Any list of the greatest Belgians should include singer-songwriter Jacques Brel, the romantic post-war chanteur whose phenomenal passions were channelled into epic, melancholic odes about love, life and loss.

A few steps from the grave of painter Paul Gauguin in the Marquesas Islands of French Polynesia lies one of the greatest Belgians: Jacques Romain Georges Brel. The fact that the singer-songwriter-actor-director chose to be buried there sings volumes about his character.

He grew up in Brussels, raising a family in the city and spending half of his 49 years of life in Paris. Yet after his death in 1978, he was buried on Hiva Oa island in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean. Even more curious, a stele on his tombstone depicts him with a woman who was not his wife when he died.

In life, Brel was known for his emotional, evocative songs, infused with humour, honesty and heartfelt passion. Many fans assume he is French. To date, he is one of only three Belgians to sell more than 25 million records (after Salvatore Adamo and Frédéric François).

Brel was a crooner, a Belgian Frank Sinatra, known for his chanson songs typical of music halls or cabarets with an orchestra and poetic lyrics. “When you invent, you’re an aspirin,” he said in a television interview. “I continue to believe that if you can be an aspirin for others, and for the time of a song or a film, people don’t think about the problem that’s worried them all their life. Writing songs, singing them, acting or directly in films, all those things are aspirin jobs. They are a form of exhibitionism.”

In addition to being an artistic “exhibitionist,” Brel was an adventurer and thrill-seeker as a sailor who crossed several oceans and as a pilot who did aerobatics. He excelled at fulfilling his ambitions yet struggled to balance them against personal responsibilities. “I took care of my dreams,” he admitted. He admired the great explorers of the New World such as Vasco de Gama and Captain Cook. “My whole life has been a rollercoaster.”

Yet, while was extraordinary in his talent, Brel was ordinary in his humanity. He had flaws and foibles that hummed in the background as he sang.

The musician

While best known for his meaningful lyrics and passionate performances, Brel’s music was as important as his words according to his middle daughter France Brel. “To feed his soul and body, my father needed music. Since he was a teenager, he discovered that music was like a medicine for him,” she says.

Brel built up his musical knowledge mainly through classical composers like Beethoven, Chopin, Debussy and Ravel. His own music was a synthesis of them, which distinguishes him from other great “chanson” singer-songwriters, notes France.

“For example, his song Les Désespérés, is exactly like an excerpt from Ravel's music: very soft, without too many melodic lines,” says France, who is director of Éditions Jacques Brel, which oversees copyrights, and the Brel Foundation, which she founded in Brussels in 1981.

“One of his strengths was to marry the music and the words with his interpretation. For example, Les Marquises, which was one of his last songs, is very simple, but this simplicity is the result of great musical knowledge. And he does the same thing in his lyrics. They are simple, they speak of life, joy and sadness like Ne me quitte pas. It’s this simplicity that transmits something to others.”

While most of Brel’s songs were recorded in French, he also recorded some in Dutch. English translations of selected songs have been recorded by David Bowie, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, Barbara Streisand, Nina Simone, Olivia Newton-John, Sting and Celine Dion.

The Man

On and off stage, Brel was energetic, passionate, soulful, intense, kind, giving, humble and down-to-earth, France says. In interviews, his eyes sparkled with humanity. “For me, God is mankind and one day they will know it,” he said.

“My father had a lot of personality, but this was just one side of him,” France says. “The other side was his sensitivity, his observation, his fragility. Both sides are there in his songs.”

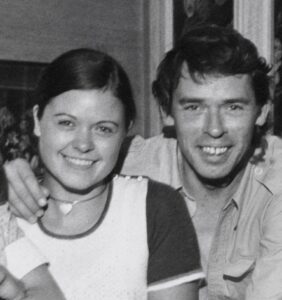

Brel with his daughter, France

Brel was also socially conscious and liked to help others. He was generous, giving a lot of money and gifts to many people, yet he was humble and discreet about it. “He never needed to be recognised as a generous person. At home, he never talked about his work or his recognition,” France says.

Her parents never talked about money or fame either. Social issues were their top topics. “My family had the characteristics of a simple life and what was important at home was friendship between people,” France notes. “It was ‘you have to help someone. You have to see someone who's sick’, but never success. I realised later that my father was very well known from newspapers. For him, being famous was not important.”

