Cohesion is the glue that holds Europe together. If member states are not willing to cooperate and citizens not willing to interact, the European project is in danger. Lack of cohesion undermines EU’s capacity to formulate and implement policies. A recent study on structural and individual cohesion shows interesting but also worrying trends in a ten-year perspective in EU and its member states. The study was presented by political scientist Josef Janning, head of the Berlin office of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), at a policy dialogue arranged by the European Policy Centre (EPC) in Brussels (21 February). He has developed a tool, the EU Cohesion Monitor, which captures cohesion on both macro and micro levels in the member states.

“We looked at factors that influence the willingness of countries and citizens to cooperate in the EU context,” he explained. “In this second study more data were available and we could analyse the changes between 2007 and 2017. During this period Europe was hit by two severe crises, the financial crisis in 2008 and the refugee crisis which started in 2015.”

Methodologically each member state received a score for ten indicators which were treated with equal weight. The indicators are based on a number of sub-indicators or factors with data collected from open sources such as official statistics and opinion research.

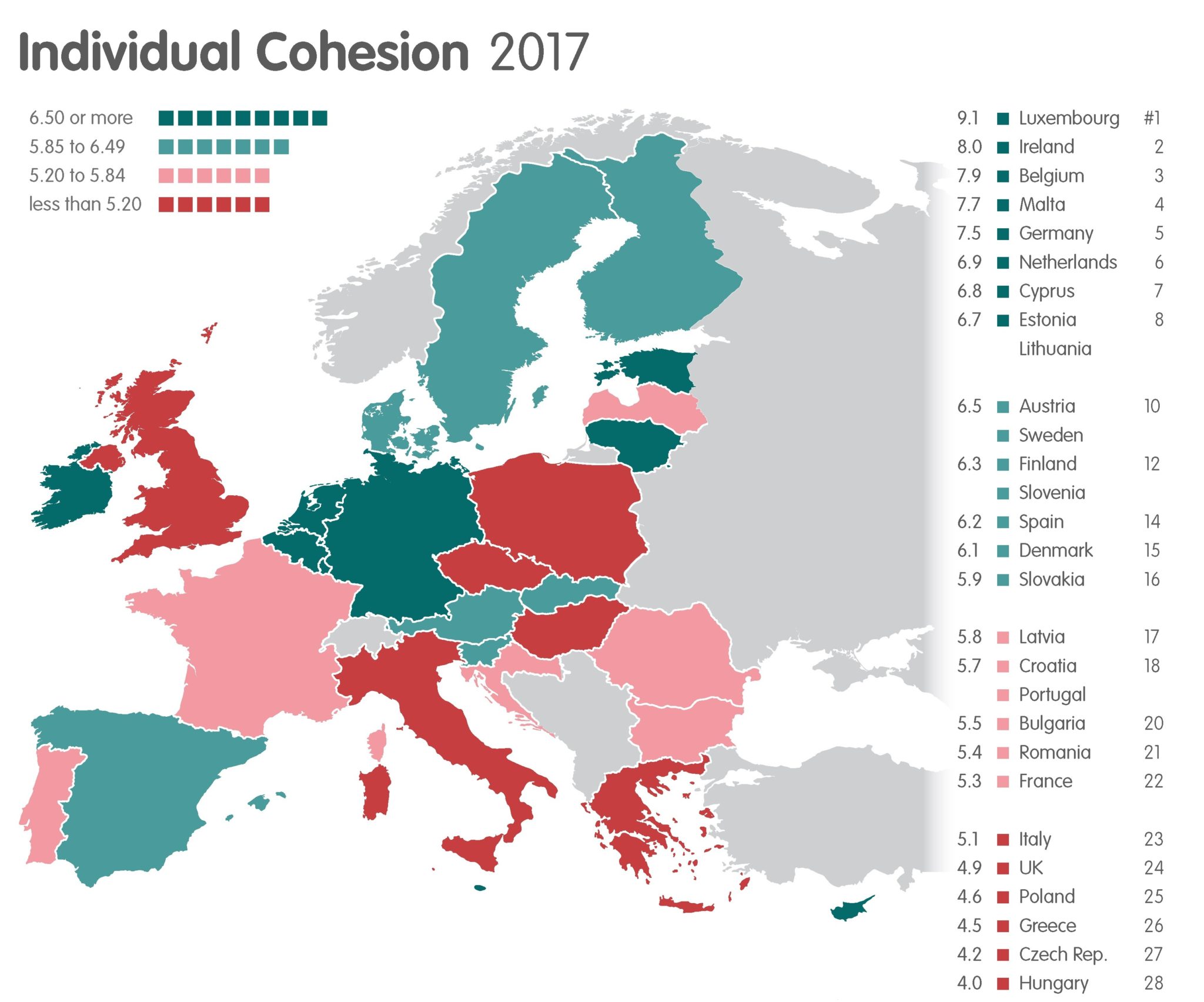

Structural cohesion was measured by economic factors such as the size of intra-EU trade and financial flows involving the EU budget but also by member states’ willingness to cooperate on common policies. Individual cohesion was measured by citizens’ interaction with other EU countries, turnout in elections to the European Parliament and attitudes to EU.

Asked by The Brussels Times about the correlation between individual EU-related cohesion and domestic cohesion, for example trust in government and participation in civil society organisations, Janning replied that there probably is a strong correlation but it had not yet been factored in.

The structural factors have pushed countries in different directions but ordinary people are less aware than the elites of how much EU funding their countries are receiving. Even if they were, it does not necessarily translate into support for EU. What is of special concern, according to Janning, are countries with low individual cohesion, because it implies a shattered belief in EU.

More broadly, there have emerged two divides that reflect the political debates on EU’s future. As regards structural cohesion there is an east-west split in the EU that reflects the financial assistance given to the new member states in central-eastern Europe. The other large-scale trend is a north-south divide in individual cohesion.

