The year is 1897 or 1898. Imagine, briskly stepping off a steamer that has just crossed the English Channel, a forceful, burly man in his mid-20s, with a handlebar moustache. With an ailing mother and a wife and growing family to support he is not the sort of person likely to get caught up in any idealistic cause. He looks – and is – every inch the sober, respectable businessman.

Edmund Dene Morel is a trusted employee of Elder Dempster, a Liverpool-based shipping line. A subsidiary of the company has the monopoly on all transport of cargo to and from the Congo Free State, as it is called, the huge territory in central Africa that is the world's only colony claimed by one man. That man is King Leopold II of Belgium. For more than a decade, European newspapers have praised him for selflessly investing his personal fortune in public works to benefit the Africans and inviting Christian missionaries to his colony.

Because Morel speaks fluent French, his company sends him to Belgium every few weeks to supervise the loading and unloading of ships on the Congo run. Morel begins to notice things. At the docks of Antwerp, he sees his company's ships arriving filled to the hatch covers with immensely valuable cargoes of rubber and ivory. But when they cast off their hawsers to steam back to the Congo, while military bands play on the pier and young men in uniform line the ships' rails, what they carry is mostly army officers, firearms, and ammunition. There is no exchange of goods, Morel realises: "Nothing was going in to pay for what was coming out."

From what he saw at the wharf in Antwerp, and from studying his company's records in Liverpool, Morel made a startling deduction. "These figures told their own story....Forced labour of a terrible and continuous kind could alone explain such unheard of profits....forced labour directed by the closest associates of the King himself....It must be bad enough to stumble upon a murder. I had stumbled upon a secret society of murderers with a King for a croniman."

This brilliant flash of moral recognition by an obscure shipping company official gave birth to one of the great human rights movements of his time.

