It was an especially brutal fortnight in an already savage conflict. In the village of Bourcy, near the Ardennes town of Bastogne, the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police, began searching homes. It was at the end of 1944, in the Battle of the Bulge, the counter-offensive by the German army against the advancing Allies.

In the cellar of the Roland family, the Gestapo uncovered an American flag, stitched together from pieces of dyed cloth to welcome the liberators in September. The Germans dragged Marcel Roland to an interrogation room in the village. “People heard the 47-year-old scream as the agents beat him up,” according to accounts. “Then the Gestapo took the Belgian outside again, his face bruised and his clothes bloody. They led him to a muddy area near the gendarmerie. There they finished their job, smashing the man’s skull with hammers and clubs.”

Elsewhere, a German officer gave his wife a grim assessment of the fight. “Always advancing and smashing everything,” he said. “The snow must turn red with American blood. Victory was never as close as it is now.”

In Bastogne, local 14-year-old Maria Gillet catches a glimpse of an American, brought in on a stretcher: “Where his legs have been,” she scribbles in her journal, “I can see only a shapeless mass of crushed flesh, blood spills onto the floor. My thoughts go to his faraway mother.”

The winter set freezing records and the soldiers barely endured. “It is so cold that every breath feels as if our lungs are full of ground glass,” a sergeant from Hoosick Falls, New York, observed when he arrived. An Alabama paratrooper in a foxhole found his morale tested to the limit. “I find myself thinking about my M1 rifle. A click of the safety and a tug of the trigger and my suffering could be over,” he admitted.

Repeated Allied bombardments of the enemy escape route through Houffalize left the town a moonscape of charred rubble. GIs kept their mouths covered to avoid inhaling the nauseating stench of burned flesh from German and Belgian corpses. “Strips of skin,” 19-year-old Private Mitchell Kaidy observed, “are left hanging from bare trees.”

Band of Brothers

These stories, collected by historian Peter Schrijvers in his book, Those Who Hold Bastogne, are testimony to one of the most vicious episodes of the Second World War, when the US soldiers held the line against Nazi counterattacks.

Now Bastogne has inaugurated a fourth standalone museum space, the Bastogne War Rooms, dedicated to the Battle of the Bulge, which marks its 80th anniversary later this year.

That many museums dedicated to one subject might seem excessive for a town of 40,000. Yet over 150,000 visitors, half of them foreigners, come to Bastogne every year to experience the history of the pivotal battle.

Why is the battle such an intensely emotional touchstone, especially for Americans for whom it is a vivid memory?

First, it was the largest and bloodiest single battle fought by the United States in the Second World War and the third-deadliest campaign in American history.

Bastogne's Place du Carré, now Place du McAuliffe, after the battle

Second, it was also one of the most decisive battles of the war, as the last major offensive attempted by the Axis powers on the Western front. After this defeat, Nazi forces had no option but to retreat for the rest of the war.

Third, although the exceptionally cold weather and massive cloud cover marked a nadir for the surrounded Allied forces on Christmas, they stood firm, as symbolised by General McAuliffe’s almost mythical one-word message rejecting the German ultimatum to surrender: “Nuts!”

US tank

And finally, more than half a century after the battle, as those personally involved in the events began to leave the scene, a whole new generation discovered the story thanks to historian Stephen E. Ambrose’s oral history project, Band of Brothers.

Ambrose interviewed veterans from Easy Company in the 101st Airborne Division, and his book was then turned into a TV miniseries by Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg. The realism of the series and the intimate scale of the relationships of the characters made for riveting viewing. It won seven Emmys, including Outstanding Miniseries, became one of the bestselling TV DVD sets, and is regarded as one of the finest TV series ever made.

Breaking point

The Battle of the Bulge, from December 16, 1944 to January 25, 1945, was essentially a German effort to split the Allied lines, allowing them to individually encircle and destroy the four Allied armies.

Adolf Hitler planned to pierce the thinly held lines of the US First Army and by the end of the first day get the armour through the Ardennes; then by the end of the second day, reach the Meuse between Liège and Dinant; by the third day seize Antwerp; and by the fourth day take the western bank of the Scheldt estuary. However, Allied resistance put paid to that Blitzkrieg scenario.

