In recent years, pressure has been growing on European museums to return artifacts taken from Africa during colonial times. When the Royal Museum for Central Africa reopened after its renovation in 2018 under the brand name AfricaMuseum, diaspora protests called for the restitution of colonial collections.

These demands are not new. They have a long history that dates back to Congolese independence in 1960 and even before. What is new is the wave of research on the origins of colonial collections, and several projects – both academic and artistic – reflect on the larger cultural loss the removal of these objects caused in their communities of origin.

(Re)Making Collections: Origins, Trajectories & Reconnections, a recent bilingual volume that I co-edited with Didier Gondola from the Johns Hopkins University and Agnès Lacaille from AfricaMuseum, takes stock of provenance research – including on the collections of the AfricaMuseum.

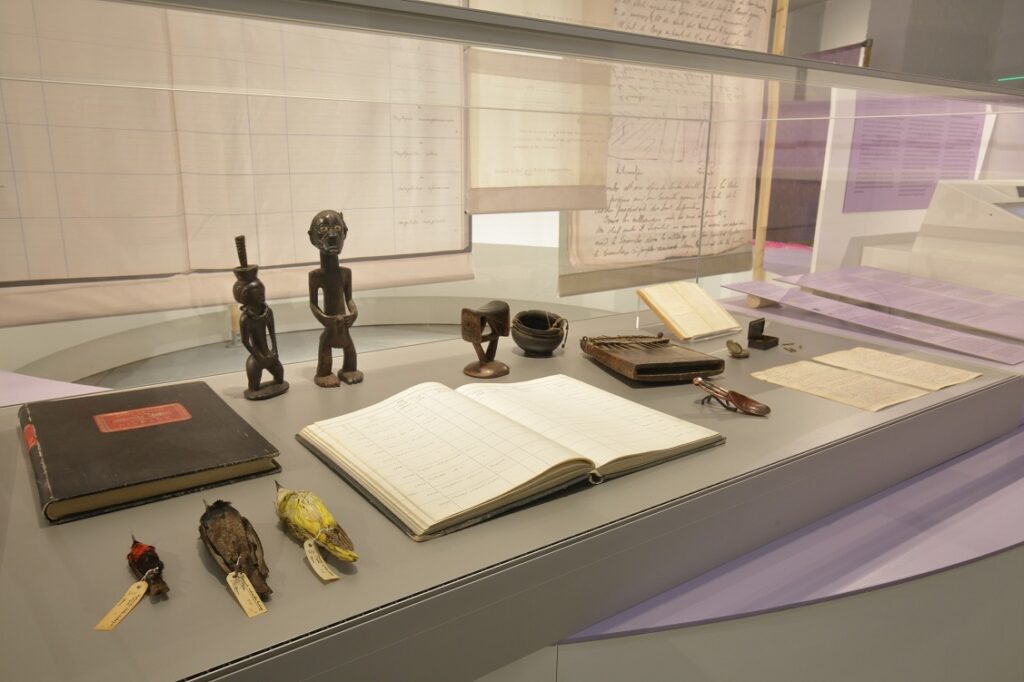

It features a range of contributions from authors in Europe, Africa and the US, and explores what we know about the colonial histories of the museum’s collections, how we know it, and what we should do with the newly gained information. AfricaMuseum subsequently used the book as the inspiration for a new exhibition, ReThinking Collections, which runs until the end of September.

Provenance research broadly means researching the histories of objects: where they come from, how they were used, and so on. Both the book and the exhibition are interested in a particular kind of provenance: how were objects removed from their African contexts?

Rethinking collection, the exhibition at Africa Museum

This might seem at first glance like an academic exercise, but it is a historical question with considerable societal relevance today. It is part of the broader set of questions about Belgium’s colonial past and its long-term consequences we are confronted with today.

A 2022 law for the restitution of colonial collections from Belgium’s former colonies sets out a key role for provenance research and is backed by the €2.3 million budget for the AfricaMuseum (although the law only applies to federally held collections).

