Many Brussels residents know that their city has medieval roots, but far fewer are aware of the richness of the cultural life that once flourished here.

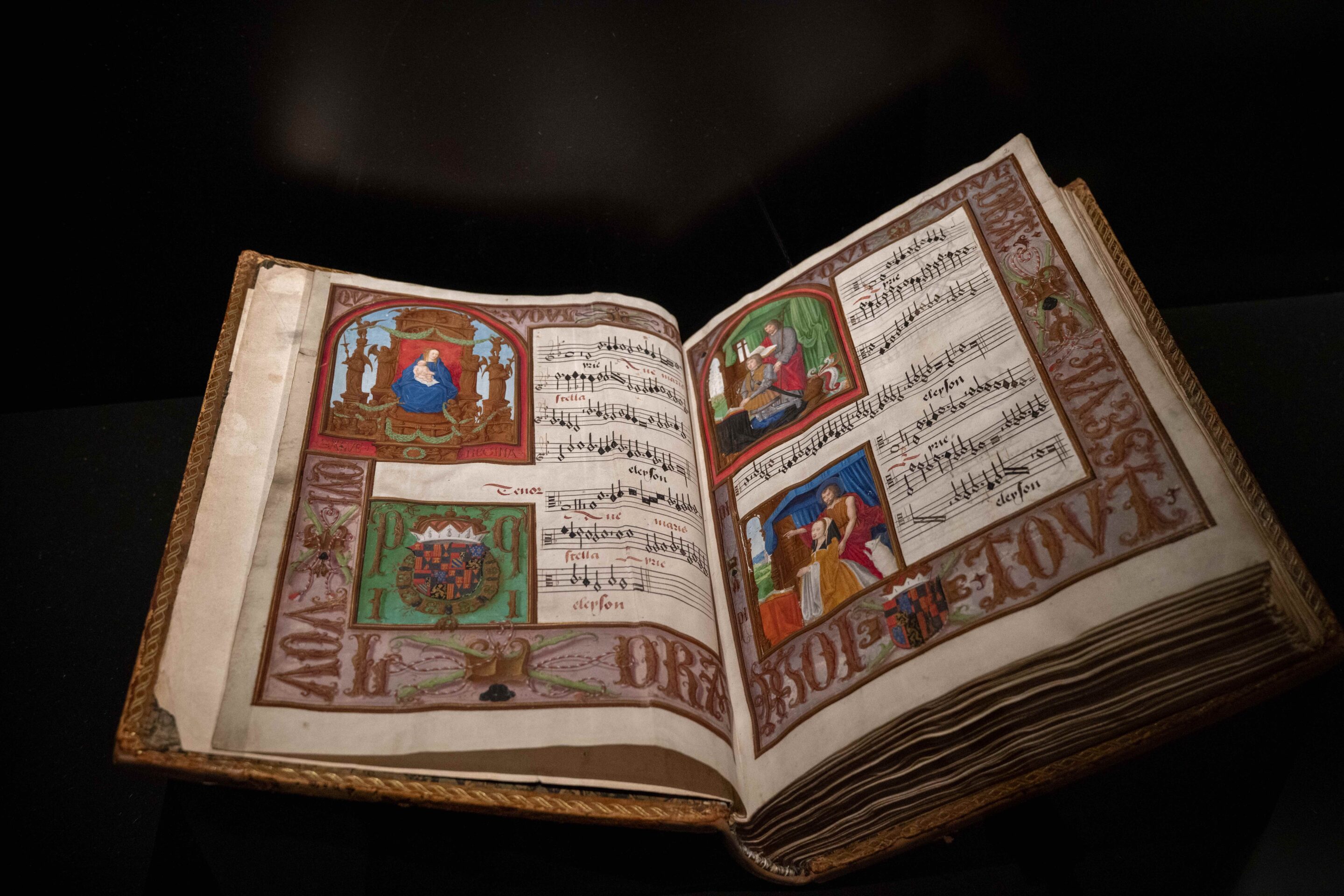

We now have a chance to learn more about what is known as the Golden Age after the Museum of the Royal Library of Belgium (KBR), which boasts a remarkable manuscripts collection from the Dukes of Burgundy, re-opened its doors after 15 months of renovation. The museum — housed within the modernist Royal Library on the Mont des Arts — also casts a spotlight on one of Belgium’s most enduring cultural legacies: its extraordinary contribution to European music, and, in particular, to the rise of Renaissance polyphony.

