In February 2019, the largest ever preventive or rescue archaeological dig in the Brussels region began at the site of the demolished Parking 58 car park between the northern end of Boulevard Anspach and the church of Sainte Catherine.

Ancient documents showed archaeologists that this was the location of the original port of Brussels, arguably the birthplace of the city itself. The 1950s car park had replaced a vast covered market completed in 1874 as part of the scheme that buried the river Senne in the city centre.

The market in turn had replaced the river and a fish market from 1825 – and photographs of both exist. But whatever was underneath them had not been seen since 1604 when a first version of the fish market replaced the river port, rendered obsolete by the recently-opened canal. A very busy site then, but one for which definitive records did not exist.

The 6,000 square metre site in question was to be a new headquarters for the City of Brussels, the first time it had moved home since the construction of the historic Hôtel de Ville on the nearby Grand Place in the early 1400s.

Plans for the glassy and gigantic Brucity, completed in 2023, included an inversion of the previous situation, with even more parking but this time buried underground over four levels. As 20,000 tonnes of debris were cleared from the Parking 58 site, the foundations of the covered market emerged, brick vaults and thick cast-iron columns.

But that building descended just six metres, sufficient to erase its immediate predecessors. The car park for Brucity required an additional nine metres of excavation. The 50,000 cubic metres of material displaced yielded finds of such richness that the archaeologists won an additional two months of exclusive occupation of the site, making six in all.

They found not only the medieval quay but were able to sift through and analyse centuries’ worth of mud and sand layers coating the riverbed. From these, they extracted not only hundreds of once-cherished artefacts evoking everyday life in medieval Brussels but organic relics casting new light on how its citizens afforded these possessions.

The finds

The preliminary results of the dig were presented by one of the lead archaeologists in April 2025 at The Secrets of Underground Brussels, an event hosted by Urban, the regional agency responsible for urbanism, cultural heritage and urban renewal. As expected from a period when people routinely threw their trash in the river, finds included broken pots and worn-out poulaines (pointy medieval shoes) as well as valuables such as coins, perhaps lost when boarding or alighting from one of the boats also found broken up in the mud. Highlights included a valuable and unused 10th century millstone from the Eifel region of Germany, demonstrating the early reach of Brussels trade.