Stolen stories

Although the exhibition only covers a selection of studies from the book, they both follow the same structure, opening with the question of sources and methods: where and how can we learn about the histories of these objects?

What sources and methodologies are used? Although colonial archives are an important source of information for provenance research, only on occasion do they contain exact information about how, where and from whom objects were removed.

However, there are other ways of using archives. The exhibition shows how the existing inventory of the museum can be analysed for general trends and patterns in the acquisition of objects. This shows, for example, that 60% of the objects from Congo ended up in the museum before the First World War.

Take, for example, the necklace, known to be held in the 1930s by Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu, a Songye chief, which is now in the collection of the museum. Archival sources indicate the necklace made its way to the museum after the execution of the chief for criticising the Belgian occupiers.

The necklace once owned by Songye chief Kamanda

But vital research by Donation Dibwe dia Mwembu, a history professor at the University of Lubumbashi, shows us the importance of oral histories and memories. The testimonies of the late chief’s descendants – Ytal Yambo, Agnès Kalonda, and the current chef – reveal the deep and generations-long trauma of the lived experience of colonialism. Chief Kamanda’s presence in Congolese popular culture, and notably popular paintings, shows that he lives on in the region’s collective memory.

The case of the necklace, as well as other contributions in the book, notably the research on collections of human remains by Lies Busselen, demonstrate the limitations of archival research and the importance of involving communities of origin and their recollections and memories in provenance research.

Kamanda's necklace

The exhibition includes three case studies in which provenance research successfully showed how objects ended up in the collections of the museum.

The first involves the skulls of elephants collected by an agent of the Congo Free State in a frenzy of killings and captured in morbidly arranged photographs.

The second, from the museum’s archaeological collections, is about funerary objects removed from the grave of a local chief, Matanga, in what today is Kongo Central province. While researching the collection, Nicolas Nikis and Alexandre Livingstone Smith found a signed agreement in which archaeologist Maurice Bequaert promised to return the objects to the village. He broke that promise: museum collecting did not end with the independence of African countries.

In the third case, the former head of the museum’s ethnography department Anne-Marie Bouttiaux reflects on her experience buying newly made masks in the Ivory Coast, raising questions about the possibility of ethical collecting: even in a postcolonial context, it is difficult to avoid unequal power relations.

Research’s limits

Even though most of the exhibition shows the possibilities of provenance research and several cases in which it has been used successfully, it is still important to recognise its limitations.

Given the time and cost of this type of research, it will not be possible to research entire collections. And even if we could research them, many objects will remain essentially silent: we will probably never find out how they were removed from their contexts of origin because that information is simply lost to time – another colonial legacy.

We must therefore disconnect the results of provenance research from restitution since such an approach would disqualify large portions of collections from returning.

And while an object can be returned, the damage done by its removal is less easily addressed. This is the subject of the last part of the exhibition and book. The removal of an object can leave a void and have long-standing consequences for certain practices or bodies of knowledge. Visitors to the exhibition can see a work by Géraldine Tobe, a young artist from Kinshasa whose work addresses the issue of loss, particularly of ancestral spirituality, engendered by colonialism.

Another striking example is the work of Adelia Yip, who explains how the removal of manza xylophones in north-east Congo meant much more than the loss of an object. It resulted in the loss of the knowledge and cultural memory embedded in this type of instrument. Although such a loss can never be repaired, Yip created a digital replica of a manza and its sound that can be shared.

Meanwhile, Plaice Mumbembele, a University of Kinshasa anthropology professor, reflects on the return to Congo of a kakuungu mask, and the different meaning the return took on for different stakeholders.

These examples show the importance of placing Congolese questions and desires central in processes of return and restitution. The process of translating the content of an academic book into an exhibition was not easy, and several questions remain open. For example, should the AfricaMuseum continue to display objects which we know were removed with violence or under pressure?

Whose expertise counts in these matters? Are we overly focused on academic expertise, and is it time to listen to other voices? Although the answers might be tricky, hopefully a book and exhibition like this one can be a starting point.