Russia has been accused of interfering in the upcoming Italian elections (25 September) after Russian Foreign Affairs Director of Information Maria Zakharova made provocative comments about Italy’s energy plan, released last week.

Zakharova stated that the plan, which will reduce Italy’s dependency on Russian oil imports, is being “imposed by Brussels” but did not provide any evidence to her statement.

The claims were swiftly dismissed by the EU as “crazy statements by Russian personalities.” The EU insisted that it has excellent cooperation with Member States and that nations are working together to “respond to the challenges created by Russian actions.”

East vs West

Zakharova also criticised Italy’s relations with the United States, stating that Italy is being “pushed towards economic suicide” by the Euro-Atlantic "sanctions frenzy." Russia’s Foreign Affairs spokesperson said that “when the hard-working Italian companies collapse, they will be bought cheaply by the Yanks.”

She threatened that there will be consequences for the Italian economy as a result of joining in sanctions, referring to the number of Russian tourists who visit Italy and the trade of luxury goods.

Maria Zakharova in 2017. Credit: Council of the Federation of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation / Wikimedia Commons

Yet Italy's Foreign Affairs Minister Luigi Di Maio called the comments an “interference” in Italian sovereignty and its election campaign, and called on all Italian political forces to reject Russia’s attempts to sway the election.

This week, Gazprom (the Russian state gas distributor) released a video with images of an ice age engulfing Europe this winter after turning the gas ‘taps’ off. While this was not directed at Italy specifically, with voters heading to the ballots in under 3 weeks it can be seen as a propaganda stunt to sow distrust about the Italian establishment and sanctions.

Tit for tat

In July, when Italy's Prime Minister Mario Draghi resigned, Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that the political crisis was an internal affair of Italy, and that "Moscow had nothing to do" with it. "We will not interfere in any way," Peskov stressed.

Moscow, however, had already intervened, having called for the new Italian government not to be “subservient to American interests,” as was said by Foreign Affairs Minister Maria Zakharova when speaking to the Italian news agency AGI.

"This is an internal affair of Italy," she said, "but since the Italian Foreign Affairs Minister has dared mention Russia in the context of the government crisis, I will state that I wish the Italian people choose a government that doesn't just serve American interests." Moscow had already been described by Italy's Foreign Affairs Minister Luigi Di Maio as "celebrating the weakening of Italy."

Another incident in July saw the Deputy Chairman of the Russian Security Council Dmitri Medvedev call on Europeans to "punish their idiot governments" at the ballot box.

Minister for the South, Mara Carfagna, took to Twitter: "Medvedev should also explain which European countries he is referring to, given that the only one about to vote is Italy," while also seemingly forgetting about Sunday's Swedish elections.

Too close for comfort?

Leader of the Democratic Party (PD) Enrico Letta, in response to the comments made by Russian officials in the build up to the September elections, questioned the 2017 collaboration agreement between Salvini's Lega and Putin's United Russia parties: "This agreement must be cancelled… it is a serious threat to the sovereignty of our country."

Letta is leading the centre-left voting bloc, and during the election campaign has, on various occasions, called into question the right-wing bloc's ties to Russia.

Former Italian Prime Minister and close Putin ally Silvio Berlusconi, running again as the leader of Forza Italia in the right-wing bloc, was the first Western leader to be welcomed in Putin’s Sochi home in 2002; the two have been seen holidaying together throughout the years.

Vladimir Putin and Silvio Berlusconi in Crimea in 2015. Credit: Press Service of the President of Russia / Wikimedia Commons

Vladimir Putin and Silvio Berlusconi in Crimea in 2015. Credit: Press Service of the President of Russia / Wikimedia Commons

Berlusconi also went on a controversial visit to the Russian-occupied Crimea region with Putin in 2015. “In Crimea people thank [Putin] with tears in their eyes for what he’s done.” He was later banned from Ukraine for three years by the country’s security services.

Berlusconi now claims that the relationship between them has soured.

Links between Italian far-right and Putin

Until Russia's invasion of Ukraine this year, far-right Italian parties such as the Brothers of Italy and Matteo Salvini’s Lega had often expressed their admiration for Vladimir Putin.

