Suspects in terrorism-related cases in Belgium are younger than ever, according to the Federal Public Prosecutor's Office's annual report for 2024 that was released on Monday.

The Belgian authorities recorded an exponential increase in the number of cases "involving minors suspected of acts qualifying as terrorism": while 16 cases were opened in 2022, that number rose to 24 in 2023, and in 2024 it more than doubled, to a total of 55 cases in total.

"It mainly concerns younger people who are 15, 16, or 17 years old. But over the previous years, we noticed that these minors are becoming even younger," Kevin Volon, spokesperson for Belgium's Coordination Unit for Threat Analysis (CUTA), told The Brussels Times.

Of the 380 people on CUTA's endogenous threat database, just under 20 of them are minors – meaning it remains relatively limited. Similar figures were published in the annual intelligence report by Belgium's State Security (VSSE) as well.

"In terms of radicalisation, they are also becoming increasingly active on social media, including with calls to proceed to action or express specific threats," he said. "That is certainly a trend that we remain vigilant for."

'Salad bar ideology'

These radicalised minors on CUTA's watchlist are spread all over Belgium. "This is the case for all ideologies. It mainly concerns jihadism (around three-quarters of cases), but we also see a reasonably significant influence of extremist far-right narratives among minors. There are hardly any cases of left-wing extremism among minors."

CUTA found that some minors are often particularly attracted to violence, but do not always have a clear vision or narrative yet. "We see that they want to commit some form of violence towards society, or specific people or things. Only then do they try to attach a narrative to their interest in violence."

Referring to this phenomenon as the "salad bar ideology," Volon explained that this occurs when people pick and choose pieces of information from different narratives – which overlap, converge, but sometimes also contradict each other – to inform their extremist belief system. "They are not always coherent in their ideological vision, but are looking for a reason to commit an act of violence."

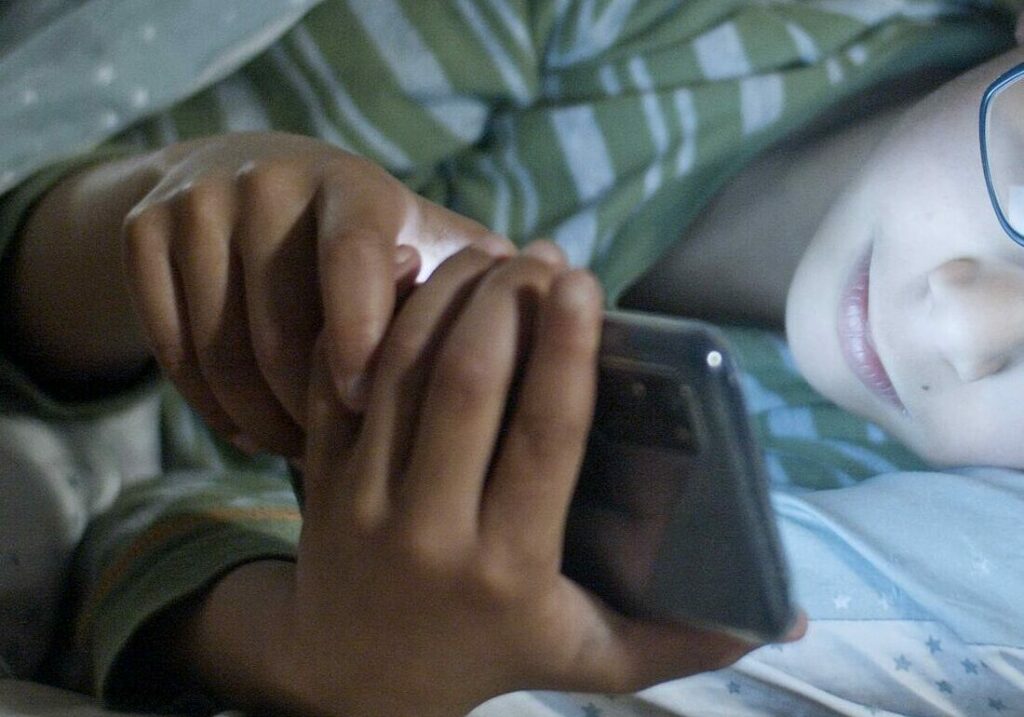

"Additionally, these minors are super active on social media, for all types of ideologies. This way, propaganda spreads much more easily to and among underage people," he said.

Credit: Moritz Kindler/Unsplash

At the same time, terrorism has always been primarily an issue of the youth, according to Thomas Renard, Director of the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism and Senior Associate Fellow at the Egmont Institute in Brussels.

"Historically, young people have always got involved in terrorist activities. There are always exceptions, of course, but the average age of the people arrested and convicted for terrorism has always been in the early in their early to late 20s," he told The Brussels Times.

This happens, he said, because young people are more easily ideologically radicalised, and more easily persuaded to pursue their ideals through violence as well. "Youth correlates with more risk factors: lack of critical thinking, intense emotions, a lack of filters, a lack of self-control, and sometimes a lack of empathy. These factors facilitate a binary vision of the world."

Spending life online

"What is new here, however, is that it now concerns very young people. Children as young as 12, 13, 14 years old are getting involved in these activities," Renard said.

While he pointed out that blaming social media for young people's (very) early radicalisation is too simplistic, he also stressed that the internet is the key difference between this generation and all the previous ones.

"If you look at all the ongoing terrorist investigations into minors, what they have in common is very young individuals who were radicalised online through their interactions with different social media groups," Renard explained.

Credit: Belga

Some of these groups are open, others are closed. Sometimes, small cells of individuals are arrested, others have never met in real life. "This also happens with adults nowadays, because that is the new configuration of our lives. We spend a good amount of our time online."

In the 2000s and even 2010s, people could still radicalise at a young age, but it was much harder to do that in complete isolation. "Friends, family, acquaintances... There would be signals," Renard said.

The key difference is that now, young people have access to these ideologies "without a filter, without intermediaries, and can act upon these ideologies on their own, without teachers, friends or family noticing, oftentimes," he said. "Most of it happens behind a screen in a closed bedroom. As a result, a very quick drift can occur without many people noticing. Until it is too late."

Know your customer?

On top of the easy access, Renard pointed out that several terrorist groups and organisations – including the ISKP, in particular – have developed propaganda that is inspired by the communication codes of younger people, and therefore appeals to a (sometimes very) young audience.

"They use gaming language or visuals, and many other gamification principles – such as giving people small missions, for example," he explained. "They do that, knowing that a good chunk of their audience is made up of young people. They might not necessarily be aiming for minors per se, but they are using the new codes of communication – just like a good marketing expert would do for a general social media ad nowadays."

By moving almost exclusively to online spaces, the geographical dimension became less important and has made room for a linguistic dimension. "While there used to be so-called radicalisation 'hubs' in Brussels and Antwerp, for example, this is now much less the case. It is no longer about where you live, but about the language you interact in."

In Belgium, this means that Dutch-speaking internet users will be much more likely to interact with people in the Netherlands, while French-speaking Belgians will interact a lot with people in France or Switzerland, or even Africa. "As a result, this makes these networks harder to track down and dismantle."