surrounding area. However, climate change is threatening the delicate balance in the region.

Low water levels in the region in 2019 and 2020 have already threatened drinking water supplies in the past. Belgian newspaper De Standaard now warns that in the coming decades, drinking water supplies could disappear altogether.

A study conducted by Dutch think-tank Deltares, states that some 7 million Flemish and Dutch people rely on the Meuse for their drinking water. In Flanders, 40% of drinking water is drawn from the Albert Canal.

There are fears that global warming and reduced rainfall will impact this vital body of water. The Meuse is mostly replenished by precipitation and rainfall has reached record lows during the summer months. As the planet gets hotter due to the effects of global warming, the Meuse may begin to drain at alarming rates.

De Staandard says that by the end of the century, during the summer months, the flow rate of the Meuse could drop by a half. In a worst case scenario, by up to 70%. “In almost all climate scenarios, the Meuse flow decreases in the summer months,” Marjolein Mens, an expert at Deltares, told Dutch newspaper NRC.

A critical situation

At any given time, Flanders has around 3 weeks of water held in reservoirs. Beyond that, the region is in trouble.

Shortages of drinking water are, of course, a critical issue – but so too is the economic impact of declining water levels in the river. The Meuse is a vital economic corridor between the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. Shipping on the Albert Canal creates thousands of jobs in the Belgian economy.

Furthermore, 470 million cubic metres of water from the Meuse are used in Flanders each year. 140 million is used for providing mains water, 204 million is used for industry, 100 million for agriculture, and 20 million is used for the production of energy.

Agreements struck between the Netherlands and Belgium mean that Flanders must assure a guaranteed flow of water north of 60 cubic metres per second. If it falls below this, then 10 cubic metres is set aside to protect the river’s ecology. The remaining 50 cubic metres is shared between Flanders and the Netherlands.

If the rate falls below 30 cubic metres, then the Dutch-speaking regions are in trouble. Flanders and the Netherlands would have to make do with just 10 cubic metres per second each. Under current usage statistics, Flanders requires 15 cubic metres of water per second for all its needs. 4 cubic metres per second go towards drinking water, and 7 towards industry.

“With a supply of only 10 cubic metres, we are faced with a water shortage,” says Patrick Wilems, hydraulic engineer at KU Leuven, in a comment to De Standaard. Flemish consumers would be asked to reduce or stop their water use entirely.

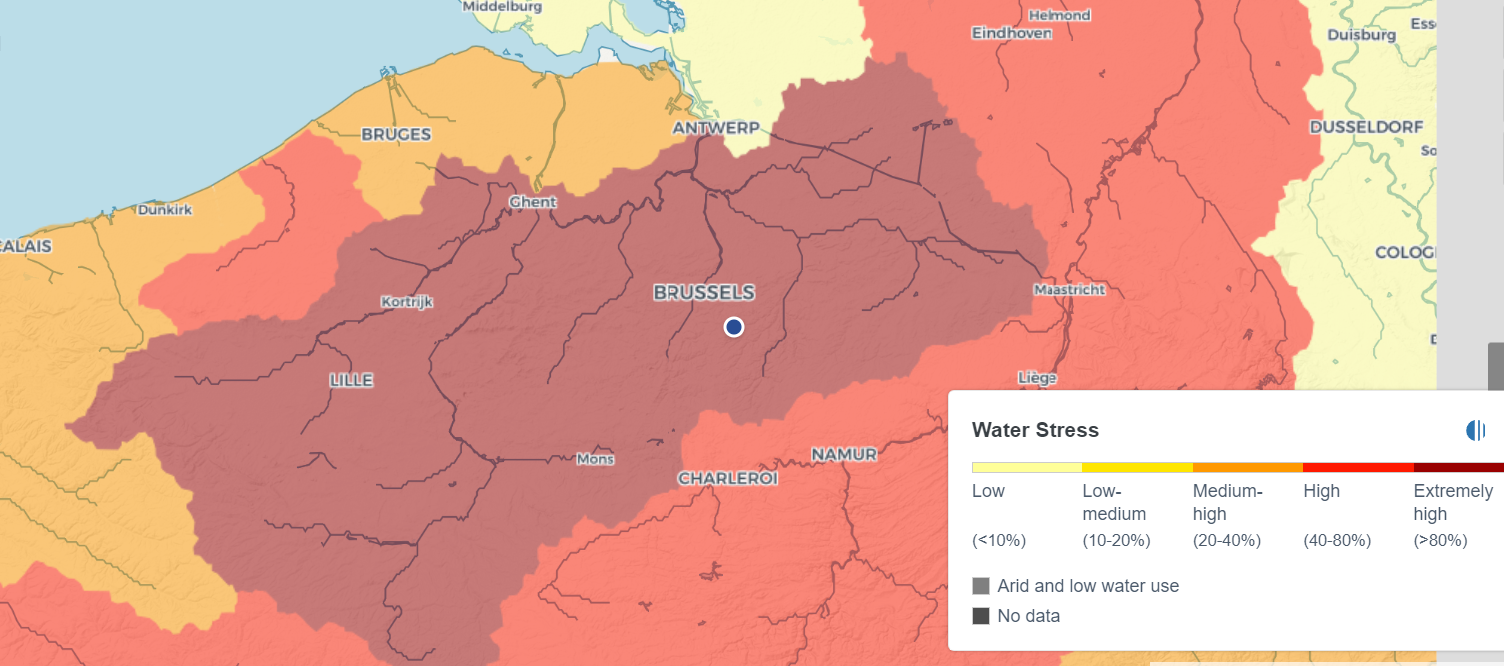

Levels of water stress across Belgium. Credit: Aqueduct/WRI

The economic damage of such a reduction, which is looking increasingly likely with global warming, would be around €450 million per day. Far from being a distant, potential problem, Belgium has almost reached critical volumes in the past. In 2019, the Meuse’s flow rate reached 35 cubic metres per second. In 2020, it came very close to 30.

“Actually, we're already in trouble from 40 cubic metres, because then Flanders is only allowed to extract 15 cubic metres, which is already insufficient. While the Netherlands still has large reservoirs to draw from, such as the Biesbosch, Flanders does not,” said Willems.

Regional authorities are already raising the alarm about the drinking water situation across Belgium. Groundwater in Flanders is dangerously low, major Belgian cities are in a precarious drinking water situation, and experts warn that no end to drought in Belgium is in sight.