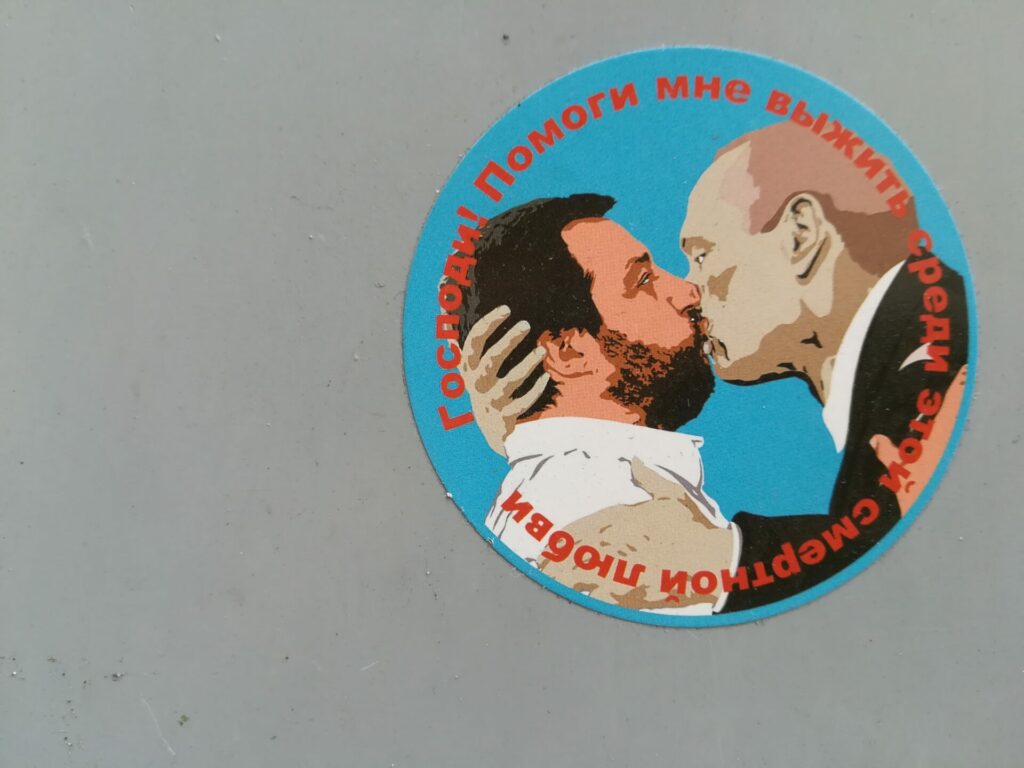

Credit: Matteo Salvini / Facebook

Matteo Salvini’s Lega party is currently implicated in an ongoing investigation for corruption dubbed “Moscow-gate.” Audio leaked by BuzzFeed revealed how Lega representatives met with Russian officials in 2018 to buy and sell a large consignment of oil. The funds would be used to finance the Lega party's coffers.

Matteo Salvini was later forced to deny that his party had sought millions from Russian investors via a secret oil deal.

Just after the invasion of Ukraine, Salvini's courting of Putin came to a head, after he was confronted by a Polish mayor with the same Putin t-shirt worn by Salvini outside the Kremlin and in the European Parliament.

Also running for Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni of the far-right Brothers of Italy party congratulated Putin in 2018 on his disputed election victory, claiming that “the will of the people in these Russian elections appears unequivocal.”

Sanctions divide the right

Both of Italy's far-right leaders have distanced themselves from Vladimir Putin’s war, with Meloni playing up a more Atlanticist role in a signal to Washington as she leads national polls. At a business conference in Italy this week, she claimed that China would be the real winner if Russia were to win the war in Ukraine.

For his part, Matteo Salvini has appeared less hawkish on the issue of sanctions. “Let's carry on punishing the aggressor, but let's protect our businesses and our workers. Winning the election and inheriting a country on its knees would not be very satisfying."

Giorgia Meloni, Matteo Salvini and Silvio Berlusconi. Credit: Presidenza della Repubblica / Francesco Ammendola

Salvini and Meloni have also disagreed on other aspects of the Russian sanctions which risk an unsustainable chasm within the right-wing coalition. Salvini stated that he was against further sanctions, the visa ban and Europe's energy challenge to Russia. Meloni has frequently alleged that Salvini's Lega party is in dialogue with the Kremlin.

The apparent lack of trust between Salvini and Meloni also comes down to the fact Brothers of Italy have eclipsed Lega in the polls. In another strange twist, Giorgia Meloni has been towing an Atlanticist line in order to appeal to Brussels and Rome institutions and distancing her party’s very direct ties with neo-fascism.

While many may believe this all to be genuine, the plan is rather most likely to be part of a three pronged-approach by the right-wing bloc, with Meloni the Atlanticist, Tajani the European institutionalist and Salvini the pro-Russia extremist, the usual sceneggiata.