The curves showing the daily increase in confirmed infected persons and fatalities still refuse to flatten.

A first light at the end of the tunnel is the daily number of new patients in the hospitals that have decreased a few days in a row. The number of patients in intensive care units has also been stable.

Besides single hospitals that have run out of respirators and been forced to transfer patients to other hospitals, the Belgian hospital system does not yet have to ration care. The situation can however deteriorate and force medical staff to apply ethical guidelines on what to do in such situations.

According to the latest figures from Sciensano, the Belgian institute for health, 420 patients with COVID-19 were hospitalized during the last 24 hours, which brings the total number in hospitals to 5,840 in a total of 104 hospitals around the country.

Of those patients, 1,257 are in an intensive care unit, which actually was a decrease by 4 compared to the previous day. Most of them need a respirator and a small number need Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO).

According to professor Steven Van Gucht, the figures do show some improvement or a plateau in the curves but it is necessary to see how it will develop during this week.

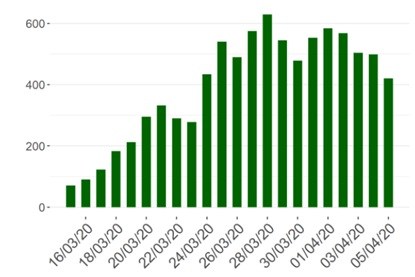

Graph: Daily number of new cases of hospitalised patients, source: Sciensano

Life and death decisions

Doctors in other countries, e.g. Italy and Spain, might already have had to take life and death decisions on their own without any ethical guidance. In New York, where there is a shortage of ventilators, Dr. Michel Katz, the head of the city’s public hospital system, said that none of the facilities he oversees had yet to prioritize who gets a ventilator.

“To my knowledge, no ethical system would ever use age as a sole criterion,” he said according to The New York Times (3 April).

In Belgium, the Belgian Society of Intensive Care Medicine issued ethical principles on “proportionality of critical care” already last month (update 26 March).

The society writes that it was not within its mandate to draft national ethical guidelines and recommends that hospitals draft their own guidelines. However, that would result in non-uniform and unequal treatment of patients by the hospitals and is hardly desirable.

In the intensive care unit (ICU), invasive life-sustaining and life-saving therapies are applied to patients who would not survive without such care, because of vital organ failure. In general, intensive care medicine should be reserved for patients in whom a good or at least acceptable outcome can be expected, after hospital discharge.

According to the guidelines, under normal circumstances, even when there is no pressure on ICU beds, disproportionate care should be avoided at all times. Most patients in Europe who die in the ICU, will do so after a decision not to initiate or to withdraw life-sustaining treatments.

The society states bluntly that the COVID-19 pandemic poses a major strain on the health care system, because of the absence of herd immunity against this new virus and mentions the alarming situation in Italy. Belgium wants to avoid such a situation where treating physicians might need to decide which patients to admit, and which patients will be denied critical care.

Critical care

There are different ways to avoid this. A first priority is to take the right measures to maximize capacity in the ICUs of all hospitals, by postponing non-urgent medical care, and transforming non-critical units into critical care units. But this would of course require more resources, both respirators and the medical staff required for managing the units.

However, when in spite of these measures, the health care capacity to treat all presenting patients is still insufficient, there is a need for ethical considerations on whom to treat (triage).

Age plays a role but is not the only factor. “Although an increased age is associated with worse outcomes in COVID-19, age in isolation cannot be used for triage decisions, but should be integrated with other clinical parameters. Frailty and reduced cognition, more than age, are independent predictors of outcome when elderly patients are admitted to the ICU.”

To avoid last minute decisions in an acute setting in hospitals, the society proposes that the situation in retirement homes should be mapped. Many of the residents there suffer from moderate to severe frailty according to the society.

An advanced care plan should be discussed with residents of retirement homes, or their relatives, in advance. Such a plan should contain, at least, statements whether or not it is desirable to initiate a number of life-saving treatments.

“In view of the predicted acute overload of the Belgian healthcare system during the COVID-19 epidemic, the Belgian Society of Intensive Care Medicine recommends that patients for whom critical care would be disproportionate, are identified early, to avoid that they are sent to an overcrowded hospital unnecessary.”

If this might seem as brutal decisions, denying frail people at retirement homes with low chances of prolonging their lives of access to hospital treatment, the situation in a hospital differs.

The society writes that the decision in the hospital whether to deny or prioritize care should always be discussed with at least two, but preferably three physicians with experience in the treatment of respiratory failure in the ICU. Consultation with a geriatrician or the general practitioner of the patient could also be an option.

“Many COVID-19 patients will be elderly, but age in itself is not a good criterion to decide on disproportionate care. Priorities should be decided based on medical urgency.” Whether the wish of a severely ill or dying patient will be respected is not clear.

Last October, representatives of the three Abrahamic monotheistic religions presented a position paper to Pope Francis on the end of life and euthanasia. Only when death is imminent despite the means used, would it be justified to make the decision to withhold certain forms of medical treatments that would only prolong a precarious life of suffering, according to the position paper.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times