On a grey Belgian spring day, people in dark suits hurry up and down Antwerp’s Hoveniersstraat carrying black leather briefcases. Some pause to talk with one another for a moment, but in the city’s diamond district, everyone seems to have somewhere to be.

It might have something to do with the estimated €200 million worth of diamonds passing every day in and out of this small neighbourhood, just a few drab, architecturally unremarkable streets right next to Central Station. Dazzling stones wrested from far-flung corners of the earth’s crust land here for trading, cutting and polishing. It’s a business ecosystem with five centuries of history deeply intertwined with the local Jewish community, particularly its strict Orthodox members.

Antwerp has lost ground in recent years to Dubai and Mumbai, but an estimated 86 percent of the world’s rough diamonds still pass through this square mile at least once. An idiosyncratic mix of Belgians - Jewish or not - Indians and many other nationalities work side by side in the diamantkwartier, home to dozens of jewellers and no fewer than four diamond bourses.

Belgium’s second city is proud of this compact global hub, which faced an existential threat during Nazi German occupation. Some 25,000 Belgian Jews perished in the Holocaust; thousands more fled. After the Second World War, the neighbourhood and the diamond district pulled itself back up.

Today, according to the Antwerp World Diamond Centre, diamonds account for around five percent of Belgium’s exports and generate about 10,000 jobs in Antwerp, a city with a population of half a million.

In the streets around the diamond district

The trade organisation representing 1,600 registered companies and a direct workforce of 6,600, celebrates this unique history with the slogan ‘Diamonds & Antwerp, it’s in our DnA’.

No mention, of course, of the industry’s darker moments. Historic links to European colonial exploitation, notably in Belgium’s case of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Or more recently, at the turn of the millennium, damning revelations of the trade in so-called ‘blood diamonds’ fuelling conflict in multiple African states – an issue was eventually addressed by the UN-backed Kimberley Process, a trading scheme that certifies shipments of rough diamonds as ‘conflict-free’.

Over the last 20 years, Antwerp has gone to great pains to show it has cleaned up its act, reinventing itself as the hub with the world’s highest regulatory standards – the natural choice for those looking to do ethical trade. “A firm belief in integrity is the very foundation of what constitutes the success of the Antwerp diamond industry,” the AWDC campaign charter states.

Deal or no deal

However, since the outbreak of war in Ukraine, Antwerp traders face a new dilemma: whether to deal in rough diamonds from Russia, a leading global producer that happens to be waging a brutal military campaign on its neighbour.

Doing so is legal in the European Union for now, but courts controversy. When luxury Russian goods like premium caviar and vodka were blacklisted for import after the invasion in February 2022, rough diamonds were quietly omitted from the EU sanctions list, round after round.

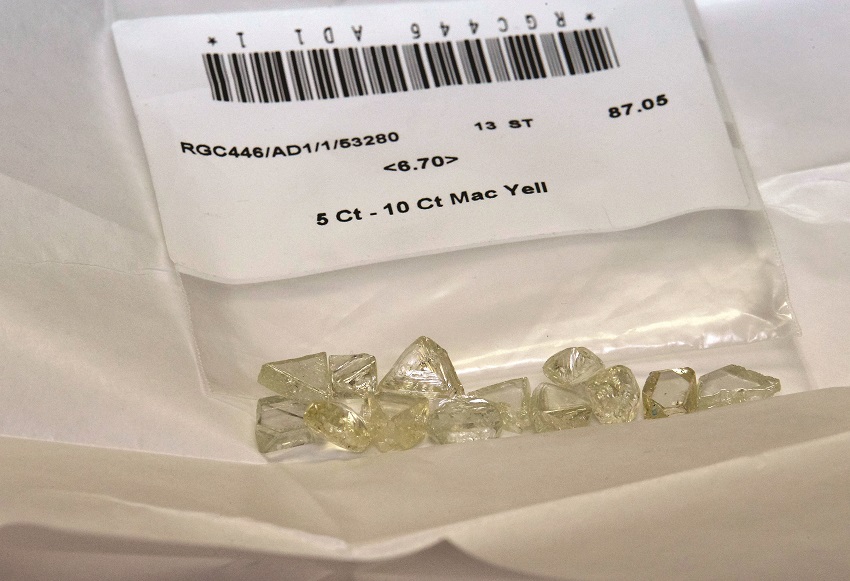

Uncut diamonds

While the United States banned many imports over a year ago, Belgian National Bank figures show the country shipped in €1.4 billion worth of Russian diamonds last year, down from €1.8 billion in 2021.

Antwerp has faced fierce criticism for indirectly funding Russia’s war - most diamonds are mined there by state-controlled giant Alrosa - but perhaps the most embarrassing jab came from Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky. “I think that peace is more valuable than diamonds in shops,” he said during his address to the Belgian Parliament in March last year.