More than one million soldiers took part in the campaign. The Germans committed over 410,000 men, 1,400 tanks and armoured fighting vehicles, 2,600 artillery pieces, and over 1,000 combat aircraft. They suffered between 60,000 and 105,000 casualties and depleted their armoured forces, which remained largely un-replaced throughout the remainder of the war.

Allied forces eventually came to more than 700,000 men – 600,000 American and 100,000 British and Canadians – with over 80,000 casualties. In the Bastogne area alone, 25,000 German lives and 23,000 American lives were lost. Civilian deaths were less well tabulated but 3,000 local Belgians are thought to have died.

The counter-offensive also had an impact far beyond Bastogne: 10 hours into the assault, one of the German V-2 rockets destroyed the Ciné Rex in Antwerp, killing 567 moviegoers, the highest death toll from a single rocket during the entire war.

Guts and nuts

The cold made the battle exceptionally harsh. On December 21, the temperature dropped precipitously and because of the cloud cover, the planes couldn’t take off and drop supplies to the encircled Allied troops. No food, no proper cold weather gear, no supplies of any kind. The troops on the ground had to hold the line in the woods, in the fields, day and night, by temperatures that fell to 15 C° to 20 C° below zero.

US soldiers would have to defend in temperatures of up to 20° below zero

In some American units, more lives were lost and more were wounded by the weather than from German bullets. For instance, they were living in their foxholes which, when dug, were frozen but because of body heat the ground around them would start to defrost. Soon their feet were in a pool of icy water, and with no change of socks they faced the real risk of trench foot and even amputation.

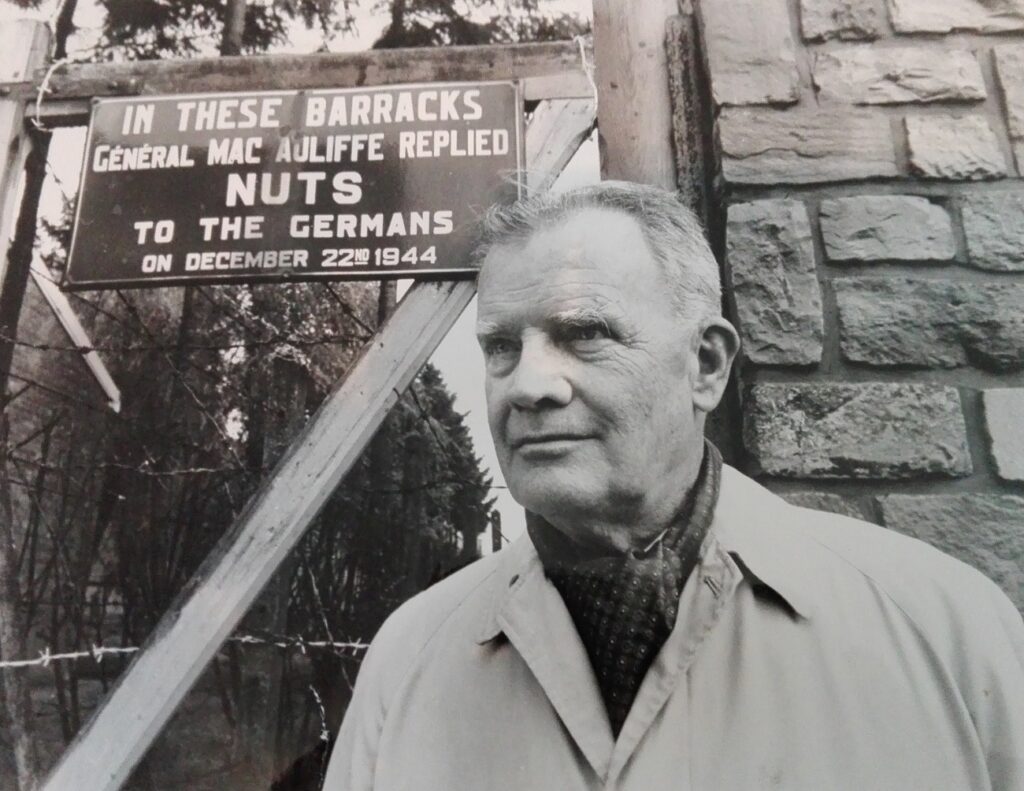

On December 22 the Germans issued their ultimatum, famously answered by General McAuliffe’s defiant reply, “Nuts!” However, the troops weren’t aware of this exchange until Colonel Kinnard’s Christmas Day message which was signed by McAuliffe and sent to all the troops defending the Bastogne perimeter.