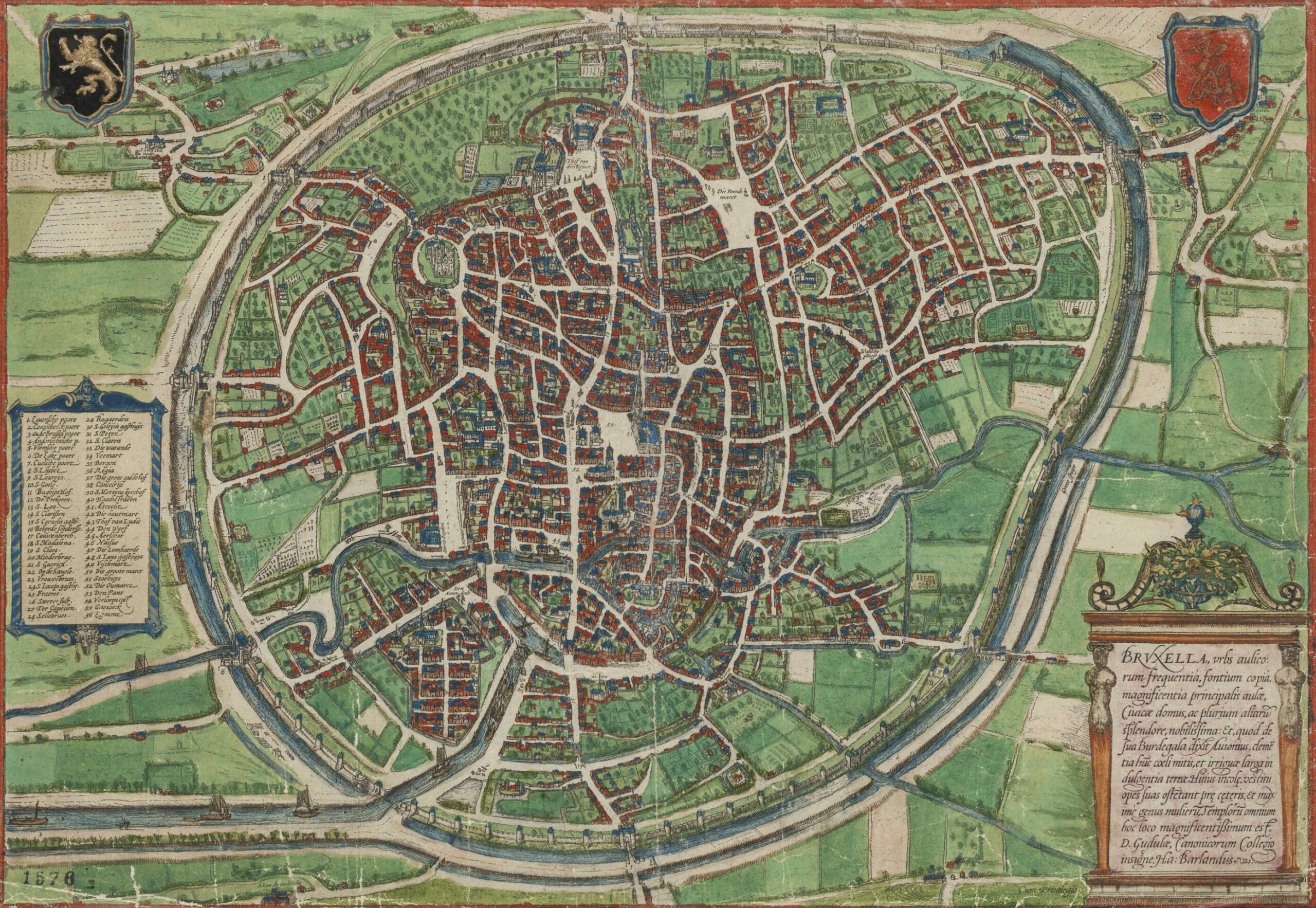

Old map of Brussels showing the Senne River's meandering route

Archaelogical excavation on the demolition site of former Parking 58 (Debrouckere) between Rue des Halles and Rue de la Vierge Noire, in Brussels city centre, Thursday 07 March 2019. Credit: Belga

The team found seven wicker traps for catching eels and carp, two of them complete and unique in Belgium, and a collection of 14th and 15th century pilgrimage badges, used by religious travellers to access hospitality and as proof of a penance purged. Of extreme rarity, two depict a local shrine (Notre-Dame de Grâce de Scheut in Anderlecht), perhaps evidence of passenger traffic on the Senne at a time when mills just upstream at present-day Saint-Géry were putting an end to navigation beyond the ever-expanding port. The novelty knick-knacks and cheeky humour Brussels is known for to this day emerged from the mud in the form of a little red cooking pot decorated with a phallus.

The logistics trade can be dull, especially when your cargo arrives on a sluggish, meandering river and people appear to have diverted themselves with dice and chess pieces made from bone, also pulled from the silt. Channels, weirs and diversions of the river upstream to harness its power for early industry slowed the flow further over the medieval period.

This encouraged deposits of lighter material to accumulate at the port alongside heavier relics. The archaeologists found cannon balls used as ballast to stabilise boats, and bomb fragments from the 1695 French attack on Brussels that destroyed thousands of houses, including almost all of the Grand Place.

The multi-disciplinary team has years of data and samples to sift through yet (they carried away 567 buckets of mud), but one intriguing find is a particularly high concentration of vine pollen detected in the mud, suggesting the possible presence of vineyards either nearby or just upstream. Brussels may need to revisit its image of an unbroken history as a beer city.

A fish-trap found during archaeological excavation on the demolition site of former Parking 58 (Debrouckere) between Rue des Halles and Rue de la Vierge Noire, in Brussels city centre, Thursday 07 March 2019. Credit: Belga

The most tangible discovery at the Brucity dig was the impressive stone quay laid bare in the middle of the site and visible to passers-by over the summer of 2019. This finally gave the archaeologists the chance to compare reality with the (not always reliable) historic maps, drawings and descriptions their trade had been obliged to rely on since the extinction of the final living memories of the ancient werf.

