After 35 years as an expat in Brussels, I’d like to think of myself as a local. But I’m not. I never will be.

You get one chance to be a local. You stay in the place where you were born. You spend your life with the same people, share the same ideas, tell the same stories. I know people like that. But I left my home town in Scotland a long time ago. Even if I went back, I’d be someone who returned, not someone who belongs.

Back in 2016, soon after the United Kingdom had voted to leave the EU, prime minister Theresa May spoke at the Conservative Party conference against a rootless “international elite” who were the opposite of “the people down the road”. She didn’t stop there. “If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere — you don’t understand what citizenship means.”

It was a tough message for expats (not my favourite word, but I don’t have an alternative). Since you’re not from here, you’re not from anywhere. It’s an insult that expats have to accept. All through history, the person from out of town has been stigmatised.

'The people of Brussels decided they wanted expats'

And yet the expat community often brings fresh ideas, energy and investment to a place. One obvious example is Amsterdam where the Golden Age was fuelled by Flemish merchants and intellectuals fleeing from Antwerp along with Jews escaping European pogroms. And it hardly needs to be said that the United States was almost entirely settled by strangers from somewhere else.

Expats don’t receive a lot of love in Brussels. We’re criticised for many of the things that are wrong with the city. The high rents. The traffic. Almost everything can be blamed on foreigners. They will tell you Brussels was much better back in the 1950s when almost everyone was born here.

I would argue that the people of Brussels decided they wanted expats. Or at least they wanted the wealth that an expat community would bring. The city hosted Expo 58 with the aim of boosting the image of Brussels internationally. And Belgian politicians lobbied hard to attract international institutions like the European Commission and Nato.

In a 2017 book titled The Road to Somewhere, the British writer David Goodhart described the modern world as divided into two types of people – “the people from somewhere and the people from anywhere”. The somewhere people, according to Goodhart, are rooted in a particular place, whereas the anywhere people are global nomads who can easily adapt to different places.

An Anywhere might be born in Singapore, study in the United States, move to Germany for work and retire to Thailand. Whereas a Somewhere will never move from the place they were born. According to Goodhart, the Brexit vote and the Trump Revolution were both caused by the people from somewhere protesting at the people from anywhere.

The melting pot brings about change

Over the past 75 years, Brussels has changed because of the people from out of town. The city has a lively Congolese quarter in the Matonge and a distinct North African community along the Brussels to Charleroi canal. And of course there’s the EU Bubble in Ixelles where 27 nationalities come to work.

The result is that Brussels is now a city of multiple nationalities, languages and cultures. It would be a different place without the Moroccan market stalls, the South American restaurants and the African barber shops. But the expat community has possibly brought the biggest changes to Brussels.

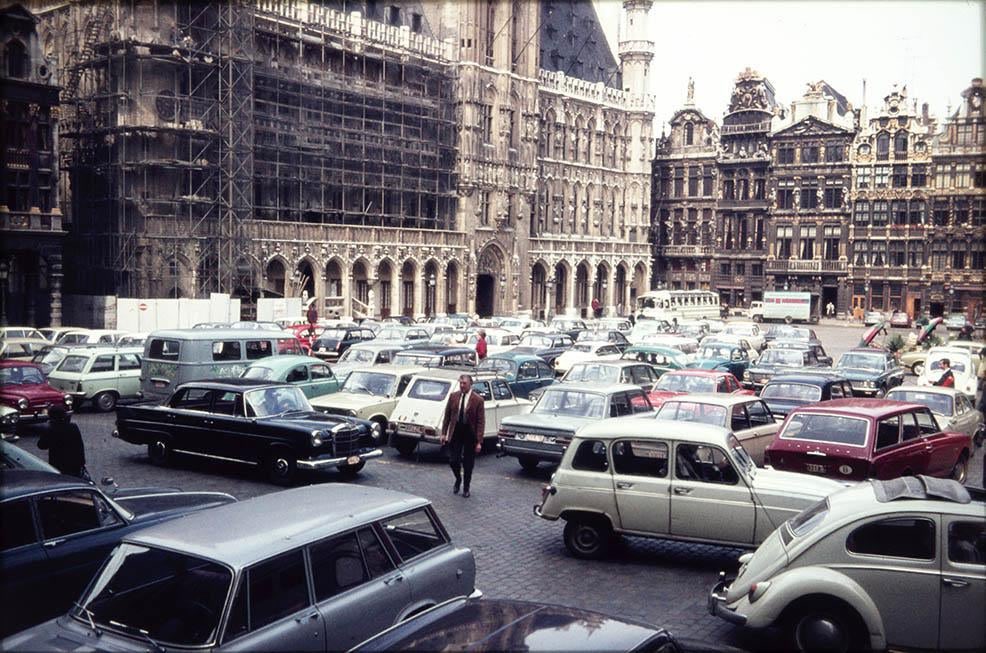

The expats delivered a seismic shock in the early 1970s when they called on the mayor to clear Grand Place of parked cars. Up until then, the beautiful baroque square served as “the most beautiful car park in the world,” according to one newspaper. The journalist John Lambert set off a campaign in 1971 during which protestors – mainly American and Canadian expats – held picnics on the square to block the traffic.

When Grand Place used to be a giant parking lot. Credit: Unknown.

The Brussels mayor Lucien Cooremans was initially furious at the foreigners. It took many months, and many more sit-downs, before he finally weighed up the arguments. His initial response was to stop cars parking on the square, although they could still drive through it. It was a typical Belgian compromise. It took until 1991 before the square was finally cleared of all cars.

Whither an authentic Brussels identity?

The Grand Place story reflects the way the city has slowly, and often reluctantly, listened to expats. Some people claim this has stripped the city of its authentic Brussels identity. The old bars with red neon signs and cheap Jupiler are replaced by Instagram-friendly coffee bars and brunch spots. The car drivers have to give way to urban cyclists. The meaty restaurants turn into vegan spots. Mostly, because that’s what expats want.

