Each year on 21 July, Belgium marks its national day. Far from a celebration of Belgian unity, it marks the day when, nearly 200 years ago, Belgium’s first king took his oath as the newly formed country’s first monarch. But to understand the birth of Belgium, we must go back even further, to a time shaped by subjugation, turmoil and revolution.

Much like its neighbour to the west, Belgium’s modern existence was born following a bloody revolution, which toppled decades of foreign monarchist rule. After the defeat of Napoleon at the infamous battle of Waterloo, a meeting of the leading powers of 19th century Europe came together to redraw the map of Europe, seeking to redraw the map and usher in a new period of stability on the European continent.

The nations around the table in Vienna, Austria, represented by Britain, Prussia, Bourbon France, Russia, Sweden, Austria and Spain brought an end to the French occupation of what is now modern-day Belgium. The Southern Netherlands, as it was called then, had been passed between several European empires, including the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs, before being incorporated into France in 1795.

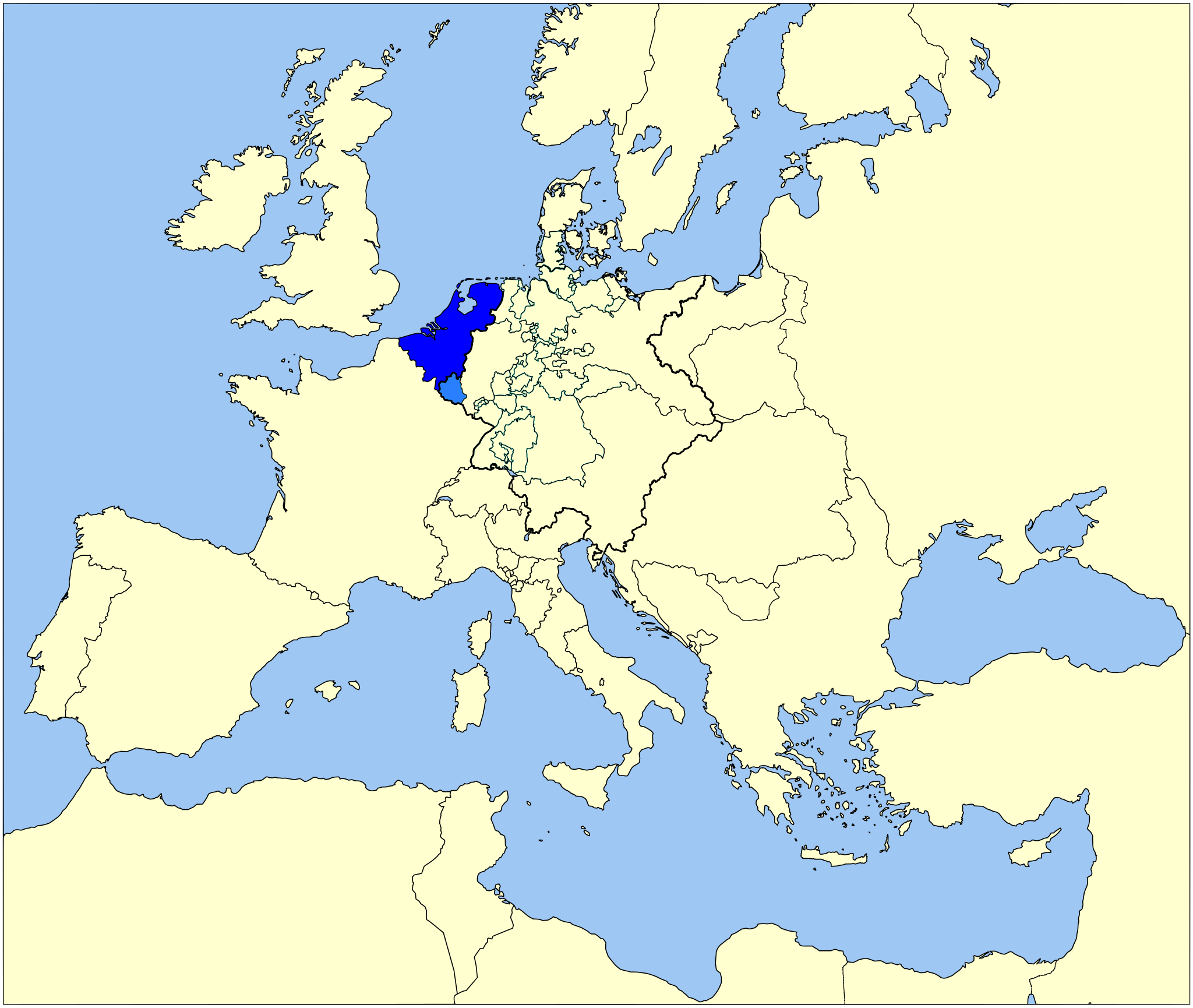

The European powers decided to merge the largely Protestant Dutch-speaking north with the Catholic French- and Dutch-speaking south, now controlled mainly by Belgium. The goal was to create a buffer state between France and the rest of Europe, and King William I of the House of Orange was placed in charge of the newly formed United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands, as it existed in 1815, encompassed all of modern-day Belgium. While the south was largely Catholic, the north was staunchly Protestant. Credit: Sir_Iain, 52_Pickup/Wikimedia Commons

As with many of the attempts of European powers to redraw the political map of Europe, the decision to join much of the proudly Catholic Flanders and Wallonia to the staunchly Protestant North was deeply unpopular. At the time, the Southern Netherlands had a much greater population and had a thriving economy, which envied that of the North.

Belgians felt underrepresented in the national politics of the Unified Dutch Kingdom and sidelined in the military and public administration. Tensions rose further when King William introduced Dutch as the sole official language in Flanders, alienating both French-speaking elites and many Flemish speakers. Southern Catholics also resisted the King’s attempts to control church education and appointments.

Unlike the modern-day, the Southern Netherlands were particularly prosperous compared to the rest of the Netherlands, and southern industrialists resented Dutch control over trade and the national debt, most of which had been accrued in the north. In the 1820s, an uneasy alliance of opposition movements grew among both Catholic and liberal circles, giving rise to what became known as "unionism", a tactical alliance between ideological rivals who shared a desire for greater Belgian autonomy.