Some countries defy the trends. Ireland and Portugal incurred serious economic damage during the economic crisis but their levels of individual cohesion have increased. Poland and Hungary saw significant increases in structural cohesion but their individual cohesion declined. This development started already before the refugee crisis but was exacerbated by the crisis.

© ecfr.eu

Danuta Maria Hubner, an MEP from Poland and former Commissioner for Regional Policy, agreed that the two crises have had an impact on cohesion. “We were relatively united in tackling the financial cricis but our reaction to the refugee crisis was more varying and reflected different perceptions of national interests.”

“We haven’t yet seen the end,” she said and warned that the lack of individual cohesion will lead to changes in next elections to the European Parliament. While objecting to putting Poland and Hungary in the same basket, she admitted that the state of individual cohesion in both countries is also a matter of political will on part of Eurosceptic governments.

Law professor and social activist Alberto Alemanno wanted to add his home country to the watch list. “No party in the coming elections in Italy (4 March) has taken a clear pro-EU stance,” he said. “One third of the news in the election campaigns are fake.”

On the bright side he noticed that overall cohesion has increased in EU and this could be seen as a sign of the Europeanisation process when being members of the EU. That said, there is no room for complacency, he warned. “Presenting EU as an inevitable project and neglecting citizens’ demands is probably the worst thing we can do.”

“Today Europe’s greatest deficit is not democratic, but of intelligibility.” He is in favor of improving the European Citizens Initiative (ECI) as an avenue for citizens to set the political agenda of the EU in between elections.

This instrument of participatory democracy entered into force in 2012. It requires at least one million citizens from at least seven member states to sign a petition to the European Commission to propose new EU legislation in any of the areas of EU’s competences. But according to Alemanno, despite its democratic potential, the ECI has shown poor results.

What can be done to strengthen cohesion in the EU? The speakers seemed to agree that cohesion-building measures should be tailor-made to the member states and that special attention should be paid to countries experiencing problematic trends. Focus should be put on individual cohesion which has a greater potential for short-term growth than structural cohesion.

M.Apelblat

The Brussels Times