All of Brussels can be seen as an open-air museum with streets, squares and parks adorned by historical statues and memorials, mostly meant to represent and even glorify Belgium’s past. But for a long time, one monument in memory of Belgium’s colonial rule in Africa has been missing. This was partly corrected this year on 23 April 2018, when Brussels City Council decided to name a square after the tragic figure of Patrice Lumumba.

When Belgian Congo gained independence in 1960, Lumumba became the country’s first prime minister, only to be murdered shortly afterwards in a plot with Belgian involvement, while Congo descended into chaos despite the presence of United Nations peacekeeping forces. It would take Belgium 40 years to decide to investigate its post-colonial role in the affair and to admit its moral complicity in the murder. But still justice has not been served.

Colonial history in the public space

A Patrice Lumumba Square has been long requested by African and Congolese communities in Brussels and their supporters. The ongoing renovation and “decolonization” of the Africa Museum in Tervuren – scheduled to be reopened in December 2018 – seems to have set something in motion in Belgium and testifies to changing times and a reassessment of history (see The Brussels Times Magazine, issue 25).

Strong voices from the Matongé quarter in Ixelles resulted in street actions, with interest groups even placing faux street name boards. In fact, already in 2015, a Futur Place Lumumba was showing up in the quarter on Google Maps, adjacent to the Saint Boniface Church.

The origins of Matongé trace back to the opening of an Africa House (Maison Africaine) in 1961, where Congolese students were hosted. Since the Matongé quarter was in fact already in name connected to a commercial district in Kinshasa, some opponents to a square thought that this was already enough recognition.

The Ixelles Municipality Council disagreed on naming a square in Matongé after Patrice Lumumba. It claimed that it could “incite violence” in the heart of a neighbourhood of people with African roots. The neighbouring City of Brussels, however, cut the Gordian knot. Following its decision, part of Bastion Square close to the Namur Gate and Avenue de la Toison d’Or was renamed Patrice Lumumba Square. It is expected that the square will also get a statue of Lumumba to reinforce its identity.

The memorial plaque says that Lumumba was assassinated on 17 January 1961 alongside two of his ministers, Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, but without mentioning the perpetrators or those responsible.

The decision by the City of Brussels is the first of its kind in Belgium. It commemorates Belgium’s colonial past in the public space and can be seen as a sign of respect towards Congo’s people. Although it wasn’t a quick or easy decision, all went smoothly and the square was inaugurated on 30 June 2018. In other parts of Belgium, groups are pressuring to have their own Lumumba Squares or a street named after him, as other countries already have done.

Historical background

On 30 June 1960, Congo suddenly became free from colonial rule by Belgium, as the Republic of the Congo, but without being much prepared for it. Independence was preceded by a long history of colonial rule, starting in the 1880s as the private possession of King Leopold II under the facade of the Congo Free State. As of 1908, it was as an official colony of Belgium.

The abhorrent crimes of the Leopold II era were ended and a broad national project was started in Congo. The end of World War II in 1945 sparked the decolonization of the African continent. In 1958, the anti-colonialist Mouvement National Congolais was founded in Belgian Congo.

Following a nationalist rally by Patrice Lumumba in December 1958, having visited the All-African Peoples' Conference in Ghana, his political rival Joseph Kasavubu of the ABAKO party organised his own gathering a month later. The rallies resulted in protests against colonial rule and were severely suppressed.

Riots in Léopoldville (today’s Kinshasa) in January 1959 quickly set change in motion for Congo. The independence movement gained support for the political parties outside the major cities. A week later, Belgium’s government realized the changing tide. It was already arranging for Congo’s independence “but without undue haste.”

Lumumba arrives in Brussels 26 January 1960 for a Congo-Belgian roundtable conference shortly after the Belgian government’s decision to agree that Congo would become independent on 30 June 1960. © National Archives of the Netherlands

At the first Congo-Belgian Round Table Conference in January-February 1960 in Brussels, the Belgian government agreed that Congo would become independent on 30 June 1960 - only four months away. Lumumba, only 35 years old, was still imprisoned for having caused the recent upheaval but was quickly released by the government and flown to Brussels. There he acted as a uniting voice among the divided Congolese delegates.

In May, elections took place in Congo. By June, the Congolese government was formed, headed by President Kasavubu and Prime Minister Lumumba. The new state was minimally prepared for independence and Belgium left many internal problems to the Congolese people.