General McAuliffe would return to Bastogne, where he was still remembered

“Merry Christmas,” Kinnard wrote. “What is merry about this, you ask? I will tell you, we stopped the entire German offensive, coming from the north, from the south, from the east, from the west. We are still keeping and holding the town of Bastogne and holding the perimeters. So, we can be proud of us.”

The nuts episode boosted morale for the troops that were resisting in very dire conditions, besieged on all sides by the German Army, the Luftwaffe and the weather.

Assorted attractions

Bastogne has developed an array of attractions to commemorate the battle. There is the Bastogne Barracks which consists of 2,350 square metres of indoor hangar space and additional exterior space filled with numerous Second World War track and wheel vehicles, artillery pieces and assorted equipment, both from the Allied and Axis Forces.

The 101st Airborne Museum situated in an old army mess hall immerses the visitor in the history and mystique of the fabled company, whose exploits were exhaustively detailed in Band of Brothers.

The newly-opened Bastogne war rooms

And the Bastogne War Museum, opened in 2014 for the 70th anniversary, presents four distinct experiences: there is the museum proper which displays hundreds of objects and offers interactive terminals; Generations 45, which follows the lives of an American veteran and a German veteran through European history from 1945 to 1989; and a visit to the remnants of the Bois Jacques battlefield with an augmented reality mobile application to transport the visitor back to the battle. The Bois Jacques also overlooks the village of Foy which the Americans needed to take and the Germans needed to keep, so the battle here was especially bloody.

And fourth, we now have the Bastogne War Rooms, which is in the actual location of the American headquarters in 1944. The barracks were built in the 1930s by the Belgian army, before being occupied from 1940 to 1944 by the German army, and then taken over by the American troops who liberated the region in September 1944.

Why we fight

During the Battle of the Bulge and the Siege of Bastogne, the American command ran operations from the cellars to protect themselves because of the constant shelling by the German artillery as well as bombing by the Luftwaffe.

The Bastogne War Rooms uses immersive scenography techniques and actual historic objects to plunge visitors into a reconstruction of the pivotal moments that occurred at this site, including the Nuts scene.

Mathieu Billa, the manager of the Bastogne War Museum, explained that one of the challenges in setting it up was gathering the facts. “For instance, in the village where I grew up, I was told of events such as a hand-to-hand combat in the village that resulted in 20 German deaths,” he said. “In my research, I never came across any mention of this incident. But now I have those witness accounts and the archived writings of the village priest.”

The 101th airborne company near Marvie

There are also aerial photographs in the exhibit that were taken by a pilot on board a P-28 Lightning which was shot down. Months later, two young brothers found the wreckage and the camera. One of them, still alive at 92, contributed his recollections and photos to the museum display.

But the major emotional punch of the museum is the cellar, which exudes an eerie and claustrophobic atmosphere. Augmented by four brief immersive videos, the raw, forbidding space highlights how the Allied headquarters were in a figurative rat hole – and drive home what courage it took to keep resisting.

The challenge for the US Army was to cut through the enemy line and take as many prisoners as possible. However, the Germans, retreating from Russia for two years at this point, were very experienced in defensive warfare and continued to inflict major losses on the Americans. General George Patton wrote in his diaries on January 4: “We suffered substantial losses today. The Germans are formidable fighters. Sometimes they cause me to be sceptical on how this is going to end. We can still lose this war.”

Then there are objects that when touched, tell you a story. There’s an American parachute turned into a dress sewn with intricate stitching by a local woman and her daughters. Or a helmet, one of many clothes and pieces of equipment recuperated from the battlefields by locals as they rebuilt their community from the utter devastation. The helmets were used for years to feed farm animals: chickens and the cows had American helmets but only pigs were fed from German ones.