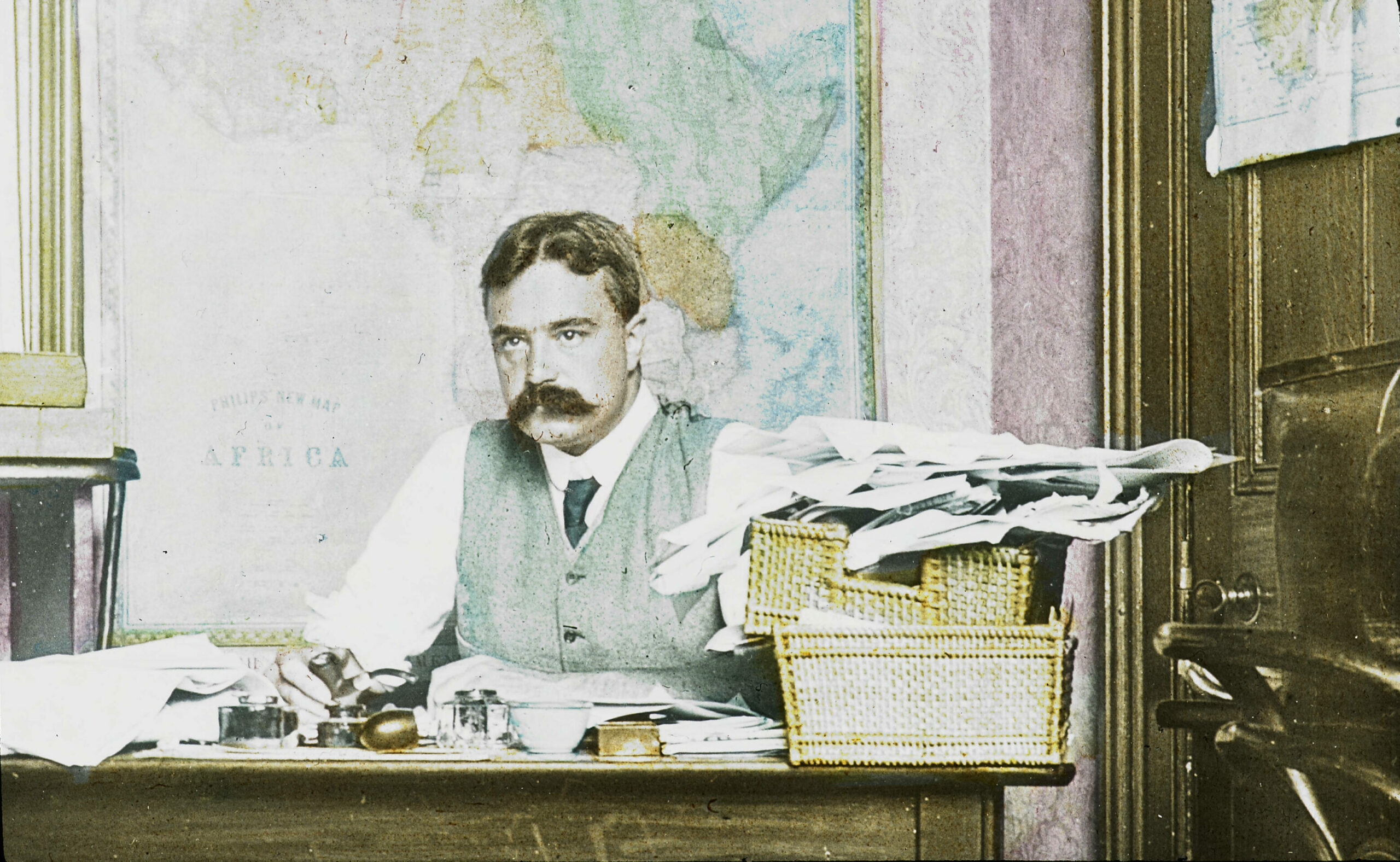

E.D Morel, ca. 1900-1915

Morel was correct. King Leopold was making "unheard of profits" from his ownership of the Congo. During the 23 years he controlled the territory, the late Belgian historian Jules Marchal estimated those profits as being well over $1.1 billion in today's dollars. The great bulk came from sales of rubber, for the equatorial rain forest that covered half the Congo was rich in wild rubber vines. The invention of the inflatable bicycle tyre, followed by that of the automobile, had set off a worldwide rubber boom. It was primarily to gather this rubber – and to gather it quickly while prices were high, before plantations of rubber trees in other countries grew to maturity – that Leopold had constructed his forced labour system.

In 1901 Morel quit his job and took up his pen, filled with "determination to do my best to expose and destroy what I then knew to be a legalized infamy." He was 28 years old.

Morel was all of a piece: his thick moustache and tall, barrel-chested frame exuded forcefulness; his dark eyes blazed with indignation. The millions of words that would flow from his pen over the remainder of his life came in a handwriting that raced across the page in bold, forward-slanting lines, flattened by speed as if they had no time to spare in reaching their destination. After learning what he had in Antwerp, he writes, "to have sat still....would have been temperamentally impossible."

Cartoon depicting Leopold 2 and other imperial powers at Berlin_conference 1884

Once he had staked out his position as the most vocal public critic of the Congo state, eyewitnesses – missionaries, and occasionally someone within Leopold’s colonial apparatus – began coming to him if they had any revealing documents to leak. The more he published, the more they leaked.

For example, Leopold's Congo agents, backed by the king's 19,000-man private army, quickly discovered that the most effective way to force men to go into the rainforest to collect wild rubber was to hold their wives hostage. But when the king’s spokesmen indignantly denied that there was any such hostage-taking, Morel reproduced in his pamphlets and articles the blank printed form in French where each agent of a big rubber company half-owned by the king had to list "natives under bodily detention during the month of __________, 1903."

Across the page were columns to be filled in for each person: "Name," "Village," "Reason for arrest," "Starting date," "Ending date," "Observations." Morel also reprinted an order from company management to all agents with instructions regarding "upkeep and feeding of hostages."

In response to increasing pressure from the public and Parliament, the British government asked its consul in the Congo to travel into the interior and write a report on conditions there.

