Over 100 years after he won the Victoria Cross for his exploits at the Battle of the Somme, the legendary Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart, often labelled as Britain’s greatest ever soldier, is being honoured by his compatriots – in Belgium.

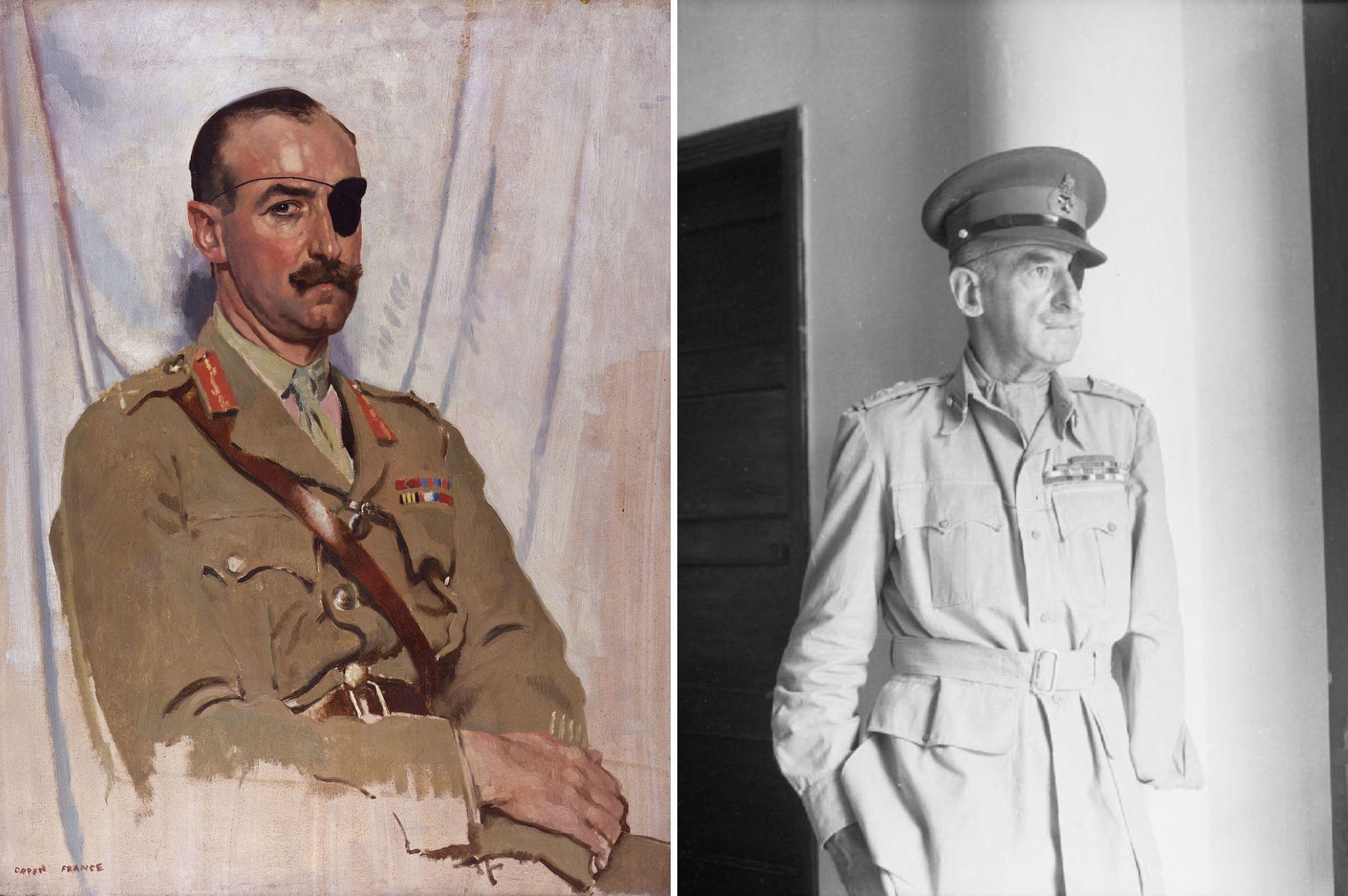

Described by Winston Churchill as “a model of chivalry and honour”, the one-eyed, one-armed, 11-times wounded indestructible hero is famed for going over the top in the First World War’s bloodiest clash while armed only with a walking stick.

His citation for Britain’s highest military decoration praised the acting lieutenant colonel’s “dauntless courage and inspiring example” as he led the 8th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment “unflinchingly through fire barrage of the most intense nature” on 3 July 1916.

A bronze plaque recalling his award, one of 11 inscribed with the names of overseas Victoria Cross winners, was presented to Belgium in December 2014 to mark the centenary of the war. Incredibly, it has been kept since then in storage at the War Heritage Institute in Brussels.

The plaque for Adrian Carton de Wiart will be unveiled in May 2025.

However relatives of Carton de Wiart have now succeeded in ensuring that Carton de Wiart’s exploits will be properly honoured in his home country, with the plaque due to be officially unveiled on 22 May at the city’s prestigious Prince Albert Club.