While Brel passed along these values, he did not spend much time with his daughters as a travelling troubadour. Indeed, he was mainly absent as a father. “He didn't play with us,” France says. “What was important is that his daughters were well behaved and nice. He showed us how he lived but he wasn't interested in what we did at all. When I saw him, it was a gift. For me, that was enough. I didn't need more. I didn't expect anything from my father. But that's not easy for other kids.”

Brel said, “Family is not enough.” France says that her father saw having a family as a job and that he needed several jobs and hobbies to be fulfilled, including writing, boating, flying and travelling.

One woman was not enough either. Brel had countless affairs, four of which lasted for years, during his marriage to Thérèse (‘Miche’) Michielsen. “It was a couple that started with friendship,” explains France. “Love is friendship, so they got married and they both wanted to respect each other and build a family like that. My mother agreed to give priority to my father and so he was very grateful to her.”

Her parents sometimes talked about divorce, but in the end, they never did. “She had patience and my father did not want to divorce a woman who was his friend and who did everything for his success,” France says.

Miche accepted that her relationship with her husband was largely contractual. She handled his administration and raised their three daughters while he built his international career and chased his dreams. But she was the only constant partner in his life, and he left his copyright and inheritance to her and his daughters. When Miche died in 2020, aged 93, France wrote that her father was “the diamond of her heart, the only poet of her entire life.”

Beginnings

Brel was born into a wealthy, bourgeois family in 1929 in Schaerbeek. His father, Romain, owned a corrugated cardboard factory called Vanneste et Brel with his brother-in-law in Anderlecht. Jacques' mother, Élisabeth (‘Lisette’), had a special bond with her son, who took after her generous, affable personality. His parents had him and his older brother Pierre late in life for their generation, especially Romain, who was age 46 when ‘Jacky’ was born.

Brel grew up in the Second World War, an adult world, missing out on his adolescence. He was 11 years old when the German army invaded Belgium in 1940. “People were prepared for dying instead of living,” he noted of that time. “I spent my adolescence practically alone without friends.”

He was not a good student, but he appreciated words, stories and poetry. Upon leaving school, Brel’s father found him work at his cardboard factory.

At the same time, Brel joined a philanthropic Catholic youth organisation in Brussels called La Franche Cordée, of which he became president in 1949. It inspired him to write and perform songs, which offset his boredom selling cardboard. La Franche Cordée also led him to his wife, Miche. They shared an interest in helping others and married in 1950 at ages 21 and 23, respectively. They had three daughters: Chantal, France and Isabelle.

Brel began performing his songs in cabarets, hospitals and lounges in Brussels – anywhere he could get gigs. He did not enjoy early success. At a song contest at the Knokke casino, he came in 27th out of 28. “When I started, I knew I was a star but no one else knew,” Brel said. He had no formal musical training other than some childhood piano lessons, and his songs were initially poorly written.

His first record, a 1953 single with the songs Il y a and La Foire, caught the attention of French talent scout Jack Cannetti, who encouraged him to move to Paris. As the Ancienne Belgique was the only major concert hall in Brussels at the time, Paris had much more to offer an aspiring talent. Brel wasn’t particularly fond of Brussels anyway. “For me, Brussels has always been a tram,” Brel said, and a place that was grey, rainy and where people never laughed. “I was affected by the colour of the sky.”

Fame

Brel said he was “scared of dying and getting too old too fast,” so he left for Paris in 1953, leaving Miche behind with their daughters. He began singing in the city’s cafés and small cabarets but failed to win over critics and audiences. For a while, he performed in seven cabarets a night just to pay for his food. “Earning only a few pennies by performing on the small stages of cabarets, my father was satisfied with one meal a day, and sometimes slept on benches and like a stranger in this big city,” says France.

The release of his first album, Jacques Brel et Ses Chansons failed to lead anywhere, but he found his first muse, French singer Suzanne Gabriello, who inspired him to write the love song that changed the course of his career. In 1957, he released his second album, Quand on a que l’Amour, with a song by the same title, which was a huge hit, won the Grand Prix de l'Académie Charles Cros, and secured a tour.