At the heart of the new exhibition lies the Franco-Flemish school of polyphonists: singers, composers, and choirmasters whose intricate vocal works transformed sacred music across Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. These were artists of great ambition and technical mastery, working under the generous patronage of the Dukes of Burgundy.

To modern ears, it may seem curious to elevate polyphonic music — simply, music with multiple independent vocal lines — as a revolutionary artistic development. But in the 1500s, the prevailing soundscape of church music was austere: Gregorian chant, sung in unison by a solo male voice. At the time, the Church and pious nobles preferred that form of singing because they believed that listeners would focus on the religious words and not be distracted from divine contemplation by harmonies or other embellishments.

The emergence of polyphony was not just a musical evolution, but a cultural shift, requiring greater artistic skill, larger ensembles, and, not least, patrons willing to support both.

The Dukes of Burgundy were just such patrons. Their wealth and territorial reach — from Picardy in northern France to parts of the modern Netherlands and Burgundy itself — enabled them to nurture a cultural ecosystem in which music, art, and literature could flourish.

Royal Library on the Mont des Arts

Philip the Bold (Philippe le Hardi), who ruled until 1404, was an avid book collector and laid the foundations for what would become the ducal library. He would eventually hand down the library to his heirs, including his grandson Philip the Good (Philippe Le Bon), who lived from 1396 to 1467. Over 300 of these manuscripts are in the Royal Library today.

Polyphony found perhaps its greatest champion in Margaret of Austria, daughter of Mary of Burgundy and Philip the Good. Born in Brussels, in the Coudenburg Palace, Margaret transformed her residence in Mechelen into a musical court of European stature. She directly employed composers such as Pierre de la Rue and took an active interest in preserving and expanding the family's rich trove of books and artworks.

Cultural melting pot

What later became Belgium was part of what was known as the Southern Netherlands, part of the Low Countries. The region later became part of the Spanish Netherlands when it came under the rule of the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714.

The area is known for its contribution to the visual arts, especially the Flemish Primitives and artists such as Jan van Eyck, who painted the Ghent Altarpiece which adorns the altarpiece in the city’s St Bavo’s cathedral, and Hans Memling, who lived in Bruges. The Chapel of Nassau, which is part of the museum in the Royal Library, contains two of the earliest copies of van Eyck’s Altarpiece.

One of the new exhibits in the museum gives visitors the chance to listen to a piece of polyphonic music written for Margaret. An array of sliders allows visitors to control the level of different male and female voices by fading them up and down. Doing this gives visitors a sense of how polyphonic music was composed and performed.

Royal Library on the Mont des Arts

The display traces five generations of Franco-Flemish polyphonists. Though many began their careers in the Low Countries, their reputations quickly spread to churches and courts in Italy and Germany. Manuscript copying helped disseminate their work throughout Europe, establishing the Franco-Flemish style as the dominant musical idiom of its time.

The journey begins with Guillaume Du Fay, who lived and worked at Cambrai Cathedral as well as in Bologna. Rome and Florence. The next generation is represented by Johannes Ockeghem, who was a vicar and singer at Antwerp’s Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe (Our Lady) cathedral. The third includes Jacob Obrecht, who died in Ferrara, Italy, after spending most of his career in Bruges and other parts of the Low Countries. From the fourth generation, Adriaan Willaert from west Flanders worked as a chapel master in Venice at St Mark’s Basilica. For the fifth, Orlandus Lassus started his career in Antwerp before moving to Munich in southern Germany where he worked in the court chapel of Duke Albrecht V.

The exhibits also showcase the work of Josquin des Prez, known as the “prince of polyphony” because manuscripts of his work were spread all over Europe. The first edition of his masses was the first printed music book dedicated to a single composer.

The renewed KBR exhibition brings all this vividly to life. With its focus on the Franco-Flemish polyphonists, it not only celebrates an essential chapter in Belgium’s cultural history but reaffirms the country’s historic place at the heart of Europe’s musical imagination. The museum’s holdings, including 80 exquisitely illuminated manuscripts from the 15th and 16th centuries, now resonate with sound as well as sight—allowing visitors to hear, quite literally, the voices of the past.