Independent Congo’s first government, 24 June 1960. © RMCA Tervuren

From the first day on, during the independence ceremony itself, a rift between Belgium and Congo became quickly evident. King Baudouin talked about the “genius” of his forbearer King Leopold II and praised the progress Congo had made under Belgian rule. He did not feel the need to address the atrocities that had taken place in the early period, such as mutilations, forced labour and economic exploitation.

Paternalistically, he added: “Don't compromise the future with hasty reforms, and don't replace the structures that Belgium hands over to you until you are sure you can do better. Don't be afraid to come to us. We will remain by your side and give you advice.”

Lumumba had carefully prepared his own speech, which was actually not planned to take place. He saw Congo’s independence as liberation, won by a “day-to-day fight” to “put an end to the humiliating slavery, which was imposed upon us by force.”

From independence to civil war

On 1 July 1960, the Congolese army (the Force Publique) mutinied against their Belgian commanders, who were still unwilling to step down. News of violence against Belgian citizens spread and Belgium sent troops to Congo to restore order. This was seen by Congo as a violation of their agreement of friendship with Belgium.

To make things even worse, the provinces of Katanga (led by Moise Tshombe) and South Kasai rebelled against the central government, backed by Belgian funding and troops. They declared themselves independent on 11 July. In this way, Belgian mining interests were protected from the turmoil in the rest of Congo but, more importantly, a large part of the economic wealth was cut off from the central government.

The legitimate Congolese government pleaded for help from the United Nations, headed by Swedish Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld. Following United Nations Security Council resolution 143 on 14 July, UN peacekeeping troops under the command of another Swede, Major General Carl von Horn, were sent into Congo.

Although the resolution called on Belgium to withdraw its troops from Congo, they remained in place “for humanitarian reasons”. In resolution 161 on 21 February 1961, the UN forces were authorized to use force, “in the last resort”, to restore order and secure Congo’s territorial integrity.

Carl von Horn, who had threatened to resign because of the confusion in the UN headquarters in Léopoldville, was soon replaced by an Irish general. Von Horn would later write a book where he criticized the UN and described his own mission as a failure.

Hammarskjöld, who was authorised by the Security Council to provide the Congolese government with military assistance, ignored Lumumba’s desperate appeals for help and refused in the beginning to deploy UN forces in Katanga, since he saw its secession as an “internal conflict”. Instead, he preferred to negotiate with Tshombe. When he died in September 1961 in an airplane crash, he was on his way to meet him. That same year, Hammarskjöld was posthumously awarded the Nobel peace prize.

In August, finding no help from the West and the United Nations, Lumumba asked the Soviet Union for support to free his country. The Soviet Union sent weapons and 1,000 “technical advisors”.

This seems to have sealed Lumumba’s fate. The United States feared that Soviet influence would spread across Africa and planned CIA missions to overthrow Lumumba’s regime. In the atmosphere of the Cold War in the 60s, Lumumba was seen as a dangerous Communist.

The execution of Lumumba

By September, the situation in Congo had become even more confusing. Following a telegram from Belgian Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens, Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba as Prime Minister. In turn, Lumumba declared President Kasavubu deposed.

Due to the political impasse, army chief colonel Mobutu stepped in and took power with his troops, Armée nationale congolaise (ANC). He placed Lumumba under house arrest in his residence, guarded by both ANC and UN troops. Lumumba managed to flee by hiding in a car, but was captured on 1 December by the ANC and imprisoned. UN forces did not intervene to free him.

On 17 January 1961, Lumumba was brought to Katanga by the ANC, urged to do so by Belgian Minister of African Affairs Harold d’Aspremont Lynden, allegedly because it was feared that he could be freed by his supporters. A few weeks earlier, the Belgian Parliament had held a discussion where members had warned that bringing Lumumba to Katanga into the hands of his enemies there would spell his death sentence.

His arrival, together with former ministers Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, was overseen by Belgians. During the transport and upon arrival, the three were savagely beaten and tortured. Within five hours after his arrival, they were brought to an open spot in the savanna. The Katangese had already decided their fate.