It appears to have been built in 12 phases between two bridges at the intersections of present-day Rue de la Vierge Noire with Rue de l’Évêque to the north and Rue du Marché aux Poulets to the south. No trace of the bridges was discovered (part of another bridge over the Senne further upstream is preserved in the basement of a hotel in Boulevard Anspach).

However, stairs and the impressive remains of a 23-metre-long loading ramp survived for analysis. We now know that masonry was held up with wooden piles driven into the soft riverbank and built in stages over increasingly sophisticated timber frames. As technology progressed, the structure was repeatedly improved and extended with patches and alterations over the operating lifetime of the werf (mid-13th to 16th centuries).

This make-do-and-mend approach is written into the city’s history as many much-altered structures can attest. Looking down, the stroller in Brussels can see 19th century cobbles and even tramlines peeping through worn layers of tarmac coating. Piled up high, these often raise the roadway above the neglected pavements, which can receive as much rainwater as the drains.

The region has adopted a new practice in recent years, which it calls the facade à facade renovation, sweeping away the lasagne of layers along with obsolete street furniture across the entire width of the street and starting anew (often with a reduction in or elimination of parking spaces and with additional vegetation to cool the environs and encourage rainwater run-off).

A tabula-rasa approach was also adopted at Brucity, where the authorities opted not to retain the quay, the cradle of the city, in place as a carpark feature, as has happened with key archaeological remains in other European cities. Seven large blocks of masonry were sawn off and carried away for further study but the archaeologists who excavated the port were the first to do so and will also be the last. At least now we have the photographs.

More surprises

Speaking at The Secrets of Underground Brussels, Ans Persoons, the region’s former Secretary of State for Urban Planning and Heritage, observed that the city’s hidden depths hold more surprises to follow the Brucity discoveries. “Archaeology is a very accessible approach to Brussels history, very physical and every time we open the ground people come to peer in the hole,” she said.

The authorities also know that the media are drawn to underground Brussels. New sinkholes in the capital pepper newspaper archives like costume changes for the Manneken Pis, and major infrastructure works bring the prospect of a private visit to the city’s hidden entrails, a delight to journalists through the ages.

Sainte-Catherine with water

In 1909, national daily Le Soir toured vast, forgotten galleries uncovered by works on the city’s second infrastructure priority in the 19th century after the Senne-covering scheme: taming the fearsome climb between the lower and upper towns. A vast and ancient quarter just below and to the west of the Park of Brussels was razed in preparation for the wide and car-friendly new curved street, Rue Courbe, which is now Rue Ravenstein. A ramp propped up on concrete piles, it traced an arabesque between the future Central Station site and Place Royale to deliver a gentler connection between the traffic networks of the downtown and the wealthy eastern suburbs.

The new road spanned the valley of a buried tributary of the Senne, the Coperbeek, and workers reportedly “floundered in filthy, liquid mud,” which had to be scooped out. At the bottom of the site, the project created cavernous new concrete spaces 6.5 metres tall under the roadway and a deep-set plot for the future Bozar cultural centre.

At its summit, the destruction of rue Isabelle, a 17th century access road between the ducal residence and the Collegiate church of Sainte Gudule, uncovered entrances to forgotten passages that had once led to the palace (destroyed by fire in 1731 and built over by Place Royale).

This was a homecoming gig of sorts for Le Soir, which was founded as a freesheet in Rue Isabelle in 1887. Its reporter was ushered, entranced, through a gallery preserving finely carved architectural details that led under Rue Royale to a spiral staircase beneath a grating in the pavement by the Hôtel de Belle-Vue (now BELvue museum). A scoop of sorts, as this route would form the backbone of the subterranean Coudenberg attraction, opened 91 years later in 2000. Today’s intriguing hole in the ground can be tomorrow’s top-flight tourist draw - but usually they are just resealed.