Even bigger successes came with his 1959 songs, La Valse à Mille Temps and his most enduring song, the pleading, desperate Ne me Quitte Pas. By the end of the decade, Brel was a star in France, known as ‘Grand Jacques,’ and headlining at the Olympia Theatre in Paris. His performing style – in a suit, on a bare stage – would involve energetic renditions that left him drenched in sweat.

In the 1960s, Brel had a new muse, Sylvie Rivet, the press officer of his record company, with whom he lived in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, on the Côte d'Azur. There he wrote songs such as Amsterdam, the grim anthem to the grimy Dutch port, his "sea-song which resembled a Bruegel painting,” as well as Mathilde and Les Bonbons. In 2008, Rivet’s heirs auctioned many objects from the house, such as a spiral notebook with the handwritten lyrics of Amsterdam, for a total of €1.27 million.

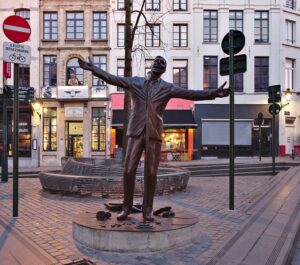

While Brel is undoubtedly one of Belgium’s favourite sons, he had a complicated relationship with his home country. He is adored in Brussels, where a metro station in Anderlecht was named after him in 1982, and a bronze statue of him was unveiled in 2017 at Place de la Vieille Halle aux Blés. But he enraged fans with his 1959 caricature Les Flamandes, a ribald song, supposedly about the Flemish and their terrible dancing. He denied accusations of misogyny – he was satirising the Church parochialism and Flemish right-wing conservatism – but made up for the offence with more affectionate paeans to Flanders, Le Plat Pays and Marieke.

The Brel statue in Brussels, entitled L'Envol

By 1966, Brel announced he would retire from performing and the next year, his last show was symbolically held at the Olympia. For the encore, Brel came back on stage, comically dressed in a nightgown. “It’s funny, nobody wanted me to start, and nobody wants me to stop!” Brel said. His final performance was followed by an album, Jacques Brel 67.

Brel then switched direction to cinema, beginning his movie career with Les Risques du métier. Around the same time, he translated and adapted Dale Wasserman’s stage musical The Man of La Mancha. He directed and played the lead in L’Homme de la Mancha in 1968-69 in Brussels then Paris. The off-Broadway revue Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris, which moved to Broadway in 1972 and was filmed in 1975, enhanced his profile across the Atlantic. Brel acted in 10 films from 1967 to 1973, two of which he directed.

Sailing, retreating

Around this time, one of Brel’s friends introduced him to sailing. On several voyages in the Mediterranean, he embraced his third long-time partner, Monique Galéanne (alias ‘Marianne’). He bought a 19m sailboat, the Askoy II, with the plan to sail around the world for three years. It was an act of escapism as he wanted to “take a step back, get away,” according to France.

Brel invited France, 21 at the time, to join him on his adventure. “I didn't know my dad much before,” she recalls, so she was delighted to change that and see him every day as opposed to just a few days a month. The other daughters did not go as Chantal was engaged and Isabelle was too young.

France and Jacques, 1975

While Brel had forewarned France there would be women on the boat and in ports from time to time, she was shocked to be greeted by a woman she did not know. This fourth and final long-term companion, Maddly Bamy, was a French-Guadalupian actress and dancer that Brel met in 1971 on the set of Claude Lelouch's film L'Aventure C'est l'Aventure. She was only supposed to stay on the yacht a few weeks. But she never left.

The three of them sailed in the summer of 1974 to the Isles of Scilly, the Azores and Madeira. But this idyllic existence was disrupted when Brel was diagnosed with tuberculosis and then lung cancer.

“To me, he was somebody always energetic, always in a good mood,” France says. “But on the boat, he was very sad. I had another man in front of me.”

France left but Brel took it badly. “I wrote to my father, but he never wrote back,” she recalls. “When he came back to Paris do some medical tests, I went to see him in the hospital, but he pretended to be asleep. He told others ‘France came to see me.’ So, he heard me. But he did not answer.”

Final days

In between his medical treatments, Brel and Bamy continued to cruise to the Canary Islands, Martinique in the Caribbean and eventually, all the way to the Marquesas Islands. “I am an adventurer, and it is in adventure and movement that I try to find my balance,” Brel wrote.