The expat population has grown over the years, making Brussels the most cosmopolitan city in the EU. Some 40 percent of the people who live here are foreigners. It’s hard to think of many other cities apart from London, Toronto or New York where you hear so many different languages spoken on the street or in the metro.

And yet it doesn’t feel to me as if this city of 180 languages has lost its identity. It has always been a cosmopolitan place that has attracted artists, writers, thinkers and exiles. It has a unique architecture that reflects almost every European style. The city’s cultural scene draws on every contemporary art trend you can imagine. Its cinemas show original-language films by every director on the planet. And the cafe culture has borrowed the best ideas from Amsterdam, Paris and London.

The bustling Place Luxembourg in the heart of the EU Quarter. Credit: Unknown.

You might want to argue that things would be better if the expats became rooted in the community. The Flemish government is trying to do this with its civic integration programme. It organises courses to encourage newcomers from outside the EU to understand Flemish culture and so fully contribute to society as a citizen, parent or employee.

It’s not a bad idea. Only it is only half the solution. The country should also make an effort to shape its institutions for the expats who have settled here. It can be a rather cold and unfriendly place to settle. A few years ago, after the Brexit vote, I acquired Belgian nationality. It felt like a step towards integration. “But you’re faux Belge – fake Belgian,” someone (a real Belgian) told me.

The challenges of integration

The gatekeepers of identity can be very harsh in Europe compared with other countries. I know a Spanish man who has lived for 30 years in Seville but locals still refuse to accept he is a Sevillano. A Parisian will spend a convivial lunch hour politely explaining why your accent gives away that you are not French.

In Belgium, integration is made worse by the language issue. Despite the growing expat population, the country is still governed by strict language laws laid down in the 1960s. The official languages are French and Dutch (along with German in the Eastern Cantons). Nothing else is allowed, even though the majority of expats are likely to speak English as a first or second language.

It makes it hard to start anything in Brussels aimed at expats. I learned this hard truth some years ago when I tried to get a grant to support a struggling English-language magazine. And again (after the magazine went bust), I wasted six months trying to launch an English-language radio station. The plan had to be abandoned because the broadcasting frequencies are divided between French and Dutch language stations.

All right, I agree we need to integrate. The mayor of Mechelen Bart Somers launched an inspiring plan back in 2000 when he took charge of the rather grey city of 86,000 people with roots in 120 different countries. His plan was to integrate everyone. “What counts is not your origin, but your future,” he argued.

Somers wrote a pamphlet with the title Iedereen Burgemeester! - Everyone for Mayor. He argued that citizens had to accept responsibility for their city, instead of just complaining. It worked. Mechelen was praised as a successful model for urban regeneration.

Mechelen has been praised as a model for urban regeneration. Credit: Frank.

In 2016, he was awarded the World Mayor Prize for transforming “the rather neglected city of Mechelen into one of Belgium’s most attractive places” as well as making it “a role model for integration.” Three years later, the Financial Times listed Mechelen as one of the top ten small European cities of the future.

Bart Somers wanted to turn people from nowhere into people from Mechelen. It didn’t matter that you weren’t born there, didn’t have roots in Mechelen. You just had to live in the city as a responsible citizen to belong there.

I’d love to live in Brussels as a responsible citizen. But, believe me, it’s not easy. Who do you call to talk about the endless unfinished construction sites, or the piles of dumped rubbish? How do you change the impossible road traffic? Who is going to listen to you when you have drug dealers operating outside your kids’ school. (Someone who recently complained to the police about drug gangs was advised to move to Flanders).

Dreaming of a better Brussels

We’ve been waiting for a Brussels regional government to be formed since we went to the polls as responsible citizens back in the summer of 2024. The failure to put together a working coalition means there is no one to make bold decisions that will shape the city’s future. This, I would argue, is a tragic failure of Belgium’s bilingual politics.

I am almost ready to suggest the city needs a new political party to serve the expat community, since no existing party takes account of our needs or opinions. The expat community is an incredible pool of talent from all over the world. There are experts who have the skills and ideas to make this city a better place. But they don’t have a voice in this bilingual city.

The hopelessness of Brussels politics is illustrated this summer by the absence of open air swimming in the city. In one of the most positive initiatives this year, Paris opened three swimming spots along the Seine. It’s now possible to swim in harbours and rivers in many European cities including Basel, Copenhagen, Stockholm and Oslo.

It could easily be done in Brussels. The city of Bruges has allowed swimming in one of the city’s mediaeval canals since 2019. I tried it out this year on the Coupure Canal close to the city centre. The stylish wooden structure has changing cabins, toilets and benches. It’s free for anyone to use without the fussy rules of an indoor pool.

I initially hesitated to jump into the murky canal water. But a notice at the entrance said the water was regularly tested. So in I plunged. The water is refreshingly cool like swimming in a Swedish lake. And you can sit around afterwards on a broad wooden deck and chat to the locals.

Meanwhile, the only open-air pool in the capital of Europe closed down at the end of May. Founded in 2021 by the citizens’ initiative Pool is Cool, Flow was designed to show the city authorities that open-air swimming was possible. But the city has so far showed little enthusiasm for the idea. It is starting to feel like we might be going back to the 1970s when the mayor just said no to any new initiative.

There have always been expats in Brussels who dream of living somewhere else. They would love it if the EU moved its capital to somewhere more attractive like Prague or Madrid or Stockholm. And many people do move on after two or three years.

As for me, I’m not planning to go anywhere. I’m prepared to stick it out in Brussels in the hope that things will get better. I might never become a local, but I’d like to think I’m not a citizen of nowhere.