The story begins in 1940. The German army has swept through France and Belgium. Despite the Miracle of Dunkirk in May-June, when nearly 340,000 Allied troops are evacuated across the Channel, hundreds are pinned down by the German advance and left behind.

Those avoiding capture go into hiding, often staying in safe houses provided by locals who face severe reprisals if discovered.

Belgians determined to fight on are also trapped as the occupation forces secure beachheads and harbours. Those able to bail out are also marooned behind enemy lines.

The situation looks desperate, but help is at hand – from an unlikely source.

In early 1941, Andrée ‘Dédée’ De Jongh, a 24-year-old advertising designer-turned-nurse, meets Resistance fighter Henri Debliqui and his cousin Arnold Deppé, a cinema engineer for Gaumont, recently returned to Belgium from Saint-Jean-de-Luz in south-west France, close to the border with semi-neutral Spain.

Together, the three hatch an ambitious plan for an escape route that becomes the Réseau Comète, or Comet Line. Its long tail will wind from Brussels to Paris then down to Bayonne, across the Pyrenees and into Spain. But before they can launch their plans, Debliqui is denounced by a notorious traitor, Prosper De Zitter, and shot.

Dédée and Deppé are fortunately not exposed and press on. They receive crucial financial backing from Jacques Donny, secretary of the Belgian company Sofina (Société Financière de Transports et d’Entreprises Industrielles). Nicknamed ‘Père Noël’, Donny had already been organising clothing and shelter for Allied servicemen on the run.

In June 1941, Dédée and Deppé mastermind the escape of two French prisoners of war, Charles Morelle and Henri Bridier. The men – and the hundreds who will follow them – were given refuge near Bayonne by a Belgian couple, journalist Elvire De Greef, alias ‘Tante Go’, and her husband Fernand, known as ‘Oncle Dick’. The pair, who fled Brussels with their teenage children, Freddie and Janine, become a lynchpin of the Line.

Andree De Jongh

Two more escapes are planned in July and August. Without a boat, the first crosses the River Somme, tying a rope to each bank and use an inner tube. The group crosses the Pyrenees but most are later arrested by the Guardia Civil, handed to the Germans or sent to the infamous Miranda de Ebro concentration camp.

During their second mission, the Gestapo arrests Deppé and two Belgians at a café near Lille railway station. Later deported, he survives the war. But Dédée crosses the Pyrenees and dangerous Bidassoa River with Ernest Sterckmans, Robert Merchiers and Scottish soldier Private Jim Cromar. She escorts the latter to the British consulate in Bilbao, where she asks if the Allies will back Comet.

She proposes 6,000 Belgian francs and 1,400 Spanish pesetas (around €2,500 today) for each rescued airmen or soldier. Her proposition is relayed via Michael Creswell, the attaché in Madrid, to MI9, the British War Office department aiding escape and evasion. After two long weeks, Dédée receives the answer she is hoping for.

Price on her head

By 1942, furious that Dédée has slipped through their net, the Germans put a bounty on her head. Brussels is no longer safe and she switches her centre of operations to Paris. Her father Frédéric briefly takes over in Brussels before following her to the French capital.

