Belgium and the Netherlands once formed a single country until Antwerp surrendered to the Spanish army in 1585, and shortly again in 1815 in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo. Recent declarations by Belgium’s prime minister suggest that reuniting the two countries should not be ruled out. But would this be possible?

Philosopher Philippe Van Parijs reflects on current debates in Brussels, Belgium and Europe

Only the most bizarre country can have a prime minister who publicly regrets its very existence. As previously reported by The Brussels Times, Belgium’s prime minister, Bart De Wever, took advantage of his presence in The Hague for the 24-25 June NATO summit to restate his affection for the idea of a “Groot-Nederland”, a Greater Netherlands.

In the visitors' book he signed during a dinner hosted by the Dutch king, he scribbled a quote from 19th-century Antwerp poet Theodoor van Ryswyck: “Here and there on the other side, there and here is the Netherlands.” And when interviewed by the Dutch TV channel NPO on 24 June, he restated his conviction that “the separation of the Netherlands in the 16th century is the greatest disaster that has ever befallen us.”

In an interview on the Flemish TV channel Kanaal Z in July 2021, on the occasion of Belgium’s national day, he had been somewhat more explicit: “A confederation of the Low Countries - the Seventeen Provinces - that could be rebuilt from the bottom up by working together in a practical way in many areas that bind us together. Yes, maybe that will become a reality the day after tomorrow. If I could die as a southern Nederlander, I would die happier than if I died as a Belgian.”

The fabulous 16th century

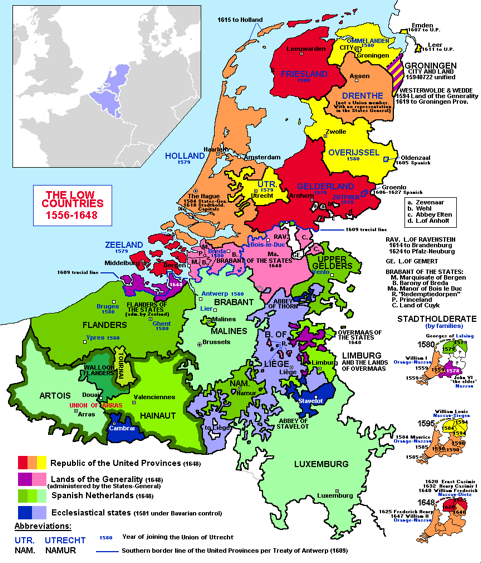

Note that the reunification evoked in both these statements is the restoration of the 16th-century Low Countries, the “Seventeen Provinces” that Charles V assembled in 1543. They included not only the territories of today’s Netherlands and Flanders, but also the County of Artois and the Western part of the County of Flanders (both part of today’s France), the Counties of Namur and Hainaut and the Duchies of Brabant and Luxembourg.

The Low Countries Map (1556-1648). Credit Wikimedia

William of Orange endeavoured to keep them all united in the rebellion against Spanish oppression. He was assassinated in 1584 after having to relocate the States General of the Low Countries (the predecessor of today’s Dutch Parliament) from Brussels to The Hague.

His lieutenant, Philippe de Marnix de Sainte-Aldegonde, attempted to defend Antwerp against a Spanish reconquest but was forced to surrender in 1585. He managed to negotiate the safety of the Antwerp population, but on one condition: its inhabitants were given five years to either convert back to Catholicism or leave the city.

The effect on the city itself was catastrophic. In 1585, with 80,000 inhabitants, Antwerp was Europe’s tenth most populous city, tied with Moscow and preceded only by Paris, London, Lisbon, Seville, and five Italian cities. Brussels, by contrast, had no more than 50.000 inhabitants, and Amsterdam about 35,000. Together with London, Antwerp was also by far the most important harbour in Northern Europe.

By 1589, however, Antwerp's population had shrunk to 41,000, and the Dutch Republic's blockade of the river Schelde led to a decline in its harbour, from which it only started recovering in the 19th century.

The rebirth of the “Seventeen Provinces”, however, cannot be more than a nostalgic dream. An attempt was made in 1815, but it came to an abrupt end 15 years later with the Belgian Revolution, which led to the creation of the Kingdom of Belgium and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

One cannot imagine that the 4.5 million Walloons and Luxembourgers will ever agree to being absorbed into a single country with 25 million Dutch speakers, let alone that France would give up three of its departments.

The closest one has ever been able to get, and will ever be able to get, to the realisation of that dream is the Benelux customs union established in 1948. It served as a model for the early stages of European integration but became largely irrelevant when the European Economic Community took off.

A less ambitious dream

Less fanciful perhaps is the more modest idea of reuniting the Dutch-speaking parts of the Seventeen Provinces: Flanders and the Netherlands. “Groot-Nederland” in this less ambitious sense featured in the programmes of several far-right parties when they were founded in the early 1930s: Verdinaso and VNV in Flanders, as well as the NSB in the Netherlands.

In a 2015 article, UGent history professor and brother of the current Belgian prime minister, Bruno De Wever, explained how these parties’ collaboration with the Nazis during World War II discredited the idea in the Flemish nationalist movement. He closes his article with a quote from his brother on Dutch television: “Whoever puts Groot-Nederland on the political agenda can forget about his political career”.

Evidence in support of this view is not hard to find. In the late 1990s, alderman Marc Van Peel, leader of Antwerp’s Christian-democrats, made the shocking remark that he would "even prefer to be stuck on a desert island with ten Moroccans than with two Dutchmen." He had to apologise to both the Moroccans and the Dutch, but the fact that he could let it slip is revealing enough of an attitude widely held in Flanders and further illustrated by the following anecdote.

In July 2018, I was invited to give a speech on the topic of my book, Belgium. Une utopie pour notre temps, at the graduation ceremony of the University of Antwerp’s Social Science Faculty. I presented the main conceivable scenarios for the splitting of Belgium and asked the hundreds of students and parents to shout “Ja” for the scenario they found most plausible (or least implausible).

When it was Groot-Nederland’s turn, the whole auditorium remained silent, except for a segment concentrated in one corner that shouted a very loud “Ja”. I asked rector Herman Van Goethem, sitting next to me, how this should be interpreted. “We have quite a few Dutch students” was the answer.

I shall never know whether these Dutch students and parents were a biased sample of the Dutch population with a special liking for Flanders, or simply a set of polite guests keen to express in this way their gratitude for Flemish hospitality. What is clear is that in Antwerp and elsewhere in Flanders (where I asked the same question), the Groot-Nederland scenario enjoys negligible support.

This did not prevent Bart De Wever from making his dream come true in his personal life, as he put it, by marrying a Dutch woman. Nor will it or should it prevent him (or me) from speculating about what could have happened had “we” not messed things up in the sixteenth century. If you read the chapters devoted to that period in his monumental Story of Antwerp (Het Verhaal van Antwerpen, 2024, 624p.), you will realise how great a potential was squandered as a result of failing to make timely compromises.

A lesson for the present? L’Union fait la force?