Mud crawler

In 1996, urban explorer (subtérranologue not speleologist, he insisted) Guy Deblock, President of the Société de recherche et d'étude des souterrains (Soberes) received the keys to the basement of the 1924 Justice Ministry on Boulevard de Waterloo next to the medieval gate Porte de Halle.

From there he accessed a passageway and shuffle, Shawshank-like, through the mud along a well-preserved stone gallery an astonishing 150 metres long. Professor Pierre-Paul Bonenfant, then lead archaeologist at the Coudenberg site, believed it served to prevent mines being placed beneath the long-vanished city ramparts above. It is yet to be included in the city's annual Heritage Days festival of unusual visits.

Fired up by the discovery, Bonenfant also speculated over the possibility of excavating major traces of the Monterrey Fort in Saint-Gilles, a Spanish-era (17th century) addition to the defences of Brussels which, like those of the city’s port until 2019, remain to this day in the realm of speculation and ancient documents. Only local street names recall its presence (Rue du Fort, Rue des Fortifications).

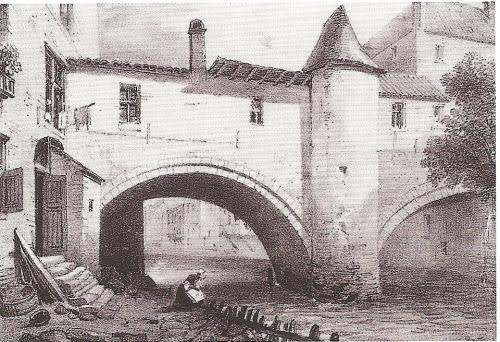

Brussels wall from 13th century passing over the Senne river. Today, a part of the arch can be found in the underground sauna of 159 Boulevard Anspach.

As Persoons said, underground Brussels may have more secrets in store. Le Soir’s 1909 report on the proto-Coudenberg attraction concluded with an enticing list of locations suspected of harbouring mysterious traces of the second city. Notable was an underground passage linking Rue des Alexiens with the ruins of the 11th to 12th century city Steenport Gate or Anneessens Tower, once much visited by the curious but whose entrance was walled up in the 1850s by a homeowner sick of urban explorers. Deblock tried to access it a century later. Whether he succeeded is a mystery perhaps resolved by a visit to the Bibliothèque du Patrimoine Souterrain, the library of underground heritage in Namur, which specialises in archiving these esoteric spaces as yet untapped for tourist potential.

Holes in the ground

Whether of human or natural origin, much of the complex landscape (and cityscape) met by visitors to the Brussels region two centuries ago has been filled in or papered over amid the process of creating the modern city and with it the secret spaces beneath. The 1820 guide, A New Picture of Brussels and its Environs by JB Romberg painted a picture of the city on the cusp of the Industrial Revolution, shortly before the process accelerated:

"Brussels is situated in a delightful valley, watered by the river Senne which crosses the city; it is surrounded by fertile heights which gently slope towards the river, and dividing themselves into small and irregular branches, form a romantic scene of hill and dale".

Excavations in Brussels

While that romantic scene may have been almost entirely eclipsed, its natural elements have been tamed rather than eliminated. The precipitous slope downtown from the park, which in 1820 was “very irregular and intersected with ravines,” has been disguised by the buildings and roads whose basements and foundations plunge many metres into the medieval street level but whose street-level avatars were scaled to give the illusion of an ordered succession of facades, demonstrating modernity’s capacity for the effortless domination of nature.

Likewise Ave Louise, where two kilometres of rolling countryside was levelled, infilled and bricked over to conjure up an ornate planted corridor of bourgeois order but where side streets straddle hidden gullies into which cellars can descend over three storeys.

As well as natural heritage, A New Picture of Brussels evokes a largely-forgotten past of human intervention, where in future suburbs quarries 20-30 metres deep fed the expanding downtown’s hunger for building material. In 2023 a resident in the south of Schaerbeek noticed a hole the size of a basketball hoop in his garden towards which the patio of the house next door was beginning to slide. With the insurance company, the local commune and the region unable to help, Xavier Devleeschouwer, an expert from the Geological Survey of Belgium, was called in and warned the hole could sit above a vast cavity.