Baron Christian Houtart, related by marriage to Carton de Wiart, said: “His memorial deserves a more fitting place than a cellar. It wasn’t even a wine cellar!”

Pulled off his own fingers

Born in Brussels and reputedly an illegitimate son of King Leopold II, Carton de Wiart was sent to boarding school in Britain for his education. His extraordinary Army career began at the dawn of the 20th century in the Second Boer War, when he enlisted as a trooper in the 9th Battalion Imperial Yeomanry – after lying about his age and nationality. Soon after arriving in South Africa, he sustained the first of his many wounds after being shot by a sniper.

He was invalided out of the Army but, after quitting his law studies at Balliol College, Oxford, paid his own way to return to South Africa, where he joined another cavalry unit and was wounded again. By the start of the First World War, he was serving with the Camel Corps in Somaliland. During an attack on a dervish stronghold at Shimber Berris, he was shot in the face, losing his left eye and part of his ear. His bravery earned him the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

Carton de Wiart convinced a medical board that he was fit for service on the Western Front after wearing an uncomfortable glass eye, which he promptly discarded for his trademark, piratical black patch. In the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, he was shot in his left hand and pulled off his own fingers when a doctor refused to amputate.

The hand could not be saved and he returned to action the following Spring with the ‘Preston Pals’. He took command of the 8th ‘Glosters’ a fortnight before the Battle of the Somme, where he tenaciously held the village of La Boiselle in fierce fighting after three other commanding officers were killed.

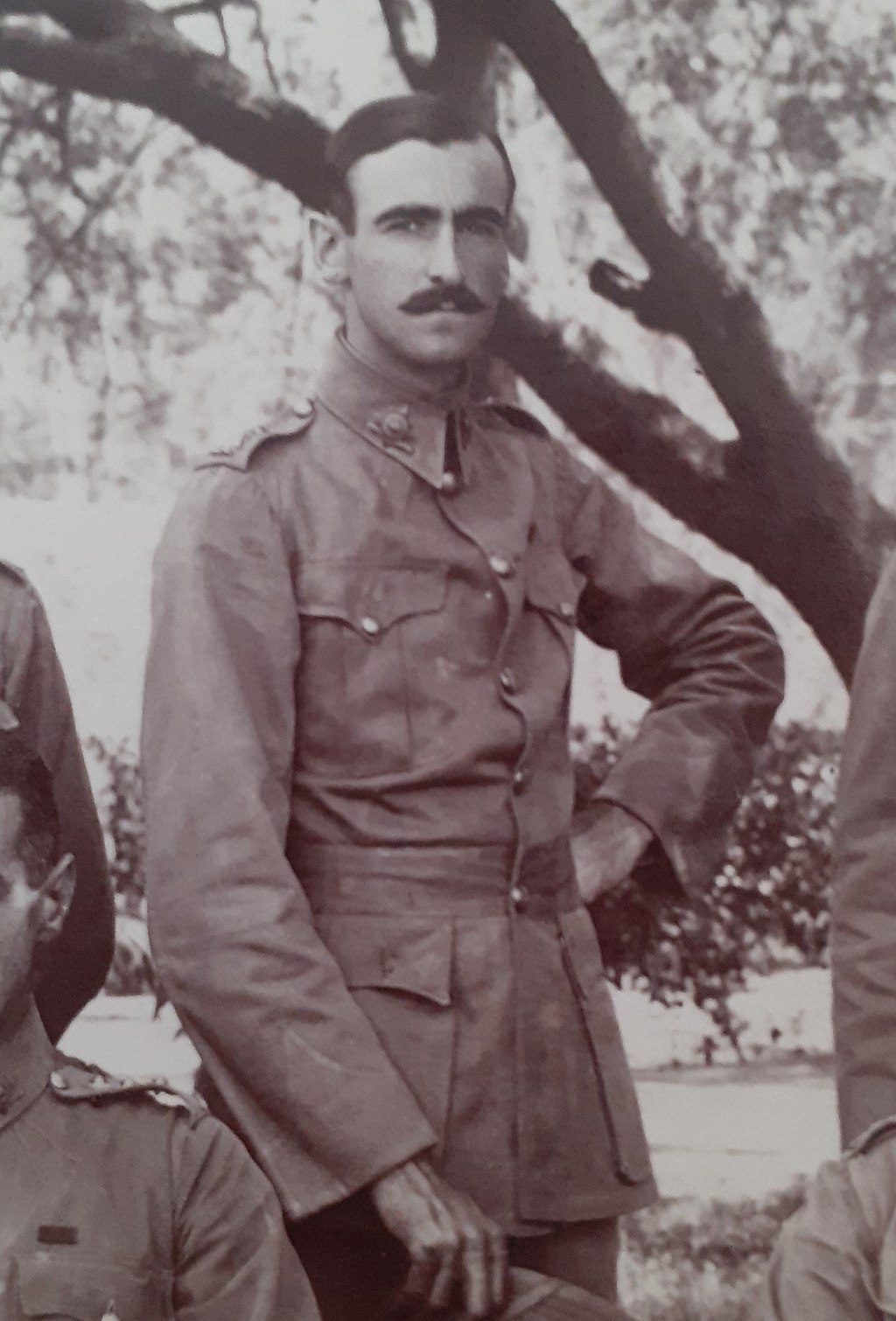

Carton de Wiart as a lieutenant with the 4th Dragoon Guards at Muttra in September 1904

Days later he was wounded yet again at High Wood when a bullet went through the back of his head. In his rollicking 1950 autobiography, Happy Odyssey, Carton de Wiart recounts that, as a result, his “neck tickled” whenever he had a haircut afterwards. Ever self-deprecating, he makes no mention in his book of his VC, presented to him by King George V.