Tinderbox in Brussels

Tensions grew throughout the 1820s. All that was missing was the spark. This final trigger came from abroad. In July 1830, the revolution in France toppled Charles X and installed a constitutional monarchy. The events in Paris emboldened revolutionaries of many different ideologies across Europe and heightened tensions in the Southern Netherlands. That summer, poor harvests and rising unemployment further fuelled public discontent.

Much of Belgium's modern history can be traced back to Belgium's Royal Theatre of La Monnaie, the scene of the start of the Belgian revolution. Credit: Edison McCullen/Wikimedia Commons

On 25 August, during a special performance of the opera La Muette de Portici at the Royal Theatre of La Monnaie in Brussels, a group of spectators joined demonstrators in the streets. That night, riots broke out. Crowds smashed up industrial machinery, looted businesses and chanted patriotic slogans inspired by the performance. Revolution swept the city, and some of Brussels’ disenfranchised elites joined the protestors. Attempts to contain the uprising quickly failed.

In the days that followed, Crown Prince William, the King's eldest son, arrived in Brussels to assess the situation. He met with local leaders and expressed openness to granting Belgium administrative autonomy. His proposals were sent to The Hague, but the King refused to entertain them. Viewing the unrest as rebellion, he chose instead to deploy military force.

Armed resistance and independence

On 23 September, Dutch troops led by Prince Frederik entered Brussels, the future Belgian capital. What followed was a bloody three-day battle in the streets around the royal park and palace. Despite being less well-armed, the citizen militias and revolutionary volunteers, some coming from abroad, managed to hold their ground. By 26 September, the Dutch were unable to deliver a swift victory and withdrew from the capital.

A revolutionary scene on Brussels' Grand Place depicted by Égide Charles Gustave Wappers.

This military retreat marked a turning point. A group of revolutionary leaders, including Charles Rogier, Félix de Mérode and Emmanuel van der Linden d’Hooghvorst, many of whom are honoured with street names across the city today, formed a Provisional Government. On 4 October, they issued a declaration proclaiming Belgium’s independence. Elections followed within weeks, with 30,000 eligible electors, mostly landed citizens, casting their votes, and a National Congress convened in November to draft a constitution.

Finalised in February 1831, the charter established a constitutional monarchy with civil liberties and a separation of powers. Although voting rights remained limited to property-owning men, the constitution was among the most liberal in Europe at the time.

