Waterloo is a well-preserved battlefield, but even with its monuments, museums, and guided tours, and in some cases because of them, it is difficult to imagine what it looked like on June 18, 1815, when more than 150,000 soldiers pitched into a life and death struggle.

Just as challenging, for conflict archaeologists like me who spend their time exploring the aftermath, is envisaging the scene once the fighting was over.

Since 2015, the charity Waterloo Uncovered has helped with the necessary time travel, bringing archaeologists, historians, military veterans and students to the battlefield. As a team we have scoured places like the farms at Hougoumont, which was attacked by the French throughout the day, and Mont St Jean, which served as Wellington’s field hospital, for traces of that epic event.

We have found much, in the form of musket balls, buttons and other metal objects dropped during the battle, and in 2019, we made our most spectacular discovery, just outside the walls of Mont St Jean. There, the ongoing work of Waterloo Uncovered has revealed a long trench containing the remains of human legs amputated by military surgeons, the skeleton of a buried soldier and the remains of three badly wounded horses, each of which had been shot in the head to put it out of its misery.

The evidence we have recovered has shed new light on the battle, but what has surprised us is that since 2015 we have found just one burial site, despite checking geophysical anomalies in areas where we suspect the disposal of the dead took place, such as outside the south gate at Hougoumont.

Before the Mont St Jean excavation only one human skeleton had been uncovered by archaeologists, and that was in 2012 when work on the new museum was being monitored. These excavated remains have recently been added to by bones from the village of Plancenoit, which for a long time had been in private hands.

It’s still not a lot though, given upwards of 20,000 men were killed in the battle, and then there are the horses, of which between 6,000 and 10,000 died, some of them, like those we excavated, after the battle was over.

Battlefield tourists

In seeking an explanation for this relative absence of graves, we have turned to the archives and accounts of the battlefield written by early visitors. The story they tell is an incredible one, and in its way as much so as the battle itself.

Yes, Waterloo today is a popular tourist attraction, with around 300,000 people visiting every year, but its reputation as a must-see destination began almost as soon as the gun smoke cleared. The final defeat of Napoleon was seen as a cause for celebration by many nations, not least those represented on the field. For some in Britain especially, where troops represented only a third of Wellington’s army, it was seen as a patriotic duty to visit the battlefield.

Some of those, such as Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron, were famous, but they were relative latecomers, with Scott visiting in August 1815 and Byron in May 1816. Lesser names were quicker off the mark, arriving early enough to witness the harsher realities of the aftermath. Some of those early tourists wrote about their time on the field, and these documentarians included women like Charlotte Eaton, who visited on July 15, just under a month after the battle. As part of her tour, she walked the ground between the tavern at La Belle Alliance and the farm at Hougoumont. Writing in Waterloo Days: The Narrative of an Englishwoman Resident in Brussels in June 1815, she expressed her horror at what she saw:

In some places, patches of corn nearly as high as I am was standing. Among them, I discovered many a forgotten grave, strewed around with many melancholy remnants of military attire. While I loitered behind the rest of the party, searching among the corn for some relics worthy of preservation, I beheld a human hand, almost reduced to a skeleton, outstretched out above the ground, as if it had raised itself from the grave, my blood ran cold, and for some moments I stood rooted to the spot, unable to take my eyes from this dreadful object, or to move away: as soon as I recovered myself, I hastened after my companions, who were before me, and overtook them just as they entered the wood of Hougoumont. Never shall I forget the dreadful scene of death and destruction which it presented.

James Rouse's picture showing the digging of graves in the wood to the south of Hougoumont (where Charlotte Eaton walked over)

As Charlotte, who had arrived in Brussels as a tourist drawn by the prospect of a battle, got closer to the farm it became clear that the dead had not only been buried:

At the outskirts of the wood, and around the ruined walls of the chateau, huge piles of human ashes were heaped up, some of which were still smoking. The countryman told us, that so great were the numbers of the slain, that it was impossible entirely to consume them. Pits had been dug into which they have been thrown, but they were obliged to be raised far above the surface of the ground. These dreadful heaps were covered with piles of wood, which were set on fire, so that underneath the ashes lay numbers of human bodies unconsumed.

Those relics she thought worthy of preservation included a copy of Voltaire’s novel Candide and a French Cuirassier’s armoured breast plate, which she carried around for the remainder of her visit. By the time of her arrival objects such as these were getting thin on the ground.

Harvesters and scavengers

Since the battle, a new harvest was being reaped from the fields where the wheat had been trampled flat by men and horses. This latest crop included the clothing a dead soldier wore along with every other object left behind in the battle’s wake – even the shoes from the thousands of dead horses were removed.

It took around five days to evacuate all the wounded and more than ten days to dispose of the dead, with local workers hired by the military to clear the charnel house by burying and burning. As visitors began to arrive – we would call them battlefield tourists today – these same people hired themselves out as guides, showing their clients the places where the high points of the battle occurred. Selling them souvenirs of their visit was all part of the service, with everything from buttons and badges to swords and hats sealing the deal on Waterloo becoming a place of industry.

The sandpit across the road from La Haye Sainte being used as a mass grave (also Rouse)

As with Charlotte Eaton, most of these visitors arrived a few weeks after the battle, but someone I have written about recently was there soon enough to have wounded soldiers die in his arms. He was a merchant from Glasgow living in Brussels and his name was Thomas Ker. His papers, held by the special collections department at Glasgow University, include letters to relatives in Scotland and descriptions of his visits to the battlefield written for a book never published, until now that is.