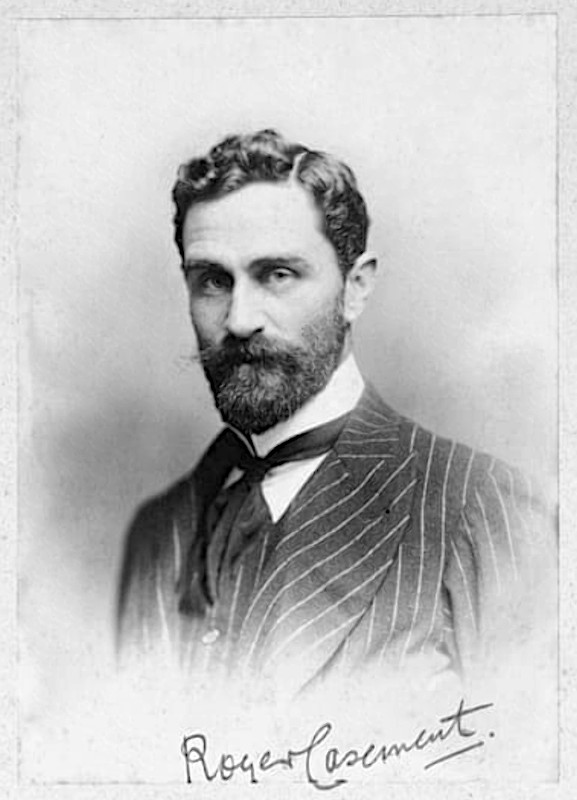

Sir Roger Casement

His Majesty's Consul in the Congo was a tall, handsome, black-bearded Irishman (Ireland was then part of the British Empire) named Roger Casement. When the Foreign Office sent him on this investigative mission, it got far more than it had bargained for. Casement rented a steamboat and spent more than three months interviewing survivors of Leopold's rubber terror. The detailed report he wrote about his findings is a landmark in the literature of human rights, a forerunner of the closely documented reports issued by organisations like Human Rights Watch today.

Casement was so outraged by what he had seen that he began giving interviews to the press. Although it tried to water down his report, the Foreign Office couldn't keep him quiet. He and E. D. Morel sought each other out and became fast friends. Still in the British Consular Service, Casement couldn't openly ally with Morel, but behind the scenes quietly helped him organise the Congo Reform Association in 1904. The crusade Morel orchestrated through it was the strongest and most sustained international human rights movement to arise between the abolitionism of the early and mid-19th century and the worldwide campaign against South African apartheid of the 1970s and 1980s.

In Liverpool, on the third anniversary of the founding of CRA, an audience overflowed an auditorium which seated nearly 3,000 and filled two adjoining halls. Cries of "Shame! Shame!" resounded at similar mass meetings throughout England and Scotland.

By 1907, there were nearly 300 protest meetings a year in the British Isles. A master of all the media of his day, Morel made a slide show a central part of most Congo protest meetings. This consisted of some 60 vivid photos of life under Leopold's rule. These pictures provided evidence that no propaganda could refute. Morel and his allies also displayed whips and shackles from the Congo.

Colonial exploitation in Congo

Morel knew the editors of most of the major British magazines and newspapers, and wrote regularly for many of them, including the most prestigious, The Times. Whenever an editor needed to send a reporter to Belgium or the Congo, he had a candidate to suggest. He fed information to sympathetic newspapers in Belgium.

With a powerful boost from Casement's report, the international campaign Morel orchestrated reached newspapers all over the world. His own meticulously kept files contain, over a ten-year period, 4,194 clippings.

The pressure he created eventually forced Leopold to divest himself of the country he considered his private property. Only one alternative was ever really considered: its becoming a colony of Belgium. If such a move were accompanied by the proper reforms – and Morel constantly insisted on these – he hoped the rights of the Congolese might then be better protected than in a secretive royal fief. The lack of alternatives to the "Belgian solution" considered may seem surprising today, but at the time the idea of independence and self-government in Africa was inconceivable to almost anyone in Europe.

In 1908, the king reluctantly turned the Congo over to Belgium – demanding, and receiving, a huge sum of money in return. He died the following year.

Sir Roger Casement

No one was more changed by his participation in the Congo reform movement than Roger Casement. "In those lonely Congo forests where I found Leopold," Casement wrote, "I found also myself, the incorrigible Irishman." While on his investigative journey in the Congo, he fully realised for the first time that Ireland, too, was a colony and that there, too, the core injustice was the way the colonial conquerors had taken the land. "I realised that I was looking at this tragedy with the eyes of another race of people once hunted themselves."

Casement was knighted for his achievements, but in 1913 he resigned from the British Consular Service and threw himself full-time into the cause of Irish independence. He was out of the country when World War I began, but a German submarine landed him on the coast of Ireland so he could rejoin his comrades in the nationalist movement. He was quickly captured and became the first knight of the realm in several hundred years to be charged with high treason. In 1916, he was hanged.

Did the Congo reform campaign save lives? Some of the worst abuses, such as the kidnapping of hostages, did stop as a result of the publicity. But the high death rate in the territory continued for more than a decade under Belgian rule. The widespread use of forced labour continued still longer, as it did – often with equally deadly results – in British, French and Portuguese colonies in Africa as well.

The Congo reformers were part of a tradition that is still alive today. It is this spirit which underlies organisations like Amnesty International, with its belief that putting someone in prison solely for his or her opinions is a crime whether it happens in China or Turkey or Argentina, or Médecins Sans Frontières, with its belief that a sick child is entitled to medical care, whether in Burundi or Honduras or the South Bronx. During its decade on the world stage, the Congo reform movement was an important link in that chain, and there is no tradition more honourable. At the time of the Congo controversy more than a century ago, the idea of full human rights, political, social and economic, was a profound threat to the established order of most countries on earth. It still is today.