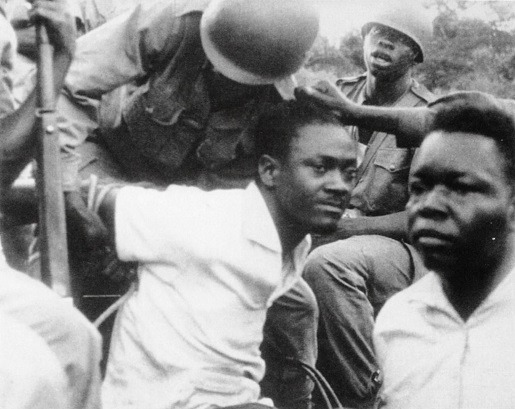

Soldiers of Colonel Mobutu's forces roughly manhandled ex-Congo Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba after his arrest (5 December 1960). © National Archives of the Netherlands

Here Lumumba, an African independence visionary for some, a Communist for others, was killed in the presence of Katangese President Tshombe, two Kantangese ministers as well as Belgian officials and police officers. Three separate firing squads were reported to have been assembled and commanded by a Belgian, Captain Julien Gat.

Another Belgian, Police Commissioner Frans Verscheure, was in overall command. The bodies were thrown into a quickly hollowed-out pit. The next morning, Katangese Minister of Interior Godefroid Munongo ordered Belgian police officer Gerard Soete to make the bodies disappear. Soete has described the gruesome acts of hacking up the bodies and destroying them by acid and fire.

Lumumba’s death was only communicated a month later, on 13 February, by the Katangese government. Minister Munongo spread the lie that the three prisoners had escaped, killed their guards and made off in a getaway car. After a nationwide search, they were recognized by villagers, who beat them to death.

The international left blamed Brussels, and Belgian embassies were attacked in several capitals. The civil war in Congo (1960-1965) claimed the lives of about 100,000 people.

Belgian self-inspection

A book by Belgian sociologist Ludo De Witte, published in September 1999, sparked controversy. In it, the author blamed Belgium to be solely responsible for Lumumba’s death. Already in December 1999, a proposition was made in the Belgian Parliament to establish a commission of enquiry to “determine the exact circumstances of the assassination of Patrice Lumumba and the possible involvement of Belgian politicians.”

The commission began its work in March 2000. By May, six Belgian academic historians were appointed, joined by another one from the University of Kinshasa. Ludo De Witte was also invited. In September, a specialist in encryption was given the task to study coded telexes dating from the period. Access to non-public institutions like the Royal Archives was granted.

The investigators were given unprecedented clearances to study still classified state documents. After 18 months of work, the report was presented in 2002. In 2004, it was published as a book for the general public.

The parliamentary report stated that Belgium acted under pressure of the Belgian public, which had heard for days about violence against Belgian citizens in Congo. According to wide sections of the population, one person was held responsible: Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. The public demanded a very strong response from the government.

Rather apologetically, the report urges readers to see the developments in light of the Cold War in the 60s, “with different standards, ethics and norms.” It points out that the decolonisation in Congo was quickly enacted and was “unforeseen by Belgium,” despite the fact that other African nations had already gained independence.

It confirms that, after Congo had become sovereign and independent on 30 June 1960, “this did not stop Belgium and a number of other countries from intervening directly in its internal affairs,” even when “the non-intervention principle was already part of international legislation in 1960.”

Because of “the presence of large numbers of Belgian officers and officials, a close connection” between Congo and Belgium remained. More importantly, a large majority of these “felt they were expected to play an important role in the construction of the new state.” The government “did not always and completely keep them informed.”

After the complete split between both governments, Belgium attempted to influence the creation of a new government. Minister of Foreign Affairs Pierre Wigny sent a diplomat to Congo to plan a coup. And Minister Ganshof van der Meersch, who was in charge of the transition period in Congo, sent a state security agent “to work behind the scenes” to destabilize Congo.

The report states that “the Belgian government showed little respect for the sovereign status of the Congolese government.” By aiding Katanga, it favoured a “confederal reorganization of Congo.” The commission confirmed that secret funds (about 7 million euro today), managed by the Ministry of African Affairs, were used to finance the policy against the Lumumba government.

In Katanga, the actions were supported by the Union Minière, a Belgian mining company, which “tried to finance military or paramilitary groups.”

The Belgian actions gained momentum during the second half of August 1960. The report indicates that the Belgian General Consulate in Brazzaville was “encouraging the opposition or providing logistic support.” Belgian Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens asked President Kasavubu to “sack Lumumba” and “was given legal advice” to do so.

The report sees the Belgian actions as “one element in a wider group of opposition forces.” The “split between the Congolese Prime Minister and the UN Secretary-General” is considered crucial.