The search for a King

The formation of a new European state was both a blessing and a nightmare for the political powers of Europe. The Netherlands was outraged and opposed to any recognition of the new Belgian state. The British, the dominant power on the European continent, were keen to establish a stable buffer state to separate the continental powers.

The Dutch appealed to nations such as Russia and Austria, both troubled by succession movements, to help them put an end to the Belgian state, but received no tacit help to achieve this.

A key step in the recognition of the new Belgian state would be the selection of an appropriate monarch. This was a delicate task. Belgium sought to appease the monarchist powers around its borders. Selecting a leader from the wrong royal family could cause decades of tension with its new neighbours, or even spell its demise.

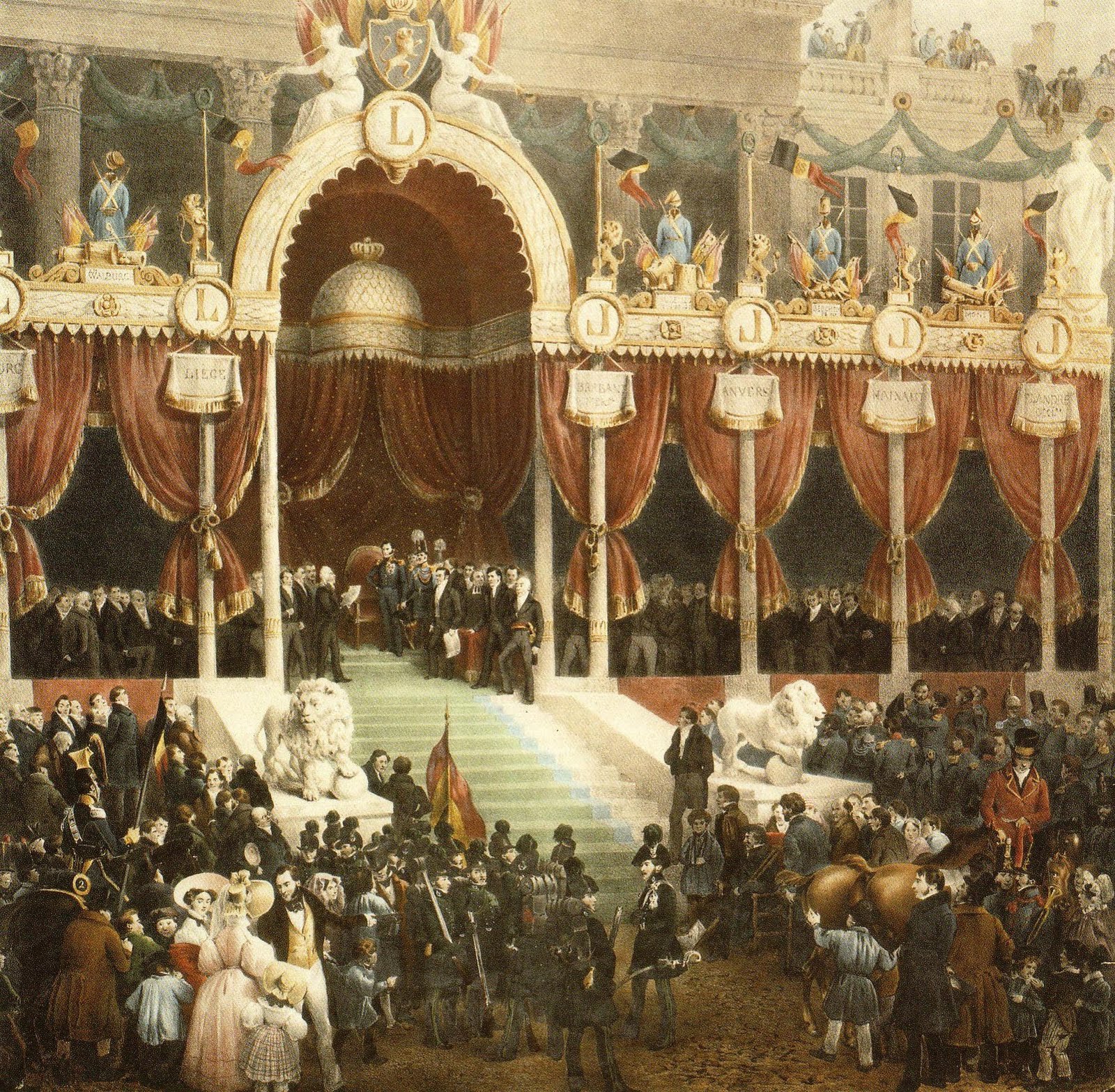

Leopold taking the constitutional oath during his enthronement, as depicted by Égide Charles Gustave Wappers.