After rapid promotion from Captain to Brigadier in a year, he saw action at the Battle of Arras and the Third Battle of Ypres – Passchendaele – where he was wounded in the hip by a shell. After treatment in London, he commanded the 105th Brigade, only to be wounded again, this time in his leg. After another spell in hospital, he returned to France before the Armistice. Describing his experiences, he declared: “Frankly, I had enjoyed the war.”

He went on to head the British Military Mission in Poland and, after resigning his commission in 1923, stayed there for the next 15 years, living in a remote lodge in the Pripet Marshes, a huge wetland close to the Russian border, where he could pursue his passion for hunting every day. He was recalled to his former post in 1939 and was lucky to escape when the German invasion triggered the Second World War.

Promoted to acting Major General, Carton de Wiart commanded the ill-fated expeditionary force at Namsos in Norway, where he demonstrated his typical sang-froid during incessant Luftwaffe attacks before the troops were evacuated by a naval force led by Lord Louis Mountbatten. Appointed in April 1941 to head a British mission in Yugoslavia, he was en-route between Belgrade and Cairo when his plane developed engine trouble and came down off the coast of Libya. Carton de Wiart, then 62, swam half a mile to shore – only to be captured by Italian forces.

After four months in captivity at the Villa Orsini in Sulmona, he was transferred to a prison for senior officers at Castello di Vincigliata, a medieval Tuscan fortress. He thought only of escape and kept in shape with a rigorous daily exercise regime. After initial attempts were foiled, Carton de Wiart and several comrades tunnelled out to freedom in March 1943. Despite his distinctive appearance, he was on the run for eight days, covering 150 miles, before being captured near Bologna with Lieutenant General Richard O’Connor, who would later command VIII Corps during the Normandy campaign.

Released in August 1943 after the Italians asked for his help in armistice negotiations with the Allies, Carton de Wiart was appointed by Churchill as his personal representative to the Chinese leader, Chiang Kai-shek. He fell in love with the country and Churchill’s successor, Clement Atlee, asked him to stay on in the job after the war ended.

British soldiers on the quay at Namsos awaiting evacuation from Norway. On the left is Major General Carton de Wiart.

Despite all his escapes on the battlefield, Carton de Wiart’s luck finally ran out when he broke his back after slipping on a staircase at a friend’s house in Rangoon, Burma. Said to be the model for Evelyn Waugh’s fire-eating Brigadier Ben Ritchie-Hook in his Sword of Honour trilogy, he officially retired from the British Army in October 1947.

In 1951, at the age of 71, he married Joan Sutherland, a divorcee 23 years his junior who had helped nurse him in hospital. His estranged first wife, Austrian Countess Friederike Fugger von Babenhausen, had died in 1949. Neither she, nor their daughters Anita and Maria, are mentioned in his best-selling autobiography. With the proceeds, he bought Aghinagh House, a former church rectory on the River Lee at Killinardrish in County Cork, where he and Joan enjoyed the outdoor, country life.

'Strong accent'

Speaking this week, ninety-five-year-old Baron Christian Houtart recalled his vivid memories of his ‘uncle Adrian’, his mother’s cousin. He first met him in 1939 when Carton de Wiart was passing through Belgium on a return trip to Poland. “He spoke French with a very strong British accent,” he laughs.

Carton de Wiart regularly visited his old homeland in retirement. As a young officer in the Belgian cavalry, Houtart remembers how he took his illustrious relation on a week-long trip around the First World War battlefields in 1955. “I had the privilege of driving him, in my first Citroën 2CV, from Peronne to Thiepval in France, then to Dixmude, Nieuport and Passchendaele. Places he remembered very well.”

Belgian soldiers training in Tenby

Houtart, chairman of the Tenby Memorial Committee which commemorates the creation of the Free Belgian Forces in Wales in 1940, concludes: “He remained very alert for his age, was always very personable and very neat in the way he dressed. He did not seek to impress people and knew how to handle humour, turning things toward himself and not others. Despite his numerous war injuries, he loved hunting with his modified rifle and always enjoyed his rather sporty cars.”

Carton de Wiart died in his sleep, aged 83, on 5 June 1963. Lady Carton de Wiart never remarried and passed away at Killinardrish in January 2006, aged 102.

Ellen Lefèvre, head of administration of the War Heritage Institute in Brussels, denied that the Carton de Wiart plaque had been kept in a cellar, but was rather in a “tunnel used for storage” because it was impossible to exhibit everything. The plaque was being given to the Prince Albert Club on a long-term loan, she added.