Ker is notable not just because his accounts have not before been published, but because he seems to have been on the battlefield the day after the battle, which makes him the earliest visitor known to have set his observations down on paper. If being the first was not enough, over the following months he visited no less than 18 times, which is quite a record given that most other commentators based their descriptions on a single visit. Here he is on the earliest of those visits:

No one who has not seen it can imagine how touching it was to see the dying, the wounded, and the dead, of the thousands around you, and all that were able to articulate a calling for water to drink…Allies and French were dying by the side of each other. The cries of all now demanded the compassion of the bystander without exception.

Ker was clearly traumatised by what he saw and experienced on the battlefield and might even have suffered from what we today call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). His many visits might have brought him solace, with time healing the landscape. As the scars of battle disappeared so did all those objects that for a while had become a mainstay of the local economy.

Ker was an avid collector himself and sent parcels of objects including the most desirable of trophies, a French cuirass, along with a pistol and a pair of boots to his nephew in Glasgow. Necessity is the mother of invention, however, and fake relics, including buttons made in Liège, entered the Waterloo marketplace, with La Belle Alliance becoming a veritable gift shop.

Grinding bones

Industry is a word that has already been used here, perhaps in a slightly ironic sense, and there can be no doubting its association with the next upheavals to hit the fields of Waterloo. Having mapped the location of graves described by visitors or painted by artists it was clear to me, in the light of the work done by Waterloo Uncovered, that many had disappeared.

There was a possible explanation for this. Could it be that like the objects collected as souvenirs, the bones of men and horses became another form of crop? Were they quarried out of their pits in the years following the battle to be used as fertiliser, or spread as bone meal on the arable fields of England and Scotland?

There is some documentary evidence for this, but it's a bit thin, confined to newspaper accounts from the early 1820s and perhaps the records of fertiliser imports. Whether it happened or not however this trade passes into insignificance in the light of recent discoveries made by my colleagues, Bernard Wilkin who is a researcher in the Belgian State Archives, and Rob Schäfer, a German historian.

As the 1830s arrived local agricultural practices underwent a dramatic change, with cereal crops replaced by sugar beet. As the research is showing, this didn’t just mean a change in the crops grown in the fields, it also had a profound impact on the burials beneath them.

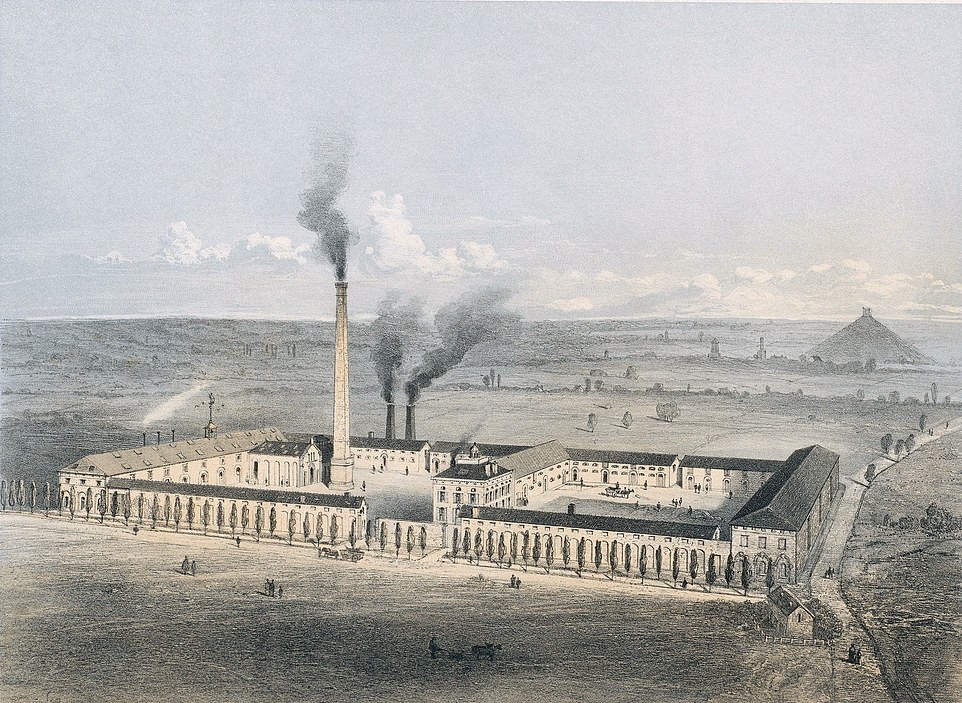

The Waterloo sugar factory. Operational from 1836 to 1971, it was later used by a dairy company. Its site is now used by Waterloo Office Park

To refine syrup produced from the beets into the sugar we stir into our coffee and tea, it needs to be filtered through a substrate, and the ideal medium in the first half of the 19th century was charred bone. There were several sugar refineries in the vicinity of the battlefield – one of them still survives as a hotel in the town of Waterloo – and all of them were hungry for this essential ingredient.

With any idea of the sanctity of the dead perhaps already dispelled by limited extraction for fertiliser, it was a short step to the wholesale despoiling of grave pits in the race to feed the sugar industry – with the market this time being domestic rather than overseas.

The uncomfortable truth about what now seems a shocking practice is captured in the archives, in legal documents providing permits to dig up graves, and fines imposed for doing so without a permit.

As the grave pit at Mont Saint Jean has demonstrated so powerfully, not all the graves were emptied during the ‘Sugar Rush’; perhaps there weren’t enough bones in it to make it worth the effort.

Our picture is still incomplete, and there is still much work to do, in the fields and in the archives, but the combination of archaeological investigation and historical research has already provided a fascinating and visceral insight into the biography of Waterloo, a place forever changed by a battle that took just a day to fight.