Devleeschouwer knew this because exactly a century ago, engineers digging a railway tunnel here for the new line connecting Schaerbeek with Halle had to pause work after encountering a network of subterranean galleries. After penetrating a primaeval layer of marine silt containing oyster shells and shark teeth, they discovered an empty bottle and a bucket handle 21 metres below the surface and realised they weren’t the first humans down there.

The line had been routed through a worked-out quarry (for Lede stone, prized for its sculptability and used notably in the building of Brussels cathedral, three km away) of uncertain date and unmarked on any map. Le Soir was invited to visit the tunnel in December 1925 and dedicated two columns above the fold on the front page to assure the public that a new method using poured concrete instead of bricks would solve the challenge. Construction of the railway resumed without preserving records of the location of the quarries and, as Devleeschouwer put it: “We have no idea about their size, the direction they take or the height of these galleries.”

A hydrographical puzzle

Surprise quarries aside, the surface of the Brussels region is first and foremost a hydrographical puzzle traced by nature. It was waterways, now largely buried, not least the Senne itself, that first attracted humans to this zone. They irrigated crops (perhaps grapevines) and enabled their export in exchange for other goods, creating the need for a port.

Later, they would be harnessed to drive mills, notably along the Senne at Saint-Géry, where the river was dammed, diverted and manipulated to produce flour to feed the growing population and later to press cloth, an early value-added export.

Such interventions marked the beginning of urbanism in the region and the process of the city eating its own landscape, covering it in houses and streets. An expansion largely financed by demand for luxury goods sparked by the ancien régime court at Coudenberg.

The Marché aux Poissons

By the late 18th century, the no longer navigable part of the Senne upstream of Saint-Géry along present-day Boulevard Lemonnier and Ave de Stalingrad was given over to laundry… and leisure. The city’s first public baths opened in 1768 on Rue du Terre Neuve. Here, large gardens dotted with private bathing huts offered shaded walks along the Senne amid the wash houses.

The acceleration of technology soon brought factories (and pollution) to this quieter end of the city. A textile-dyeing plant opened on a riverside site near the present-day South Station/Gare de Midi. The arrival of steam power led to the creation of riverside indienneries (manufacturing printed cotton fabrics for export) along the future Ave de Stalingrad and then their replacement by the first Gare de Midi. It was located at present-day Place Rouppe until the 1860s and the unusually-wide avenue recalls its trackbed.

Micro-archaeology

Buried watercourses, hidden quarries and past uses such as those leaving polluted soil: these are ingredients for the complete data set developers need to attack a project with minimal risk. No such systematic, multi-layered, four-dimensional record exists as yet but one is under preparation.

The Secrets of Underground Brussels event continued with a presentation of the Archisols project (for Archives des Sols or ground archives). Funded by the region and working in partnership with academia and local authorities, the scheme brings together experts from pedologists to genealogists. The aim is to build an online platform assembling data scattered across state and local archives across the centuries, matching them up with resources such as old maps, historic building permits, family records and even human memory to create a plot-by-plot guide to constructability across the region.

As industry retreated from the Brussels region, to be replaced by roads, houses, offices and commerce, the process of smoothing out the cityscape accelerated. The ravines of 1820 have long since vanished but even in the postwar period, so too for example have the remaining inner-city branches of the Senne, disappearing under the expanding stone and concrete carapace of the modern city.

This process saw the impermeable surface of the region go from 26% of the total in 1955 to 53% by 2022, adding rainwater accumulation to any existing issues with low-lying sites. As Archisols’ coordinator Julie Goffaux explained, developers "often turn up with their permit in place, start digging and find something that delays work, bringing exorbitant costs.”

Remains of the mammoth are displayed inside Brussels-Midi station

In February 2022, the first alarms were sounded over the region’s flagship infrastructure project, the conversion of the subsurface tram line under the 19th century central boulevards into a full metro service. A notoriously tangled junction at the southern end meant the return of trains to Ave de Stalingrad but this time underneath, bypassing the bottleneck to create a wide straight tunnel for fast services.