The commission saw little success of a Belgian or even American intervention “without the existence of internal opposition within Congo itself.” Congo was “a vast country” and “extremely diverse on all levels.” After supporting the deposition of Lumumba, Belgium “was eager to prevent him from returning to power,” says the report. Therefore, they “insisted on his arrest.” Mobutu was only prepared to do so until “a Belgian promise to provide technical and military support to ANC”.

Plans to kill

The report also states that it was “absolutely clear that there were plans to kill Lumumba” and that there was “no trace of an order to rescind these plans.” It was certain that “the Belgian government tried to take Lumumba prisoner and transfer him to Katanga.” More importantly, there were “no signs of concern about the physical safety of Patrice Lumumba.”

After he was arrested, “the Belgian government never insisted on a trial.” The report noted that “no one should be taken prisoner except on the order of a judge or after the decision of a court.”

King Baudouin was aware of a letter from Major Guy Weber, military adviser to Tshombe, noting “that the life of Lumumba was in danger.” However, “no evidence has been found that either the government or the competent ministers were informed of this letter.”

According to the report, there is no evidence that the Belgian counsellors in Katanga “were involved with, or consulted during the decision-making process that led to his execution.” The execution was carried out “under the authority, leadership and supervision of the Katangan authorities” by Katangan gendarmes or police officers and in the presence of “a Belgian police commissioner and three Belgian officers.”

However, at no time “did the Belgian government protest […] the unlawful execution of Lumumba, Mpolo and Okito.” Even later on, with some members of the government aware of the execution, “any knowledge of the fate of Lumumba was still denied when confronted by public opinion” or during “private meetings with NATO partners.”

Following the report, the Belgian government admitted in 2002 to having had “undeniable responsibility in the events that led to Lumumba’s death.” However, the government did not take full responsibility and issued a public pardon of the Belgians involved in the assassination of Lumumba.

Lumumba’s son Roland brought a court case in January 2001 in Kinshasa against Belgium “for hiding its role in the murder.” In 2010, the sons of Lumumba appealed again and started a case in a Brussels court. According to them, the order for the murder was directly given “by Brussels.”

In July 2012, the federal prosecutor's office deemed the case was acceptable to court, based on the genocide law of 1993. By December 2012, this was confirmed by the Indictments Chamber, which paved the way for the investigations to start.

In January 2016, it was reported that a tooth of Lumumba was confiscated in the former home of police officer Gerard Soete. In his 1978 novel, he had described the taking of two teeth, two fingers and bullets from the body. Later on, he declared that he had thrown them into the sea. He died in June 2000 during the parliamentary enquiry.

For De Witte, this proved that Soete’s home – as an accomplice in making Lumumba’s body disappear – was never searched. Nobody involved has ever been tried before a Belgian court. It is clear that the last page about the execution of Lumumba has not been written and will probably never be.

| History reassessed: Is Belgium ready to face the truth about its involvement in the assassination of Lumumba? The Brussels Times asked historian Dr. Mathieu Zana Etambala, scientific adviser to the Africa Museum in Tervuren, about his opinion. “There are still Belgians who are nostalgic about the period of Belgium’s rule in Congo," he replies. “They don’t want to hear a negative word about Leopold II and do not tolerate the slightest criticism of Belgium’s colonial policy. Nor do they have the least understanding that the murder of Lumumba was largely the result of Belgium's political interference in an independent, albeit young and inexperienced nation.” But he thinks that this group of Belgians is getting smaller while criticism about the colonial past is getting louder. ”Remembrance education is also gaining more and more impact.” Has historical research since the official Belgian enquiry disclosed any new findings? “The findings of the parliamentary enquiry have been made public. As is often the case, the facts are no longer debated, but rather their interpretation. Perhaps this is also normal when a ‘guilt question’ is asked.” “It’s interesting to notice that further research is being done on other connected issues,” he adds. Within a few months, a study will be presented at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) with new information, based on previously unpublished sources, about the “Katangese Secession”. Based on the official enquiry, Etambala considers the Belgian government politically and morally responsible for the actions of numerous Belgian officials and agents who, after the independence of Congo, operated in the country and were involved in the execution of Lumumba. But he admits that it is almost impossible to prove who the real perpetrators were. There are letters and telegrams, but telephones were also used, and information was transmitted through secret agents and intermediaries. “That King Baudouin held a grudge against Lumumba is widely known. That he had some sympathy for Tshombe is equally true. But, he was by far not the only one. If he wanted to get rid of Lumumba, he needed the cooperation of the government,” Etambala says. |

By Tom Vanderstappen