The initial choice, the Duke of Nemours, son of France’s King Louis-Philippe, was squarely rejected due to British concerns about growing French influence, especially in the aftermath of Napoleon’s grip on Europe. The Congress eventually turned to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, a German nobleman with ties to the British royal family, who later married into the French royal family. Leopold I accepted the offer and was sworn in on 21 July 1831.

This tactical decision satisfied both the French and British, protecting the new and vulnerable state. But for King William, the coronation was an outrage. Within weeks of Leopold’s ascension, Dutch forces launched a new invasion in what became known as the "Ten Days’ Campaign."

Belgian troops were pushed back in several battles, and the young kingdom appeared to be at risk. However, under a previous international understanding, France sent troops to support the Belgian side and preserve the new buffer state. The Dutch withdrew in the face of French reinforcements, and an uneasy ceasefire was declared.

Diplomacy and recognition

Despite the battle for Belgium, the future of the nation was decided not on the battlefield, but on the negotiation table in London. The European powers met to discuss the Belgian situation. After months of negotiation, the powers agreed that Belgium could become an independent and neutral state.

A preliminary settlement, the Treaty of the Twenty-Four Articles, was drawn up in October 1831. It confirmed Belgium’s independence but required territorial concessions to the Netherlands, particularly in Luxembourg and eastern Limburg.

Although Belgium’s leaders reluctantly accepted the terms, King William I refused to sign. It was not until April 1839, nearly nine years after the uprising, that the Dutch finally recognised Belgian independence through the Treaty of London. Despite the fact that cities such as Maastricht, Roermond, Venlo, and Weert also rose up against Dutch rule, these territories were ceded back to the Netherlands. Belgian revolutionaries were forced to flee or were stripped of their influence upon the territories' return to the more conservative Dutch state.

Luxembourg also rose up and attempted to join Belgium, flying the tricolour. However, due to the presence of a strong Prussian garrison, it ultimately was not able to join the Belgian state. Under the Treaty of London, parts of Luxembourg ultimately joined Belgium, while the rest remained part of the Grand-Duchy, which was at the time aligned with the Dutch.

One of the most significant results of the Treaty of London was the declaration of Belgian neutrality and a pledge to support the independence of Belgium. This status, however, gained a nickname as a “scrap of paper” by the Germans, who invaded in 1914, prompting Britain’s declaration of war on Imperial Germany.

A truly Belgian revolution

While the formation of the Belgian state was, to a degree, an effort to maintain peace on the European continent and was driven by the great European powers of the time, the Belgian revolution was unique in many aspects.

Few times in history has a revolution brought together such disparate viewpoints in favour of independence. Notably, the Belgian Revolution was not driven by a single ideology or social class.

Artist Charles Soubre depicts the arrival of Charles Rogier and the volunteers of Liège in Brussels to support the revolution.

Conservatives, liberals and radicals both campaigned and later fought side-by-side. It should also be recalled that the revolution occurred both in French-speaking and Dutch-speaking regions. Both regions fought for their linguistic rights against the backdrop of Dutch oppression. Nobles and elites from both the French- and Dutch-speaking communities fought for the creation of a Belgian nation, something often forgotten in centuries to come.

Related News

- How protests and rebellion created a nation in 1830

- Belgian Constitution turns 192 today: One of most liberal, but still little-known

Figures such as Charles Rogier, who led Liège volunteers to Brussels, and Louis de Potter, a radical journalist briefly at the helm of the new regime, helped shape the young state. Regent Surlet de Chokier steered the country in its transition before Leopold’s arrival, while King Leopold I would go on to rule for over three decades.

Although the revolution was limited in scale compared to other European uprisings, its outcome was significant. Belgium became the first country in the 19th century to successfully secede from a larger European power and win international recognition. It also birthed a nation, which at one point in the 19th century, was considered Europe’s second-largest economy.

Nearly 200 years later, the events of 1830 continue to influence Belgian political identity. The national day celebrations, more than just fireworks and festivities, should serve as a reminder of the united effort that created Belgium, liberated it from oppressors, and gave rise to the multilingual and historically rich state we live in today.