The Brussels Times was invited underground to tour the works, where excavations had uncovered the spectacular remains of a mammoth which expired on the banks of the Senne at least 11,000 years ago (This is not the first time that mammoth bones were dug up during metro work: in the 1980s, 30,000-year-old fossils were found, which are now on display in a glass showcase in South Station’s lower level).

To connect this section to the existing route under the boulevard, an additional tunnel was planned under the historic Palais du Midi, built in the 1870s at the same time as the covered markets whose foundations emerged at the Brucity dig.

As at Schaerbeek a century earlier, the rail engineers hit an unexpected obstacle and had to rethink their technology. The elephant (or mammoth) in the room was the soil under the southern section of the Palais du Sud, built on a former bend of the Senne.

It was far wetter than test probes had appeared to suggest, too wet to sustain a conventional tunnelling technique. Instead, the Palais du Midi would be demolished leaving just the walls as a gesture to heritage and the tunnel’s structure would be inserted from above. The €700m budget for the central section of Metro Line 3 swelled to over €1.3bn.

Work on the Brussels Metro

With the planned northern extension of Line 3 to Bordet already mothballed, at the time of writing completion of the central section also appeared to be in doubt. A €477m loan for the project from the European Investment Bank was insufficient, given the state of the region’s finances, it was argued.

The outgoing Brussels Environment Minister Alain Maron called in May 2025 for a halt to work and to develop cheaper surface transport instead. The Federal Minister of the Interior Bernard Quintin (in charge of Beliris, the state agency for infrastructure improvements in Brussels) suggested a pause in the work lasting 5-10 years.

We have been here before. Work on the north-south metro line under the central boulevard of Brussels was already “paused” in the 1970s. As is obvious at the vast Bourse station, very long platforms were designed for full-scale metro services and “temporarily” shortened and lowered for pre-metro (tram) use to save costs.

A century ago, the forthcoming Schaerbeek line was designed to carry freight only, boosting passenger capacity on the western and eastern lines around the city. There were calls to scrap work on the useless indulgence of a north-south rail junction passing through the centre amid the crisis in public finances.

Risk-averse

While budget overruns are endemic in large urban infrastructure projects, arguments will persist over who is to blame for the miscalculation at the Palais du Midi. It is also clear that the Archisols project could grow into a powerful tool, lowering the risk and cost of development in Brussels, but not all of the risk.

Asked to comment on the fiasco of Line 3, Professor Devleeschouwer said: “We have data from 10,000 drillings throughout the Brussels region. That seems a lot, but in such a riverbed, with unpredictable deposits, that is actually very little. You often cannot really say what is between those drillings.”

At present, there is no mood to take risks in Brussels. In the absence of a functioning regional government to negotiate the fate of Line 3 with the Belgian state, economic life is paralysed and everyday life remains blighted in one of the poorest zones of the downtown, where traders on Ave de Stalingrad have operated out of stacked portacabins since the beginning of the decade.