In autumn 1974, Brel had a tumour removed from a lung at the Edith Cavell Hospital in Brussels. To keep it out of the press, he was admitted under a false name to a maternity ward. He nonetheless became known to staff for wearing a red robe and eating two cakes a day as a pastry afficionado.

During hospital stays in Europe, Bamy and Miche competed for turns at Brel’s bedside. “My mother and sisters, and especially my mother, we knew that there were other women near my father, but we never saw them,” says France. “It was very discreet.”

Brel moved with Bamy to Hiva Oa in 1975, “where no one bothered him,” France says. There he wrote the songs for his final album, Les Marquises, which he recorded in Paris in 1977. He also fulfilled his dream of flying: Bamy had bought him a small plane, which he used to transport locals to and from Tahiti, a five-hour flight away.

In October 1978, Brel was hospitalised with pneumonia in Bobigny near Paris, unbeknownst to his family. He died of a pulmonary embolism at age 49 in Bamy’s arms. “Nobody told us he was in the hospital at my father's request,” France says, so they never got to say goodbye. But she did receive some closure in a letter that her father wrote to her before his lung operation, which she received from Hiva Oa after he died.

Brel asked to be buried on the island in Atuona cemetery facing the sea, to attract tourists to the island. “He wanted to help the Marquesans and make the Marquesas Islands a travel destination,” France says.

Legacy

France is clear about the distinction between Brel’s work and her personal memories. In 2018, she published two books about her father as author and singer, respectively, and last year she released ‘J’Arrive’, the first of three documentary films about her father’s private life, at the Brel Foundation. The next two will be released this summer and in 2023.

“There’s so much to say about my father,” she notes. She’s also writing a chronicle of his life: the first volume, about his childhood, will be published in May. “But I have to cover his whole life, so maybe I'll be writing for ten years,” she says. The foundation will also launch an online platform to show films about Brel like Les Adieux à l'Olympia.

Her work will help keep Brel in the public eye – although his legacy is strong enough to endure anyway, as he continues to inspire new generations of fans. As he said in a radio interview on New Year’s Day, 1968: “I wish you endless dreams and the furious desire to make a few come true.”

| The living tribute artists Jacques Brel had a mesmerising performing style, seemingly channelling his energy and emotion into his songs with a fervour that left him – and his audiences – drained. It has been widely imitated, but some cover artists have made a career performing Brel songs. Brussels-based Filip Jordens has been performing Brel’s repertoire for almost 30 years, mainly in Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Germany. He first heard Brel’s music when he was 12, playing a cassette his father owned over and over. He first performed Brel songs at age 17 in a high school talent contest for 500 Flemish students. Soon after he got a gig at a bar in Leuven, which expanded from eight to 24 songs. After Radio 1 in Brussels asked him to take part in a Brel tribute, aged just 21, he began touring with his Hommage à Brel. He has performed on behalf of the Belgian state on several occasions, such as King Philippe and Queen Mathilde’s 2018 visit to Canada. Jordens likens Brel to modern Belgian pop star Stromae due to his poetic lyrics and social commentary. “I remember seeing Brel for the first time on television when I was seven years old. I had never seen an adult being so authentic, real and honest,” he says. Paris-based aeronautical engineering graduate Arnaud ‘Askoy’ Bassecourt was a private detective in 2018 when he first heard Brel’s music and had an epiphany. He identified so much with Brel’s songs that he decided on the spot to take singing lessons and become a tribute act, which he considers “a great responsibility.” Like Brel, Bassecourt had a humble start, singing in the streets of Paris, then in bars and finally theatre. For Brel’s birthday on April 8, 2022, he performed his show La Promesse Brel during a dinner in celebration of the relaunch of Brel’s former yacht, the Askoy II, in Blankenberge, Belgium. The yacht was saved in New Zealand in 2008, brought back to Belgium and restored for the last 14 years by Staf and Piet Wittewrongel of Blankenberge. As of this May, Bassecourt will have regular gigs at the Eiffel Tower Theatre, followed by an autumn tour. In 2023, he hopes to follow in Brel’s footsteps at the Olympia Theatre in Paris. “He talks about friendship, love, separations, age, Belgium, Paris, everything,” Askoy says “And everything he says in his songs is still relevant.” |