On this day in 1815, the small suburb town of Waterloo on the outskirts of Brussels entered the history books in one of the most famous and bloodiest battles in European history.

The Battle of Waterloo culminated in the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte at the hands of an international alliance of British, Prussian and Dutch-Belgian armies.

And all began at a Brussels ball a few days before the big battle.

On the warm summer night of 15 June, the now infamous Duchess of Richmond’s ball was in full swing in the city centre of Brussels. The ball was taking place in a now-demolished townhouse owned by the Richmond family on 15 Rue de la Blanchisserie. All the senior figures of the Duke of Wellington’s British army, including the man himself, were present.

After much merriment, Highland dancing and elite courting amid members of the British colony stationed in Brussels, the festivities were abruptly cut short.

"The Duchess of Richmond's Ball", by Robert Hillingford, 1870s.

During the dinner, an officer approached the Duke of Wellington to inform him that Napoleon’s army had crossed the border into Belgium at Charleroi and was bound for Brussels. The mood quickly changed.

Wellington ordered his men at the ball to retreat from the evening, causing a dramatic scene as officers said their goodbyes before heading into the battle of a generation.

A few months earlier, the major European monarchies had declared Napoleon an outlaw after his escape from exile, agreeing to collectively mobilise 900,000 soldiers to launch an invasion of France – although they would not be ready until July.

With his fast descent towards Brussels, Napoleon had taken the Allies by surprise and was aiming to seize Brussels in a lightning victory over the British and Prussian troops stationed there. Napoleon hoped that a victory would dissuade the other Allies from daring to attack him.

The defence of Brussels

On 16 June, the day after the Duchess’ ball, hostilities began at the Battle of Quatre Bras, where British and French forces first clashed. The British held the farm and surrounding fields but were unable to join Prussian forces engaged at the larger Battle of Ligny.

Napoleon secured a strategic victory, setting up the final showdown to defend Brussels on 18 June.

Wellington decided it would be the small town of Waterloo, known for its elevated plains which could best serve a defensive position, to halt Napoleon’s march across Europe.

Wellington entrenched his troops at the Mont-Saint-Jean in Waterloo. Despite the numerical inferiority, he placed his army in a strategic position he knew well, with the promise of support from Prussian forces.

Napoleon prepares his Old Guard for the last grand attack at Waterloo, by Ernest Crofts (1905).

Meanwhile, Napoleon fancied his chances for victory, provided that he could keep the British-Dutch forces and the Prussians apart. In the early evening of 17 June, the French forces arrived at the outskirts of Mont-Saint-Jean, after a day's march.

After a 30 km march, Napoleon's men were tired, hungry, and morale was low. To make things worse, it had rained all day and would continue well into the night. Moreover, Napoleon was unaware that the Prussians were also marching towards Waterloo.

As the battle unfolded

At 11:30 on 18 June, Napoleon opened hostilities at Hougoumont farm. But the muddy conditions hindered the attacks against the British-Dutch forces and to make matters worse, Napoleon was suffering from bad health. The Emperor had to be taken off the battlefield for persistent stomach issues.

In the meantime, Wellington's troops put up fierce resistance – fighting off ten French charges by arranging themselves in squares in a defensive formation. But by late afternoon, Wellington's men struggled to contain the French onslaught.

The Battle of Waterloo, 1815 by William Sadler (1782–1839).

And then, in dramatic fashion, the Prussian troops led by Blücher finally arrived. Napoleon gambled his last chance by throwing his imperial guard into the fray. But the elite French soldiers were targeted from all sides and were finally forced into a panicked retreat.

The aftermath

Napoleon was defeated and Wellington and Blücher celebrated their victory at around 21:00 at the Belle Alliance farm that evening.

In total, the battle pitted nearly 300,000 men against each other, including 7-8,000 Belgians who fought on both sides – about 4,000 for France and a similar number for Dutch forces. The Belgian revolution would arrive 15 years later in 1830.

One of the bloodiest battles of this age, around 11,000 men were killed and 35,000 wounded, with nearly 4,000 dying shortly afterwards. Having lost many friends and comrades, Wellington's immortal words capture the sorrow of conflict: “Nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.”

Napoleon, defeated, returned to Paris where he abdicated before being exiled to the island of Saint Helena. He died almost six years later.

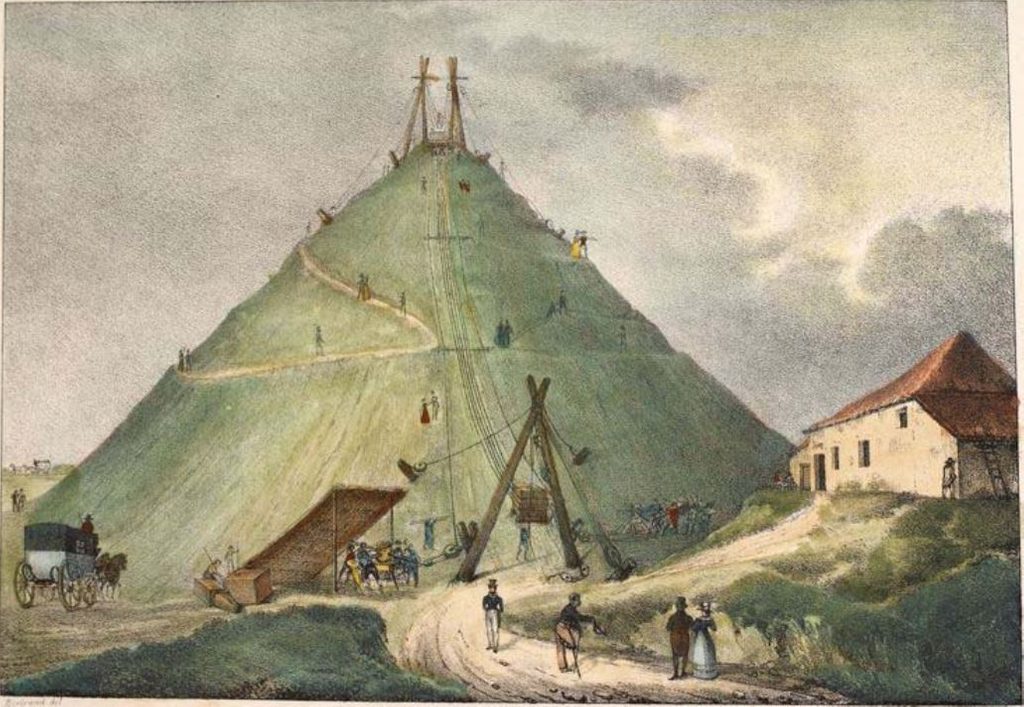

The erection of the Lion's Mound, 1825. Engraving by Jobard, after the Bertrand drawing.

In 1820, Dutch King William I constructed on the Waterloo battlefield the now famous Lion’s Mound at the spot where his son, Prince of Orange who was commanding the Dutch-Belgian troops under the Duke of Wellington’s orders, was wounded.

Wellington was not a fan of the monument's size and grandeur, supposedly saying, “They have altered my field of battle!”

"Today in History" is a historical series brought to you by The Brussels Times, aiming to take you on a trip down memory lane for newcomers and Belgians alike, written and compiled by Ugo Realfonzo & Maïthé Chini. With thanks to the Belga News Agency.