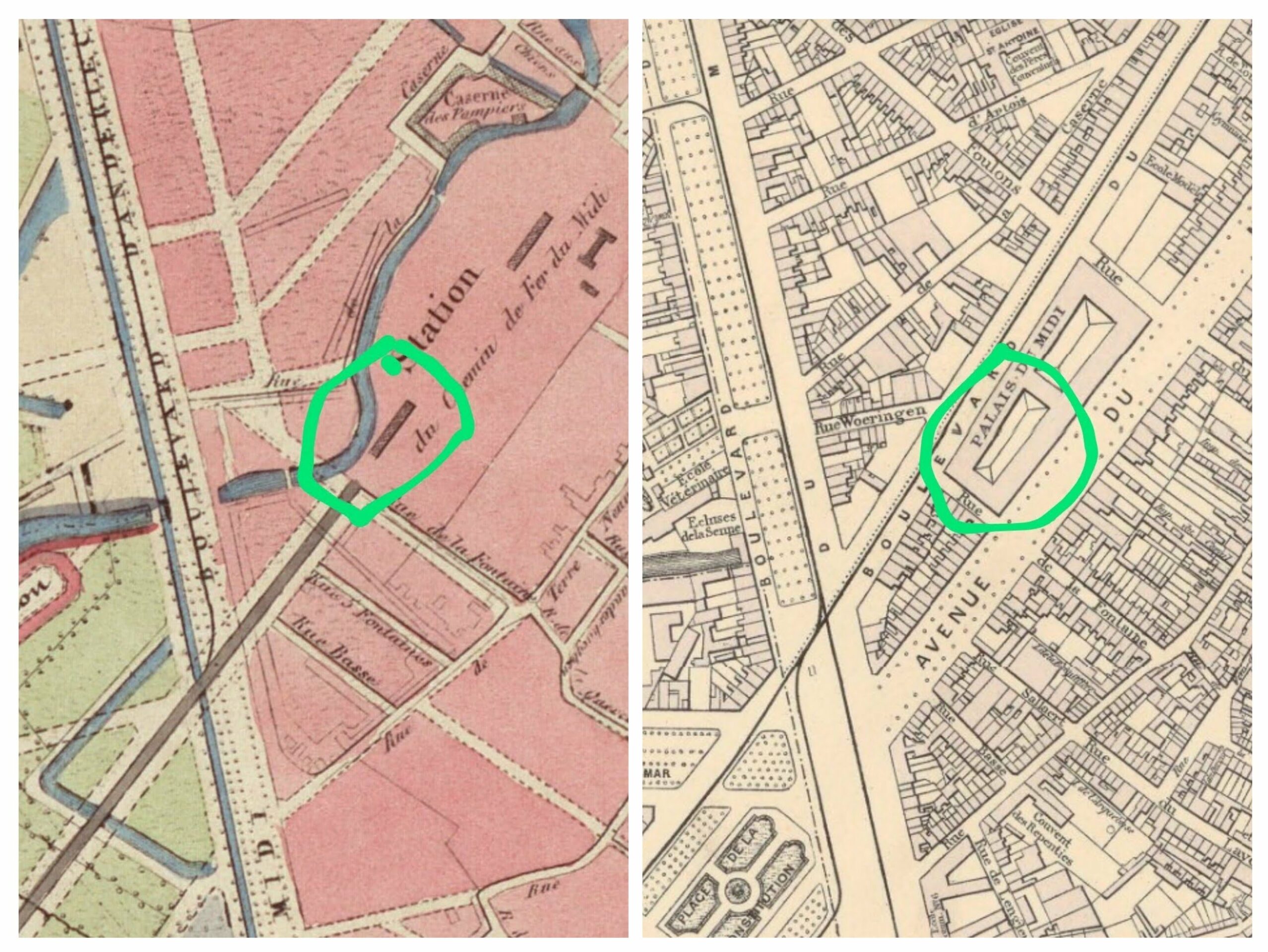

Left: Carte topographique des environs de Bruxelles, 1843. Charles Van der Straete. Detail from Bruxelles et ses environs, 1881 Institut cartographique militaire.

The transformations of central Brussels in the 1870s were also a great risk. Mired in corruption, plagued by indecision and marred by both overreach and under-ambition, they left a distinctly mixed legacy. While the modern sewer system was a triumph, the grand Paris-aping buildings were a failure, above all those of the covered markets.

Their demolition and replacement by the unloved Parking 58 and its subsequent demolition at least gave us a brief glimpse of the birthplace of the city. The success of the pedestrian zone however appears to offer the boulevards a second chance, encouraging suburbanites, day-trippers and visitors from abroad to re-engage with a previously blighted stretch of the centre.

Meanwhile, a quick decision is needed at the other end of the boulevard. Wags have suggested converting the orphaned tunnel at Stalingrad into a huge swimming pool. Perhaps it's time to take the risk, complete the planned Toots Thielemans station, spreading that renewed footfall to the south of the centre and move on to the glaring shortcomings of the South Station.

The fascinating discoveries at the excavations of the medieval port are a reminder that Brussels owes its origin and prosperity to activity driven by commerce and communications with its region and further afield and that perhaps its prospects also lie partly underground.