Business is business

Given the bad press and strong public sentiment, diamantaires are highly reluctant to speak publicly. “It’s not something we would ever say to people, but to survive we sometimes do have to buy Russian diamonds,” an Antwerp diamond industry source admits on condition of anonymity.

His company used to get about 30-40 percent of its diamonds from Russia. That is now down to “pretty much zero,” he says.

“Everybody hates and is against Russia in this war,” he insists while adding that sometimes, personal feelings have to be put aside. “People are in business to do business,” he says pointing to the ground already lost by Antwerp to other hubs with laxer rules. “We have to be opportunistic.”

In 2021, the year before the war in Ukraine, Belgium was the number one destination for Russia’s $4 billion diamond export market.

A lot has changed since then: Russian diamonds, which made up 25 percent of Antwerp’s trade in a normal year are now less than five percent – and all without sanctions, the AWDC says.

AWDC spokesperson Tom Neys argues that a total EU import ban would be catastrophic for many Antwerp diamantaires. “If you were a small diamond trader and you have always traded in Russian diamonds, for example, and suddenly you can’t sell it anymore…Yeah, you're out of business,” he says.

AWDC spokesperson Tom Neys

In the AWDC’s Hoveniersstraat office, Neys has laid out stones in different cuts: rectangular, teardrop and square. These days 95 percent of cutting is done in India, though the biggest diamonds are still handled by Antwerp’s specialists. Given the risk of shattering a stone and the amount of money at stake, some cutters take six months to study a gem before they get to work.

But the main problem with EU sanctions, AWDC says, is that they would not hurt Russia. “If Europe has sanctions, Russian diamonds will be selling exactly the same. You will have zero impact,” Neys says. “The only thing you will have done is that all these companies in Antwerp will move to Mumbai…You will lose complete control of the diamond industry.”

Hans Merket, a researcher from the International Peace Information Service, partly agrees with the AWDC. “The US sanctions haven't had the full effect they should have, but they had some effects,” says Merket, who investigates links between natural resources and conflict. One analysis suggests that Alrosa’s revenue was down €1 billion last year, although likely not down to sanctions alone.

What is indisputable is that this is an industry with extremely complex and mobile supply chains. Most of the world’s diamonds come from eight or nine mining companies whose chosen customers fight hard to hold on to their coveted direct access.

As gems make their way down the chain from mine to shop window or factory floor (most diamonds are used in industry, not jewellery), they might change hands 20 or 30 times as traders hunt for specific characteristics. “The four Cs: carat, colour, cut and clarity,” Merket explains. The many steps make tracing a diamond’s origin challenging, even if one cares to try.

We don’t know because we don’t care

In Antwerp, jewellers sell items to suit all tastes. Shoppers can browse everything from a classic, sleek engagement ring to a gem-encrusted Kalashnikov-type assault rifle on a thick gold chain.

Simon Tikva has been running his jewellery business for 25 years, taking over the mantle from his parents. The shop specialises in diamonds, though he can’t say where the ones he’s selling are from. “We don’t know because we don’t care,” he says, peering through wraparound magnifying eyeglasses at the clasp of the string of tiny rubies he is mending. Generally, they come from Congo, Botswana and Russia, he adds.

Simon Tikva studying the stones

Origin determines the price of other stones, like emeralds, but not so much for diamonds, Tikva explains. “The price for us, for everybody here in Antwerp, is much less in other places in the world. Because there’s the bourse and we buy the diamond directly from the bourse.”

Most jewellers approached are extremely reluctant to speak about Russian imports. One, who asked to be identified only as Mr A, was nonplussed by the entire debate. “It’s all bullshit,” he scoffs, pointing to continuing imports of Russian oil and gas into the EU.

“The funniest thing is that African diamonds are more war-related than Russian ones,” he says. Even if sanctions on Russian rough diamonds were imposed in the EU, they would still find their way to Antwerp and elsewhere, the 26-year-old claimed.

No way back

Nonetheless, a joint G7 initiative is being developed to deprive Russian President Vladimir Putin of potential war-chest revenue. The exact details are yet to be thrashed out, but the aim seems to be to introduce a traceability mechanism as well as a G7-country import ban to collectively wipe out a huge chunk of the global consumer market. Industry insiders say such a solution would impact all trade hubs and not just Antwerp, sharing the burden more fairly.

Whatever happens, the Antwerp diamond industry source is bracing for change. “We know that at some point in a very short while there's going to be probably greater limitations placed on Russian diamonds and we have to prepare for the future,” says the Antwerp diamond industry source. At the same time, he expresses hope that the war will end, things in Russia will change and business can resume.

Still, as the conflict grinds on, many major jewellers are already turning their back on Russian diamonds, and traders are aware of this, IPIS’s Merket says. “The initial idea was really let's just sit out the storm,” he says. “It's becoming clear that there's no going back to business as usual.”