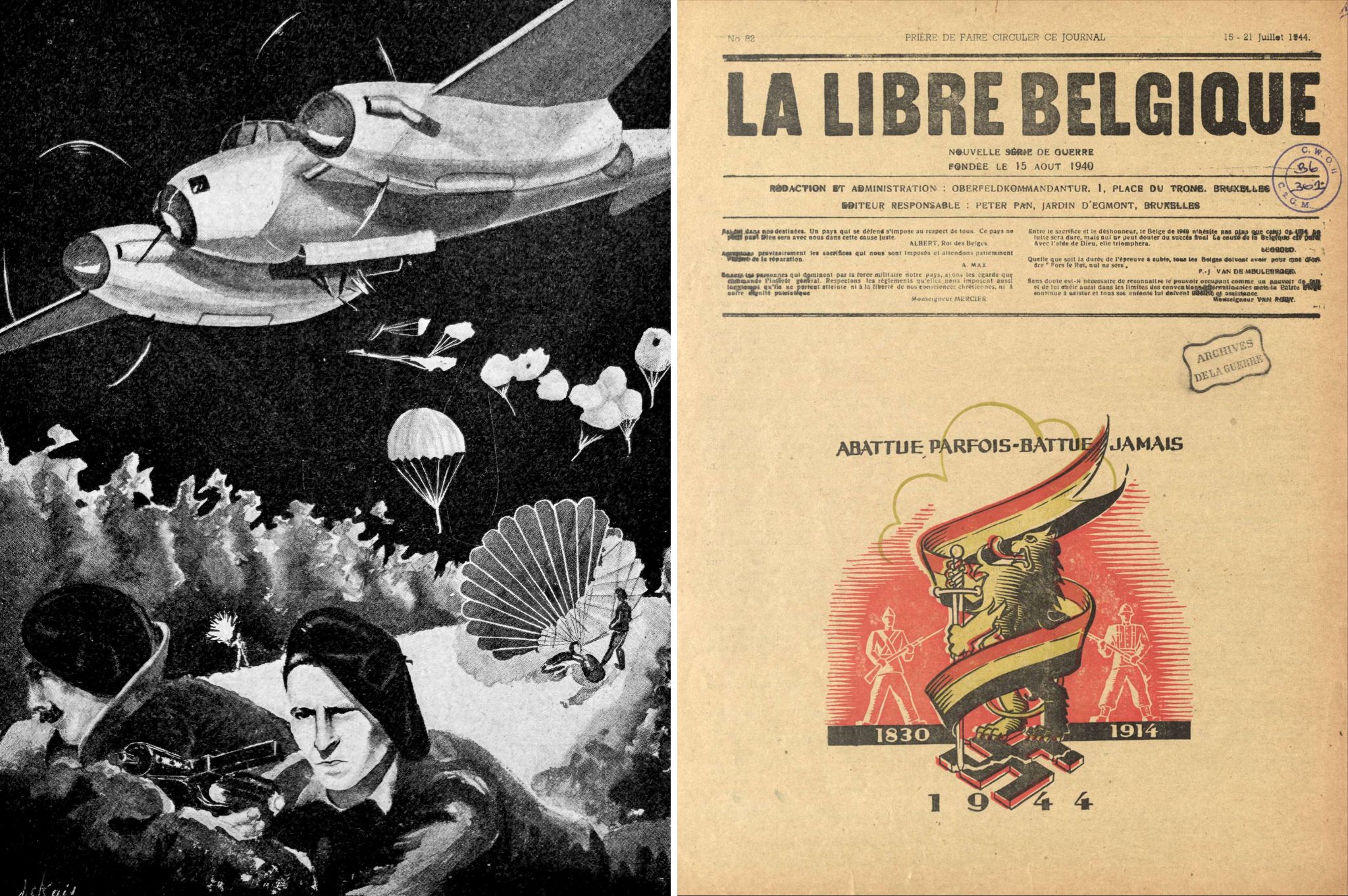

Henri Michelli, a friend, succeeds him in Brussels, but lasts less than a week after he is caught hosting a dinner for Charles Morelle, now a key member of the Line, and three agents parachuted in from London.

Jean Greindl (‘Nemo’), head of the Swedish Red Cross children’s canteen at 9 Rue Ducale, is persuaded to take over. Ably supported by his No2 Peggy Van Lier and ‘Nadine’ Dumon, he quickly expands the operation to cover the whole of Belgium, recruiting new volunteers.

Between July and November, more than 50 Allied airmen make successful ‘home runs’ thanks to the Line. But the arrests continue. Dédée’s older sister Suzanne is picked up after a botched bid to spring Michelli from jail. Deported under the Nacht und Nebel decree, she ends up in Ravensbrück and Mauthausen but survives.

Dédée

After the morale-sapping arrest of Nadine and her parents in August, worse is to come. On November 18, Germans posing as US pilots trick their way into the Avenue Voltaire home of Georges Maréchal and his British wife Elsie. It has been a safe house for 18 months. Worried when he hears no news of the ‘pilots’, Nemo sends Victor Michiels, a 26-year-old lawyer, to investigate.

The door is answered by the Germans and Michiels makes a run for it down the slope towards Avenue Ernest Renan. He is gunned down as he reaches the corner. Georges Maréchal is sentenced to death, while his wife and 18-year-old daughter, also called Elsie, is deported.

Over the next month, the Germans arrest 100 Comet Line helpers, including Jacques Donny and Peggy Van Lier. A German speaker, Van Lier convinces her interrogators that she is innocent but is kept under close surveillance. Nemo orders her evacuation with two guides, Georges d’Oultremont and his cousin Edouard.

They cross the Pyrenees in December and make it to Britain. Georges, whose daughter Brigitte is today president of the Comet Line Remembrance Association, later serves in MI9 and the Belgian SAS.

Elvire De Greef

Dédée’s luck runs out in January 1943: denounced by a farmhand, she is arrested with her trusted mountain guide Florentino Goikoetxea and a group of airmen. She confesses that she is Comet’s head but the Gestapo refuse to believe that they have been outwitted for so long by a young woman. Dédée, who has crossed into Spain more than 30 times, is deported to Ravensbrück and Mauthausen.

Torture and execution

In yet another setback, 38-year-old Nemo is arrested in February 1943 and sentenced to death. But before his execution is carried out, he is killed at Etterbeek barracks in a US bombing raid.

Antoine d’Ursel, alias ‘Jacques Cartier’ and working for the Clarence intelligence network, succeeded Nemo. But the betrayals continue: on October 20, 11 Comet Line helpers are executed at the Tir National firing range in Schaerbeek.

Plaque for Victor Michiels

By 1944, Paris sector head Jacques Le Grelle (‘Jérôme’) and southern route leader Jean-François Nothomb (‘Franco’) are arrested. Le Grelle is tortured by the Sipo-SD, the SS police and intelligence unit. He later writes of his brutal treatment:

“Forced to undress, I was first beaten with a reed whip until my back was raw. With my ankles and knees tied and my hands cuffed behind my back, I was dragged to a bathtub filled with water. Seventeen times I had my head plunged into the water until I suffocated … I was brought back to life by equally brutal methods, such as being hung by my feet from a hook fixed to the wall. In between, wedges were driven under my fingernails. I came out with seven broken ribs.”

Dédée’s father Frédéric is executed at Mont Valérien fortress, on the outskirts of Paris, on March 28. Le Grelle and Nothomb are sentenced to death by a military court in July. Moved from prison to prison, they survive the war.

Despite the setbacks, the Comet Line continues helping airmen to escape, with the last group, three Americans and two Britons, crossing the Pyrenees on June 4, two days before D-Day.